At a time of shrinking church membership, Jesus remains a uniquely powerful and popular figure in American culture. The great divide is over what he stands for.

By Francis X. Rocca – April 7, 2023 – The Wall Street Journal

My cmnt: I’ve edited this article for space. The entire article is linked to above.

My cmnt: I’m nearly 70-yrs- old and have lived thru and with all of the Jesus references in this article. I’ve been asked more than once which Jesus represents the true Jesus. And I have the answer for you. But first I must clarify which worldview I believe best corresponds to reality.

My cmnt: There are presently only two dominate worldviews at large in the Western world. They are materialism (also known as naturalism) and super-naturalism (or supra-naturalism). Materialists hold that at bottom, the universe is a chance dance of particles under certain physical laws and that given enough time, or universes, any and everything can and will happen sooner or later. This view holds that information can arise by chance and from the strictly material. Values are man-made and less important than any material possession. Hence strict materialists upon realizing that life has no meaning and man is the product of mindless, directionless material causes often kill themselves rather than carry on to a meaningless conclusion.

My cmnt: Super-naturalists hold that information always and only comes from an intelligent agent. They maintain that in our actual experience this is always and invariably true. They hold that at bottom, the universe is information from the mind of God. The physical laws which govern the behavior of particles are themselves supernatural and have no material substance. Life, particularly the living cell, is a mysterious code book written in DNA and the most complex form of information known to man. Values are the most important things man can possess. They are intangible (i.e., not material) and the big six are Faith, Hope and Love followed by Beauty, Goodness and Truth. Without these values life is not worth living and indeed many a materialist, including Nietzsche, have recognized such and despaired of living.

My cmnt: Therefore if materialism best reflects reality then Jesus is simply another material entity espousing platitudes which may or may not be helpful in the struggle to survive and reproduce. In as far as religion operates as the opium of the people it may be useful for the ruling elite to use it to control the masses.

My cmnt: If however supernaturalism best reflects reality and therefore God likely exists, then Jesus, being demonstrated to be from God by His miracles, and more especially to be God by His rising from the dead – then His words and teachings are both Truth and the path to Life – and more importantly, faith in Him is eternal life and all material things of this universe are secondary to that. And as a corollary to that arguing over what exactly Jesus taught is less important than trusting in Him as your Savior. Also His Church has interpreted His teachings for us in the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds as authoritative and universal understandings of who He is and what we are to believe about Him. All other disputes about His teachings, while important, are secondary (and likely Tertiary) to that.

Easter is the peak time for searching for “Jesus,” according to the Google Trends website, which measures the popularity of online queries. But this February, interest ran higher than at any other time of year including Christmas. The reason seems to have been a pair of unusual ads that ran during the Super Bowl telecast.

Both were almost exclusively montages of black-and-white still photographs, with musical soundtracks and no narration. One featured children showing kindness to each other or to animals, as Patsy Cline sang about seeing the world through the eyes of a child. The other, in sharp contrast, showed Americans confronting each other angrily, and in some cases violently, to the accompaniment of Rag’n’Bone Man’s plaintive and pounding song “Human,” mingled with sounds of shouting and a siren.

The message of each was explicit only in written words at the end: “Jesus didn’t want us to act like adults” for the first one and “Jesus loved the people we hate” for the second. Both ended with the slogan: “He Gets Us. All of Us.”

The ads are part of a series that started on TV and online the previous March and will continue to run, with new installments, at least until March 2025. The He Gets Us campaign says it plans to spend a billion dollars on its efforts, including broadcasts, paid partnerships with professional sports teams and the distribution of T-shirts and other gear. An associated website offers Bible-reading programs, a number to send prayer requests by text message and the opportunity to connect to a local Protestant or Catholic church.

R. Albert Mohler Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, told listeners of his podcast, “When we talk about persons actually coming to faith in Christ, it actually takes the clear presentation of the Gospel itself. They have to be told about their sin, and all must be told about Christ and his death on the cross and his resurrection from the dead.”

“We believe [Jesus] was fully God and fully man,” the campaign said in a statement. “Our media messages focus on his humanity—since we’ve learned these resonate with the widest possible audience. Then, we extend an open invitation to engage and learn more.”

Nothing better reflects the social divisions targeted by He Gets Us than the competing and sometimes clashing versions of Jesus espoused by different parts of American society today.

Variety in portrayals of Jesus is practically as old as Christianity itself, starting with the four accounts of his life presented in the Bible. “The different Gospels give you different versions of Jesus,” said Amy-Jill Levine, a professor of New Testament and Jewish Studies at Hartford International University for Religion and Peace. “We put them together…for ourselves, because no one’s Jesus is going to be like someone else’s Jesus.”

