The legendary magazine editor died Tuesday night at 95. In his final published words, he reflects on a life well lived.

By Norman Podhoretz – The Free Press – 12.17.25 — The Big Read

On Wednesday morning, we woke up to the news that legendary magazine editor Norman Podhoretz had died peacefully in Manhattan. He was 95. Podhoretz, who edited Commentary magazine between 1960 and 1995, was renowned as one of the great giants of neoconservatism—an irrepressible intellectual force in American public life.

Several months ago, I had the honor of meeting Norman, to interview him for a piece in The Free Press, which we’re reprinting below. For two and a half hours, we sat together in his apartment in Manhattan. Bookshelves lined the walls, crammed with hundreds upon hundreds of titles. In the entryway hung the Presidential Medal of Freedom given to him in 2004 by President George W. Bush.

Age had chipped away at his ease of movement and speaking, but he resisted it. On the coffee table sat a photograph of Norman at about 22 years old. “I think that’s what I look like,” he confessed to me. Coursing through his words was a fierce sense of loyalty to his character, to his family, and to his country. “I’m a rabid American patriot,” he told me. He took immense pride in his career and legacy—which now includes 13 grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren.

“I’ve lived a rich life, in every sense,” reads the following piece, drawn from our conversation. In it, he recounts his remarkable journey: One that began in the slums of Brownsville, Brooklyn, and ended in the heart of what he describes as the “glittering fortress of class and intellect” that is Manhattan.

I’ll forever treasure the time I spent with Norman before his passing. Here’s what he told me about his extraordinary life. May his memory be a blessing. —Jillian Lederman

“One of the longest journeys in the world is the journey from Brooklyn to Manhattan.”

I wrote that line in 1967, and for better or worse, it has been quoted back to me ever since. I wrote it because it was true. Fifty-eight years later, it still is.

I was born in Brownsville, deep in the interior of Brooklyn, in 1930 to immigrant Jewish parents from Central Europe. The East River that separated us from Manhattan was, to me, a towering border, a dividing line between worlds. We didn’t use the word Manhattan growing up—we called it New York, not because we didn’t know that we, too, lived in New York, but because the separation felt so vast that we needed language to make sense of it.

On one side of the river lay a troubled, crime-ridden slum, split in thirds between Jews, Italians, and blacks. A gang stood on every street corner; violence and drinking were ubiquitous.

On the other, Manhattan: a glittering fortress of class and intellect.

It was there where I would attend Columbia University, serve as the editor in chief of Commentary magazine for 35 years, and meet Jackie Kennedy and Henry Kissinger. It was there I’d be welcomed into a world of royalty, then thrown to the curb by that world, mercilessly.

Manhattan has been my home for more than 70 years. Physically, I made it there early on. But spiritually, I have remained suspended between the two worlds, sustained by both, even as they nearly pulled me to pieces.

At 95 years old, I have never stopped living a double life.

When I was 6, I nearly died of pneumonia. It was 1936, and there was no reliable cure; sulfur was the only medicine available to children, and it often caused more harm than good.

I was bedridden for nearly six months. I remember my mother taking my temperature and bursting into tears when she read the thermometer. In those days if you had a 104-degree temperature at 6 years old, you were unlikely to make it to 7.

But I survived. I escaped death. And two years later, I began to write.

It began with a typewriter, an Italian portable that my parents saved up to buy so they could help prepare my sister for work as a stenographer. My sister, five years older than me, was a gifted student, but like most girls her age, she was not expected, nor invited, to attend college.

That typewriter was the greatest object I’d ever seen. I was forbidden from using it, which naturally meant that I did so every time I could find an opportunity. At first, I copied newspaper stories, rapidly learning to type at 100 words per minute. But I grew bored, disenchanted with simple copying, and soon began to write poems. I don’t know where that idea came into my head, but I loved to read, and I loved to write, and it turned out I was quite talented at it. That wasn’t typical for Brownsville.

Read

Falling in Love on the Back of a Motorcycle

In those days, Brownsville was notorious as one of the murder capitals of the world, consumed by tribalism, violence, and poverty. My “gang” was the Cherokees, a neighborhood group whose red satin jackets bore large white letters spelling “Cherokees, S.A.C.,” which stood for “social-athletic club.” I wore that jacket to school every day.

