Feb. 9, 2026 – New York Times – Editorial Board

Thirteen years ago, no state allowed marijuana for recreational purposes. Today, most Americans live in a state that allows them to buy and smoke a joint. President Trump continued the trend toward legalization in December by loosening federal restrictions.

This editorial board has long supported marijuana legalization. In 2014, we published a six-part series that compared the federal marijuana ban to alcohol prohibition and argued for repeal. Much of what we wrote then holds up — but not all of it does.

At the time, supporters of legalization predicted that it would bring few downsides. In our editorials, we described marijuana addiction and dependence as “relatively minor problems.” Many advocates went further and claimed that marijuana was a harmless drug that might even bring net health benefits. They also said that legalization might not lead to greater use.

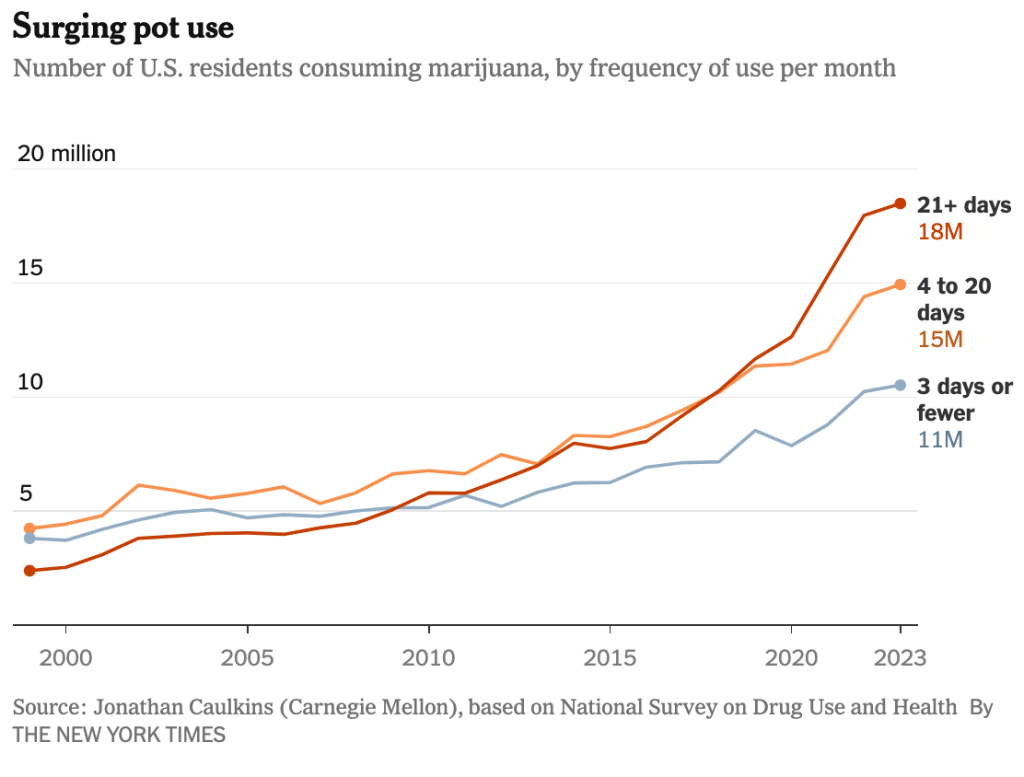

It is now clear that many of these predictions were wrong. Legalization has led to much more use. Surveys suggest that about 18 million people in the United States have used marijuana almost daily (or about five times a week) in recent years. That was up from around six million in 2012 and less than one million in 1992. More Americans now use marijuana daily than alcohol.

This wider use has caused a rise in addiction and other problems. Each year, nearly 2.8 million people in the United States suffer from cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, which causes severe vomiting and stomach pain. More people have also ended up in hospitals with marijuana-linked paranoia and chronic psychotic disorders. Bystanders have also been hurt, including by people driving under the influence of pot.