Some portrayals remain emblematic of their epoch. Thomas Jefferson crafted a rational Jesus for the Age of Enlightenment by producing a version of the Gospels with the miracles and most supernatural references left out. Philip Jenkins, a professor of history at Baylor University, notes that the 1960s produced both the subversive Jesus of the Catholic theology of liberation, which emphasizes solidarity with the poor and the need to challenge socioeconomic structures of sin, and the “Jesus movement,” which blended charismatic practices harking back to early Christianity with the countercultural lifestyle of the hippies.

The Jesus of He Gets Us is a countercultural figure. One video describes him as a rebel who “took to the streets…roamed the hood and challenged authority.” In another, he is “an influencer” who ends up getting “canceled” for his views. But he is above all a welcoming presence, who “prepared a feast and invited all into his home.”

The Rev. James Martin, a Catholic priest in New York who heads a ministry for LGBTQ Catholics, says that he focuses on the side of Jesus in the Gospels who “reaches out to those on the margins,” such as a notorious tax collector or a woman who has been married five times.

Pope Francis, who famously asked “Who am I to judge?” in response to a question about gay priests, likewise emphasizes the welcoming side of Jesus, says R.R. Reno, editor of the conservative religious journal First Things. Modern culture, Mr. Reno says, is less receptive to the demanding Jesus of scripture, who tells his followers, “If your right eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away,” and who sternly forbids divorce.

The contrast between the welcoming Jesus and the demanding Jesus parallels in some ways that between a Jesus who calls for social justice and one who calls for repentance and personal conversion.

The controversial psychologist and author Jordan Peterson recently suggested a stark opposition between the two, in response to a tweet by Pope Francis calling for efforts to combat inequality and support the rights of labor. “There is nothing Christian about #SocialJustice. Redemptive salvation is a matter of the individual soul,” Mr. Peterson tweeted back at the pope.

Richard Flory, a sociologist at the University of Southern California, points to a more subtle difference in emphasis among the evangelical Christian pastors and congregants he has interviewed over the last three decades. He distinguishes two groups, based on which version of the beatitudes—the blessings recounted by Jesus in two of the Gospels—they prefer to cite.

Evangelicals who quote the version in the Gospel of St. Luke, which includes the words “Blessed are you who are poor…but woe to you who are rich,” tend to stress broad inclusion in the church as well as a commitment to social justice, Mr. Flory says. Those who cite the version in the Gospel of St. Matthew—where the equivalent verse reads “Blessed are the poor in spirit”—typically emphasize the need for personal faith and moral conduct. The latter group, he says, is much more numerous.

“What has been happening in American Christianity is that morality has been placed first,” says Jason Vanderground, a spokesman for He Gets Us, explaining that the campaign has sought a less divisive approach by focusing on Jesus’ demonstrations of unconditional love.

Peter Wehner, who served in three Republican presidential administrations and is now a senior fellow at the Trinity Forum, a Christian think tank in Washington, D.C., says that a call to Jesus that stresses moral demands has lost credibility in recent years. He points to scandals over sexual abuse and sexual misconduct in Catholic and Protestant institutions and the support of some Christian leaders for former President Donald Trump.

Another version of Jesus that clashes with more common representations is that of the warrior, based not on the Gospels but on the Book of Revelation, which describes Christ returning to earth astride a white horse at the end of the world: “His eyes are like blazing fire…He is dressed in a robe dipped in blood…Coming out of his mouth is a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations.”

Warrior Jesus was a frequent subject of popular art in the period of the apocalyptic “Left Behind” novels, bestsellers published between 1995 and 2007. According to Mr. Hudnut-Beumler, warrior Jesus has gone largely out of fashion in recent years, in part because of weariness with the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Kristin Du Mez, a professor of history at Calvin University and author of “Jesus and John Wayne,” a study of conservative evangelicals, says that many who once looked to warrior Jesus as an emblem of their side in the culture wars have replaced him in that role with Mr. Trump.

On the other hand, Jesus as a victim of oppression remains a prominent subject for artists. Though none of the He Gets Us videos features a direct visual representation of Jesus, some follow in this victim tradition, including a video that identifies him with Guatemalan refugees fleeing violence in their country.