I was fiercely proud of Brownsville, and of the Cherokees. But I wasn’t quite built for them. Their currency was power and athleticism, and I was a small child, a subpar athlete, and invariably the teacher’s pet every year. I excelled at school, winning endless prizes, beginning with an essay contest in second grade about a field trip to the Hydrox ice cream factory. At my sixth-grade graduation ceremony, almost all the medals that were awarded went to me. Our family doctor, who was sitting next to my mother in the audience, asked her resentfully, “When is he going to stop winning the medals?” My mother was disgustingly proud. I was simply embarrassed.

But unlike others in the neighborhood, the Cherokees didn’t ostracize or put me down. They took pride in my differences, in my achievements, and with them, I felt at ease. From a very young age, I had literary ambitions, but never social ones. I didn’t want to break from the community I’d found—I only wanted to write.

That choice, however, wasn’t left up to me. One of my high school teachers, Mrs. K, took me under her wing, calling me, with her own peculiar affection, a “filthy little slum boy” and deciding she was going to get me into Harvard. She sought to change everything about me: my manners, my clothes. She took me to her house, and to fancy restaurants and museums in Manhattan; she offered to buy me a nice suit, and she loved me. Unlike her, I saw no connection, nor did I want to see one, between a predilection for poetry and an interest in highbrow fashion. She tried desperately to make me understand that I could not enter the literary world I desired without leaving the social one that had raised me.