America should not go back to prohibition to fix these problems. The war on marijuana brought its own costs. Every year, authorities arrested hundreds of thousands of Americans for marijuana possession. The people who suffered the legal and financial consequences were disproportionately Black, Latino and poor. A society that allows adults to use alcohol and tobacco cannot sensibly arrest people for marijuana use. We oppose the nascent efforts to re-criminalize the drug, such as a potential ballot initiative in Massachusetts this year that would ban recreational sales and home growing.

Yet there is a lot of space between heavy-handed criminal prohibition and hands-off commercial legalization. Much as the United States previously went too far in banning pot, it has recently gone too far in accepting and even promoting its use. Given the growing harms from marijuana use, American lawmakers should do more to regulate it. The most promising approach is one popularized by Mark Kleiman, a drug policy scholar who died in 2019. He described it as “grudging toleration.” Governments can enact policies that keep the drug legal and try to curb its biggest downsides. Culture and social norms can play an important role, too.

The larger point is that a society should be willing to examine the real-world impact of any major policy change and consider additional changes in response to new facts. In the case of marijuana, the recent evidence offers reason for Americans to become more grudging about accepting its use.

Editors’ Picks

24 Easy Valentine’s Day Recipes That Anyone Can MakeThis George Washington Cherry Story Is Actually TrueSurf Shacks and Ocean Breezes: Welcome to Riviera Nayarit

Over the past several decades, supporters of marijuana legalization often called for a strategy of “legalize and regulate.” It is a smart approach. Unfortunately, the country has pursued the first part of it while largely ignoring the second.

We want to emphasize that occasional marijuana use is no more a problem than drinking a glass of wine with dinner or smoking a celebratory cigar. Many Americans find it enjoyable to smoke a joint or eat an edible, with friends or alone. Some people with serious illnesses have found relief with marijuana. Adults should have the freedom to use it.

Still, any product that brings both pleasures and problems requires a balancing act, and marijuana falls into this category. Yes, it is safer than alcohol and tobacco in some ways, but it is not harmless. The biggest concern is excessive use. At least one in 10 people who use marijuana develops an addiction, a similar share as with alcohol. Even some who do not develop an addiction can still use it too much. People who are frequently stoned can struggle to hold a job or take care of their families. “As marijuana legalization has accelerated across the country, doctors are contending with the effects of an explosion in the use of the drug and its intensity,” a New York Times investigation concluded in 2024. “The accumulating harm is broader and more severe than previously reported.”

Jennifer Macaluso, a hairdresser in Illinois, experienced these harms. She turned to marijuana to treat severe migraines, and the drug helped at first. After months of use, though, she started getting sick. Her nausea and vomiting became so bad that she had to stop working. Only after months of seeing doctors did one finally confirm marijuana was the problem. “Why don’t more doctors know about it?” she told The Times. “Why didn’t anyone ever mention it to me?”

Part of the answer is the power of Big Weed. For-profit marijuana companies, made possible by legalization, have a financial incentive to mislead the public about what they are selling. Marijuana and CBD companies have made false claims that their products can treat cancer and Alzheimer’s. Others have sold products, such as “Trips Ahoy” and “Double Stuf Stoneo,” in packages that mimic snacks for children. The companies’ executives know they can increase profits by downplaying the harms of frequent use: More than half of industry sales come from the roughly 20 percent of customers known as heavy users.

The legal pot industry grew to more than $30 billion in U.S. sales in 2024, close to the total annual revenue of Starbucks. As the industry has grown, it has increased lobbying of state and federal lawmakers, and it has won some big victories. Marijuana companies, not casual smokers, are the biggest winners of Mr. Trump’s decision to reclassify the drug from Schedule I to Schedule III. The change will increase the profits of these businesses by causing the tax code to treat them more favorably. This does not qualify as grudging toleration.