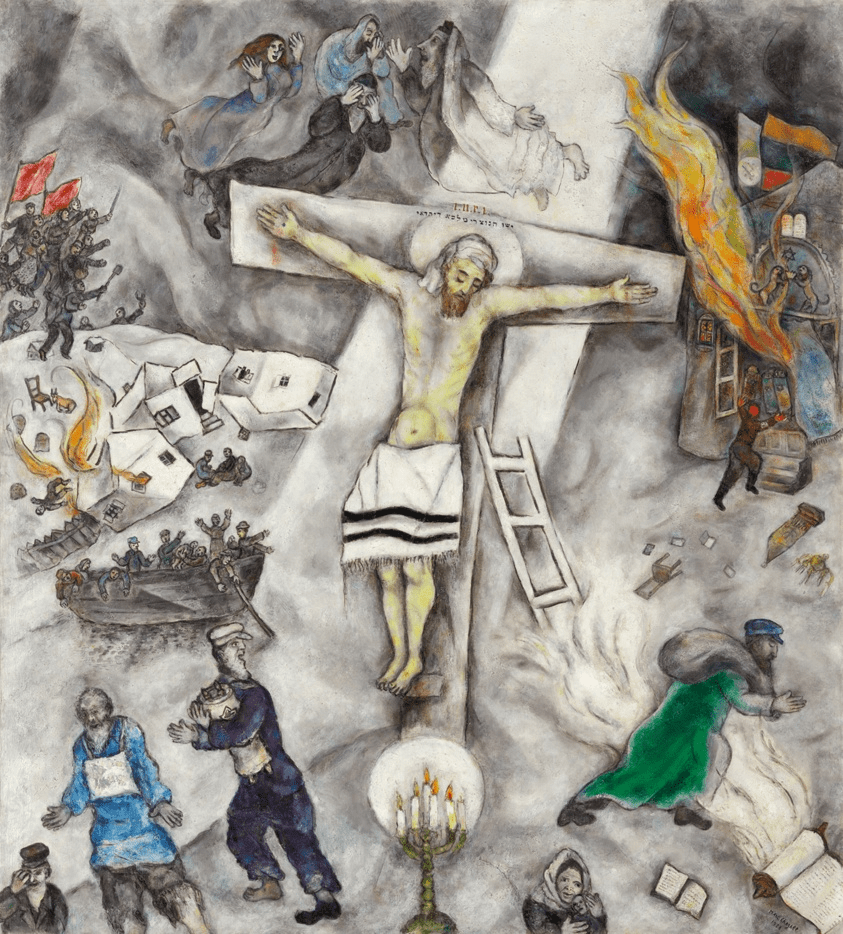

An early example of such portrayals, according to Elizabeth Lev, an art historian based in Rome, is Marc Chagall’s 1938 painting “White Crucifixion,” which shows Jesus as a Jew wearing a traditional prayer shawl in lieu of a loincloth. He is flanked by scenes of antisemitic persecution, recalling pogroms during the artist’s boyhood in the Russian Empire as well as more recent events in Nazi Germany. Pope Francis has called it one of his favorite paintings.

An especially controversial recent example of the genre is “Mama,” an image by the iconographer Kelly Latimore portraying the dead Jesus with a face resembling that of George Floyd. By contrast, the face of the life-size bronze sculpture “Homeless Jesus”—casts of which have been installed in over 100 locations, including the Vatican—is invisible. He lies on a park bench beneath a blanket shrouding almost all of his body. Only when viewers get close enough to see the wounds of the crucifixion on the exposed feet do they recognize the subject. The sculptor, Timothy Schmalz, says he considered showing Jesus’ face but concluded that leaving it to everyone’s imagination was a more fitting solution for a multicultural society.

Images of Jesus as a Black man have been increasingly common since the civil rights movement, yet the question of his race remains controversial. In 2020, the activist Shaun King tweeted a call for the removal of “all murals and stained glass windows of white Jesus,” which he called “a gross form [of] white supremacy. Created as tools of oppression. Racist propaganda.”

For Christian Smith, a professor of sociology at Notre Dame, the proliferation of rival ideas of what Jesus stands for undermines the cultural authority of them all, by feeding into the “pluralistic, subjectivistic, relativistic” understanding of religion that prevails in contemporary America. “The fact that there’s just so many different voices says, ‘How can you possibly know or choose?’” he says. “You just pick whatever appeals or doesn’t appeal to you.”

Some believe that the transcendent Christian significance of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection nevertheless shines through even a partial statement of his teaching.

“Forgiveness and love of your enemies is a sacrificial act,” says Mr. Reno, speaking of the He Gets Us ad on the topic. “It’s an act that compensates for the fallenness of the human condition.”

“I could require an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth but instead, in forgiveness, my generosity compensates for the brokenness of human relations,” he says. “And Jesus plays that role, obviously at a cosmic level, and his sacrifice on the cross is an atonement for the sins of the entire world.”

Francis Bacon talks about this situation in Idols of the Mind.

LikeLike