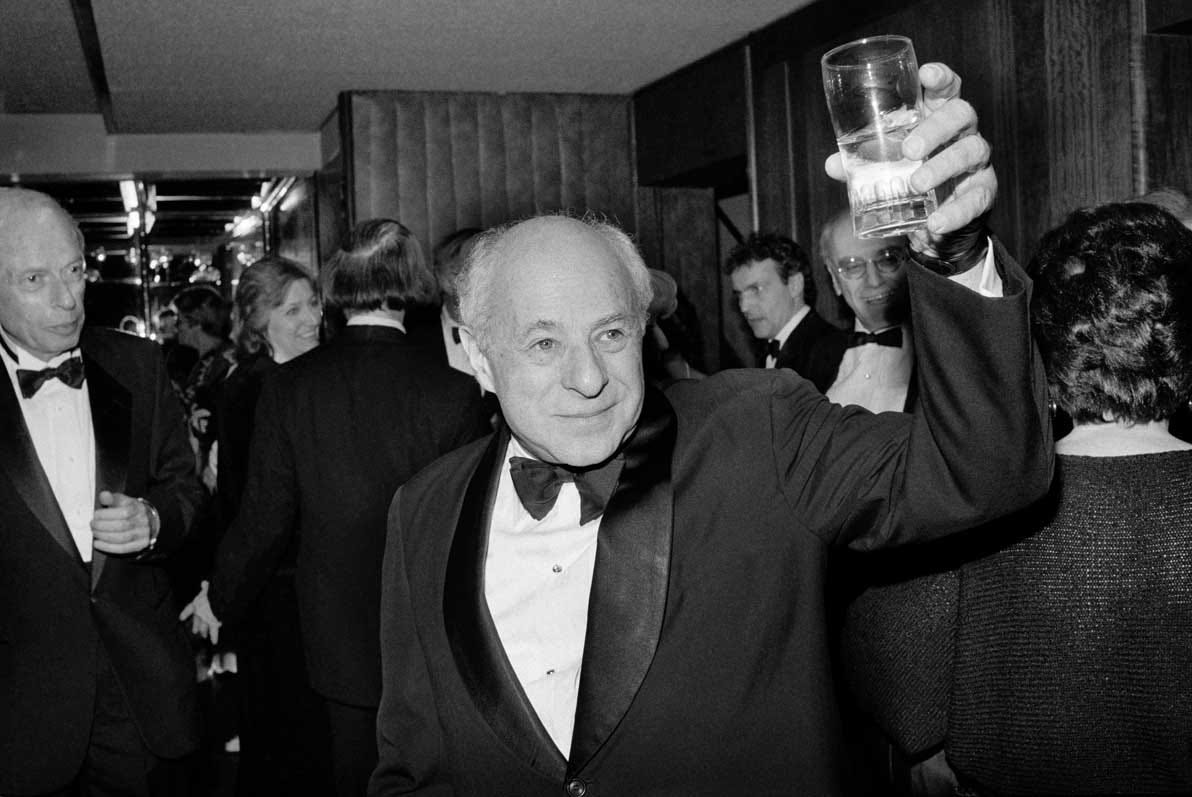

Norman Podhoretz attends a party in his honor in New York on January 29, 1985. (William E. Sauro/The New York Times/Redux)

And so, my two lives, one on the streets, and another in school, coexisted uneasily. They would continue to do so for the rest of my life.

In the end, Mrs. K was forced to settle for Columbia instead of Harvard. I earned a full scholarship, but I couldn’t afford to live on campus, so in those days I traveled from Brooklyn to Manhattan every day—but only physically. Even with all of Mrs. K’s prodding, I hadn’t grasped the rules of Manhattan. I showed up to my first day of college in my satin red Cherokees jacket, only to find everyone else in sports coats and ties. She was right. I hadn’t realized how much clothing could matter, how much it could brand you.

I learned the rules, after that. I thrived at Columbia, mentored by the great literary critic Lionel Trilling, whose guidance carried me to Cambridge University in England. From Brownsville to Cambridge—you can hardly imagine a greater distance. Over time, I shed the red satin jacket, the “bad” manners, the identifying features of my old neighborhood. There were many famous athletes who emerged from Brownsville over the years, and most of them returned regularly to their old local haunts. But my departure from Brooklyn was intellectual as well as physical, and therefore all-encompassing. It was not nearly as reversible.

By age 29, as the 1960s were beginning, my world in Manhattan had swelled. I was editor in chief of Commentary, spending my days among New York’s dazzling intellectual aristocracy: Hannah Arendt, Irving Howe, Norman Mailer. . . and Jackie Kennedy.

Jackie Kennedy moved to Manhattan in 1964, shortly after the assassination of her husband, desperate to piece together a new identity. She began to organize small parties for intellectuals in the city, and she asked me to host one of them. I agreed.

My wife was livid, accusing me of selling out, of chasing after the glamorous lifestyle that all my peers wanted: the Park Avenue apartment, the social prestige, the belonging. In some ways, she was right. Those parties were intimate—10 to 15 guests, every one of them famous, every one of them sought after. It was irresistible.

But at the same time, I was embarrassed by the glitz and pretension. Even then, I couldn’t shed Brownsville, not even if I had wanted to. I was just across the river but worlds away from home, from the Cherokees, from my life on the streets. I had never wanted the Park Avenue lifestyle, but Manhattan society has a way of pulling you in.

Someone once asked me what I was ambitious for. Fame and glory, I said. Not money, and certainly not society. What I wanted was to write, and to be known for having written. What I discovered, over the years, was that you couldn’t have one without the other.

Until I did.

Read

Chris Rufo: Why My Sons and I Take the Train

In 1967 I published a book, Making It, which began with that famous line about my journey. What it was really about was ambition: the “dirty little secret of the well-educated American soul.” New York’s intellectual class, I wrote, was nakedly, desperately ambitious for status and power. We pretended to modesty and humility, because we were ashamed of our vanity, and because we thought, incorrectly, that ambition was one of the great cultural sins of our time.

I was writing the truth, or at least what I perceived to be true.

But the literary world saw it as heresy; we intellectuals were meant to aspire to higher things than status. Friends turned on me without a thought. “A real man doesn’t brag about his marks,” Jackie Kennedy said to someone I knew. That marked the abrupt end of our friendship. My publisher refused to promote the book. The New York Review of Books savaged me, as did nearly every other major publication in the city.

This world, this Manhattan social world that had unsettled me, courted me, drawn me in—it now cast me out, all at once. Lionel Trilling, my mentor, had warned against publishing, predicting it would take 10 years to recover. He was wrong. It took 20. My life unraveled. I couldn’t write for a long time. I stopped going to parties, the very parties that had once measured the progress of my career. I contemplated ending my life.