A better approach would acknowledge that many people end up worse off when they start to use marijuana more frequently. The goal should not be elimination. It should be to slow the recent rise, and perhaps partly reverse it, while acknowledging that many people use marijuana safely and responsibly. Alcohol and tobacco offer a useful framework. Both are legal with limitations, including relatively high taxes, open-container laws and regulations on alcohol and nicotine levels. The goal is to balance personal freedom and public health.

Marijuana, however, is less regulated in several crucial ways. The federal government taxes alcohol and tobacco, for example, but not marijuana. And increases in tobacco taxes have been a major reason that its use has declined during the 21st century, with profound health benefits.

The first step in a strategy to reduce marijuana abuse should be a federal tax on pot. States should also raise taxes on pot; today, state taxes can be as low as a few additional cents on a joint. Taxes should be high enough to deter excessive use, on the scale of dollars per joint, not cents. (Federal alcohol taxes, which have failed to keep pace with inflation since the 1990s, should rise, too.)

An advantage of taxes is that they fall much more on heavy users than casual smokers. If a joint cost $10 instead of $5, it would mean a lot of extra money for someone now smoking multiple joints a day and may change that person’s behavior. It would not be a big burden for someone who smokes occasionally.

A second step should be restrictions on the most harmful forms of marijuana, which would also be similar to regulations for alcohol and tobacco. Today’s cannabis is far more potent than the pot that preceded legalization. In 1995, the marijuana seized by the Drug Enforcement Administration was around 4 percent THC, the primary psychoactive compound in pot. Today, you can buy marijuana products with THC levels of 90 percent or more. As the cliché goes, this is not your parents’ weed. It is as if some beer brands were still sold as beer but contained as much alcohol per ounce as whiskey.

Not surprisingly, greater THC potency has contributed to more addiction and illness. The appropriate response is both to make illegal any marijuana product that exceeds a THC level of 60 percent and to impose higher taxes on potent forms of pot, much as liquor is taxed more heavily than beer and wine.

Third, the federal government should take action on medical marijuana. Decades of studies on the drug have proved disappointing to its boosters, finding little medical benefit. Yet many dispensaries claim, without evidence, that marijuana treats a host of medical conditions. The government should crack down on these outlandish claims. It should issue a clear warning to dispensaries that falsely promise cures and then close those that do not comply.

The federal government needs to be part of these solutions. Leaving taxes and regulations to the states threatens to create a race to the bottom in which people can cross state lines to buy their pot. Congress can set a floor, as it has done, however inadequately, with alcohol and tobacco, and states can build on it as they choose.

The unfortunate truth is that the loosening of marijuana policies — especially the decision to legalize pot without adequately regulating it — has led to worse outcomes than many Americans expected. It is time to acknowledge reality and change course.

Legalizing Marijuana Is a Big Mistake

May 17, 2023 – The New York Times

By Ross Douthat

Opinion Columnist

Of all the ways to win a culture war, the smoothest is to just make the other side seem hopelessly uncool. So it’s been with the march of marijuana legalization: There have been moral arguments about the excesses of the drug war and medical arguments about the potential benefits of pot, but the vibe of the whole debate has pitted the chill against the uptight, the cool against the square, the relaxed future against the Principal Skinners of the past.

As support for legalization has climbed, commanding a two-thirds majority in recent polling, any contrary argument has come to feel a bit futile, and even modest cavils are couched in an apologetic and defensive style. Of course I don’t question the right to get high, but perhaps the pervasive smell of weed in our cities is a bit unfortunate …? I’m not a narc or anything, but maybe New York City doesn’t need quite so many unlicensed pot dealers …?

All of this means that it will take a long time for conventional wisdom to acknowledge the truth that seems readily apparent to squares like me: Marijuana legalization as we’ve done it so far has been a policy failure, a potential social disaster, a clear and evident mistake.

The best version of the square’s case is an essay by Charles Fain Lehman of the Manhattan Institute explaining his evolution from youthful libertarian to grown-up prohibitionist. It will not convince readers who come in with stringently libertarian presuppositions — who believe on high principle that consenting adults should be able to purchase, sell and enjoy almost any substance short of fentanyl and that no second-order social consequence can justify infringing on this right.

But Lehman explains in detail why the second-order effects of marijuana legalization have mostly vindicated the pessimists and skeptics. First, on the criminal justice front, the expectation that legalizing pot would help reduce America’s prison population by clearing out nonviolent offenders was always overdrawn, since marijuana convictions made up a small share of the incarceration rate even at its height. But Lehman argues that there is also no good evidence so far that legalization reduces racially discriminatory patterns of policing and arrests. In his view, cops often use marijuana as a pretext to search someone they suspect of a more serious crime, and they simply substitute some other pretext when the law changes, leaving arrest rates basically unchanged.

Sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter Get expert analysis of the news and a guide to the big ideas shaping the world every weekday morning. Get it sent to your inbox.

So legalization isn’t necessarily striking a great blow against mass incarceration or for racial justice. Nor is it doing great things for public health. There was hope, and some early evidence, that legal pot might substitute for opioid use, but some of the more recent data cuts the other way: A new paper published in The Journal of Health Economics found that “legal medical marijuana, particularly when available through retail dispensaries, is associated with higher opioid mortality.” There are therapeutic benefits to cannabis that justify its availability for prescription, but the evidence of its risks keeps increasing: This month brought a new paper strengthening the link between heavy pot use and the onset of schizophrenia in young men.

And the broad downside risks of marijuana, beyond extreme dangers like schizophrenia, remain as evident as ever: a form of personal degradation, of lost attention and performance and motivation, that isn’t mortally dangerous in the way of heroin but that can damage or derail an awful lot of human lives. Most casual pot smokers won’t have this experience, but the legalization era has seen a sharp increase in the number of noncasual users. Occasional use has risen substantially since 2008, but daily or near-daily use is up much more, with around 16 million Americans, out of more than 50 million users, now suffering from what is termed marijuana use disorder.

In theory, there are technocratic responses to these unfortunate trends. In its ideal form, legalization would be accompanied by effective regulation and taxation, and as Lehman notes, on paper it should be possible to discourage addiction by raising taxes in the legal market, effectively nudging users toward more casual consumption.

In practice, it hasn’t worked that way. Because of all the years of prohibition, a mature and supple illegal marketplace already exists, ready to undercut whatever prices the legal market charges. So to make the legal marketplace successful and amenable to regulation, you would probably need much more enforcement against the illegal marketplace — which is difficult and expensive and, again, obviously uncool, in conflict with the good-vibrations spirit of the legalizers.

Then you have the extreme case of New York, where legal permitting has lagged while untold numbers of illegal shops are doing business unmolested by the police. But even in less-incompetent-seeming states and localities, a similar pattern persists. Lehman cites (and has reviewed) the recent book “Can Legal Weed Win? The Blunt Realities of Cannabis Economics,” by Robin Goldstein and Daniel Sumner, which shows that unlicensed weed can cost as much as 50 percent less than the licensed variety. So the more you tax and regulate legal pot sales, the more you run the risk of having users just switch to the black market — and if you want the licensed market to crowd out the black market instead, you probably need to make legal pot as cheap as possible, which in turn undermines any effort to discourage chronic, life-altering abuse.

Thus policymakers who don’t want so much chronic use and personal degradation have two options. They can set out to design a much more effective (but necessarily expensive, complex and sometimes punitive) system of regulation and enforcement than what exists so far. Or they can reach for the blunt instrument of recriminalization, which Lehman prefers for its simplicity — with medical exceptions still carved out and with the possibility that possession could remain legal and that only production and distribution be prohibited.

I expect legalization to advance much further before either of these alternatives builds significant support. But eventually the culture will recognize that under the banner of personal choice, we’re running a general experiment in exploitation — addicting our more vulnerable neighbors to myriad pleasant-seeming vices, handing our children over to the social media dopamine machine and spreading degradation wherever casinos spring up and weed shops flourish.

With that realization, and only with that realization, will the squares get the hearing they deserve.

Leave a comment