That book brought my balancing act between Brooklyn and Manhattan crashing down.

In a peculiar way, my journey began when I escaped death at 6 years old, which I learned later was a very close call. It makes me laugh to think about how many people, how many of my former friends, might have reacted if they knew about my early brush with death. Damn, they might have said. If only.

But I was, after all, rather good at escaping dire situations. The trauma of falling from the precipice of New York’s intellectual aristocracy in 1967—a kind of social death—has stayed with me ever since. But over time, as I sat with and bore it, refusing to apologize for its truth or hide it from public view, the immediacy of the pain softened.

My journey from Brooklyn to Manhattan is one of the longest in the world, because it never truly ended. I’ve carried both cities within me all this time.

In its place came opportunity. Having long been a man on the left, I gradually moved toward political conservatism. I found new intellectual circles and published more than a dozen books. Thirty-seven years after the release of Making It, I received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush. I clawed my way back into New York’s royalty—this time, the conservative side of it—and then, still, couldn’t help but be embarrassed by it all. But it allowed me to keep writing, and to keep writing honestly. That’s what mattered. And in 2017, New York Review Books, the publishing house of the magazine that had once excoriated my book, republished Making It as part of their Classics series. Manhattan, it turned out, had come around on me.

I’ve lived a rich life, in every sense. I am 95 years old. I have 13 grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren, and every morning when I wake up, I marvel that I am still here. And I was right, in the end: My journey from Brooklyn to Manhattan is one of the longest in the world, because it never truly ended. I’ve carried both cities within me all this time.

That double life, Brooklyn and Manhattan, grit and glamour, loyalty and betrayal, nearly tore me apart. Yet it also saved me. It kept me honest, in a world where honesty was a rare currency, ambition was a sin, and the combination of the two gave me everything I have.

—As told to Jillian Lederman.

Norman Podhoretz’s Prayer

He knew his remarkable life was only possible in America, and he thanked God for its blessings.

By Matthew Continetti – Dec. 19, 2025 6:46 am ET – Wall Street Journal

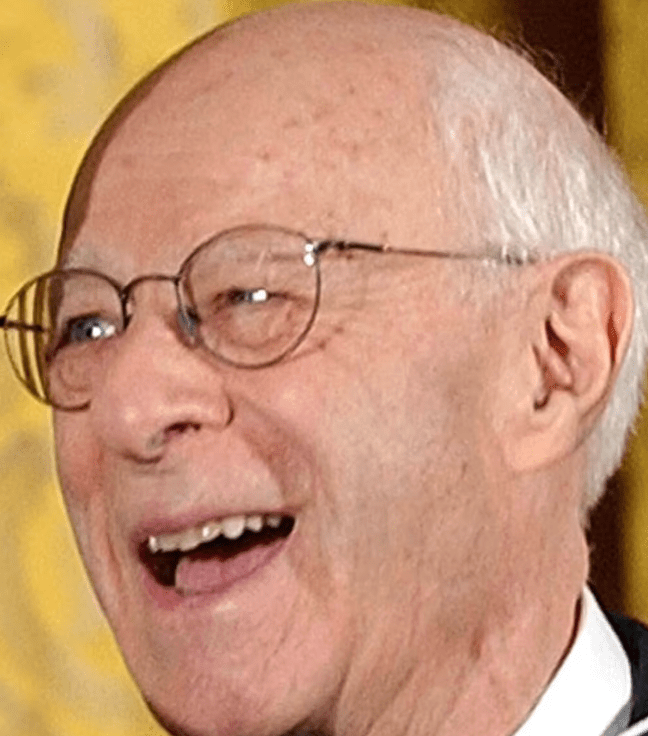

Norman Podhoretz receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom at the White House on June 23, 2004. Photo: Susan Walsh/Associated Press

The author and editor Norman Podhoretz will be remembered for a life of achievement and distinction. I am grateful for his courage.

Podhoretz, who died Tuesday at 95, never flinched from stating his views honestly and directly. Whether he was debating literature or Zionism, extolling Bach or analyzing an election, Podhoretz was clear, unvarnished and unapologetic. He never suffered from a failure of nerve. He said what he thought—even when his positions were contrary to those of his allies and his views put at risk friendships on both left and right.

This boldness was sometimes mistaken for sheer ambition. No question, Podhoretz felt an inner drive to succeed. He dreamed of surmounting the social and economic circumstances of his birth in working-class Brownsville, Brooklyn, in 1930. He didn’t shirk from success. Nor did he believe anyone else should either.

“I was born with certain gifts,” he wrote in 2000. “I worked hard to cultivate and then to use them as fully as I had it within me to do, and in that way I earned the rewards they brought without special favors or allowances, and often even in defiance of those with the power to withhold or deprive me of those rewards.”

He was precocious indeed. Podhoretz enrolled at both Columbia and the Jewish Theological Seminary when he was 16 years old. Upon Podhoretz’s graduation, his mentor, Lionel Trilling, helped send him to Clare College at Cambridge for further study and a master’s degree. After a stint in the Army in the early 1950s, Podhoretz began writing the dazzling literary criticism that made his reputation among the New York intellectuals—a tough crowd to please.

This rapid ascent culminated in 1960 when Podhoretz, 29, became editor of Commentary. By the time he retired from the magazine in 1995, he had shaped not one but two intellectual revolutions: first, the radical politics behind the New Left of the 1960s; then, beginning in the early 1970s, the neoconservative critique of the anti-American counterculture and its liberal apologists. Through it all—as well as in his 12 books and countless essays, articles, columns and interviews—Podhoretz delivered his judgments on the national condition without fear of rebuke or of giving offense.

In spring 1971, for example, Podhoretz spoke to an audience at the American Jewish Committee, which sponsored Commentary magazine from 1945 until 2007. Podhoretz told his benefactors that “a certain anxiety” had been troubling him. Israel’s success in the Six Day War of 1967 had ushered in a new era of antisemitism, fueled by the Soviet Union and the Arab League, under the guise of anti-Zionism.

Disturbing signs also appeared closer to home. Soon after the war, Podhoretz went on, the New York City teachers’ strike of 1968 exposed a frightening divide between blacks and Jews. What disturbed Podhoretz was that liberals had ignored, played down or justified malice and even violence on the part of groups endowed with victim status. A sense of collective guilt mixed with class condescension paralyzed liberalism. “Worst of all, perhaps, were my fellow intellectuals,” he wrote in retrospect.

The audience was unmoved. The applause was minimal, the questions hostile. One AJC employee left the room in a huff. Another accused Podhoretz of trying to silence all criticism of Israel. A third blamed racial tensions solely on Albert Shanker, the Jewish president of the United Federation of Teachers.

A fourth AJC staffer couldn’t possibly understand why Podhoretz might feel that over the past decade the radical left had displaced the radical right as the primary threat to American Jews and American civilization. “Before I could answer this outburst,” Podhoretz wrote many years later, “I had to wait for the thunderous applause it elicited to die down.”

Some things don’t change.

Yet Podhoretz was undeterred. He had arrived at several conclusions he couldn’t shake. First, the forces threatening Jewish security also endangered America. Second, these forces ultimately were animated by the ideas and attitudes of academics and intellectuals. And third, his mission, and Commentary’s, would be to debunk such ideas while aggressively affirming the political and economic institutions that continued to make the U.S. an exceptional country. If his funders at the AJC disapproved, well, so be it.

This task carried a price. “I have often said that if I wish to name drop, I have only to list my ex-friends,” Podhoretz wrote. He became politically homeless. He and Midge Decter, his beloved wife and intellectual companion who died in 2023, moved from one camp to the next: from radicalism to social democracy to liberal centrism to neoconservatism and, finally, to Ronald Reagan’s GOP.

As he defended American foreign policy, capitalism, Judeo-Christian values and the state of Israel, Podhoretz was demeaned and disparaged. He was accused of dual loyalties and called a bigot, a warmonger and a bully. He could have retreated. He could have toned down his rhetoric.

He did not. His devotion to the Jewish people, to the American idea and to the blessings of liberty was implacable. And though he discovered (and helped to grow) an intellectual community on the right, and indirectly influenced the direction of the Republican Party, Podhoretz wasn’t afraid to challenge his newfound comrades. If he saw conservative resolve weaken, if conservatives allowed antisemitism to emerge from the fever swamps or if conservatives began to drift away from the sources of American greatness, Podhoretz would remind them of the stakes. Forcefully.

Thus, in the early 1980s, Podhoretz lamented the direction of Reagan’s foreign policy in much-discussed essays for the New York Times Magazine and Foreign Affairs. While liberals cast Reagan as a trigger-happy dunce, Podhoretz criticized the president for excessive caution. People noticed. Reagan called Podhoretz to defend his administration—the only time, Podhoretz would say, that the two men discussed foreign policy.

When antisemitism appeared on the right at the end of the 1980s, Podhoretz wrote stinging letters to National Review editor and conservative intellectual William F. Buckley Jr., imploring him to act. The correspondence partly inspired Buckley’s confessional essay “In Search of Anti-Semitism,” published in book form in 1992. Buckley admitted to youthful antisemitism and explained his decision to dissociate from friends and contributors whose obsession with Israel had mutated into a pernicious fixation on Jews. “Take it for all in all,” Podhoretz wrote, “ ‘In Search of Anti-Semitism’ represented another ‘generic step’ in Buckley’s campaign to keep anti-Semitism out of the conservative movement.”

In 1997, the editors of First Things, a conservative journal with a special interest in religion, published a symposium on recent Supreme Court decisions. Some of the contributors called into question the legitimacy of the American regime and asked if civil disobedience had become necessary to protest the judicial imposition of abortion and gay rights.

Podhoretz sprang into action. He rebuked the editor of First Things, Father Richard John Neuhaus, for flirting with rhetoric that was a staple of the far left. “I did not become a conservative in order to become a radical,” he wrote to Neuhaus, “let alone to support the preaching of revolution against this country.” Neuhaus subsequently backed away from some of the symposium’s more controversial claims.

During the 2000s, when parts of the right distanced themselves from George W. Bush’s global war on terrorism, Podhoretz continued to argue that the U.S. was fighting “World War IV” and that the war could not be won if Iran obtained a nuclear weapon.

And in 2016, when many of Mr. Bush’s intellectual supporters forswore Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy, and in some cases broke ranks with conservatism altogether, Podhoretz supported Mr. Trump as the lesser evil. “If Iran gets a nuclear weapon, I think that we would be in great danger of seeing an outbreak of a nuclear exchange between Iran and Israel,” Podhoretz told the Times of Israel. “So that alone would be enough to turn me against the Obama administration and virtually everyone who took part in it, and certainly Hillary Clinton. It overshadows everything from my point of view.”

Nine years later, Mr. Trump authorized Operation Midnight Hammer, reducing Iran’s nuclear program to ash.

What was the source of Podhoretz’s courage? His patriotism. He was fearless because he knew that his life was possible in America alone. “What made the American Revolution so revolutionary,” he wrote, “was that it set up a system in which, for the first time in human history, individuals were to be treated as individuals rather than on the basis of who their fathers were.”

It is no accident, Podhoretz understood, that America promotes human flourishing. It is the result of ideas and institutions whose legitimacy is forever being challenged and requires a stalwart defense.

Such a defense begins with an appreciation of the American inheritance. Podhoretz ends his most heartfelt book, “My Love Affair with America” (2000), with a personal version of the Haggadah’s dayenu prayer that he devoted to America. A highlight of the Passover Seder, “dayenu” itemizes all that God has done for the Hebrews. Every line ends with the word “dayenu,” meaning “that would be enough.” The point is God’s blessings are beyond count.

Podhoretz’s version of the prayer includes his thanks at receiving the gifts of the English language, of education here and abroad, of a chance to make a career out of intellectual work, of opportunities to meet the great and good and not so good, of editing Commentary and of providing resources for beautiful homes where he could write happily into his 10th decade.

“In the end,” he wrote, “I suppose it all comes down to gratitude.” Gratitude for America and for those who, like Norman Podhoretz, courageously champion the cause of freedom. Dayenu.

Mr. Continetti is a Free Expression columnist at WSJ Opinion.

Leave a comment