Meet the woman responsible for making you slog thru “War and Peace” in High School

By History Nerds on Facebook

Sofia Behrs was eighteen years old when she married Leo Tolstoy in 1862. He was thirty-four, already a celebrated author. She was the daughter of a court physician, educated, intelligent, full of romantic ideals about what marriage to a great writer would mean.

On their wedding night, Tolstoy handed her his diaries. “Read these,” he said. “I want complete honesty between us.” The diaries detailed his sexual affairs with peasant women on his estate, his gambling debts, his past indiscretions. Everything he’d done before meeting her.

Sofia read them and was devastated. This was her introduction to married life: complete transparency about her husband’s past, including relationships with women who still lived and worked on the estate where she was now mistress.

But she loved him. And she believed in his genius. So she stayed. What followed was fifty-eight years of marriage that produced thirteen children (five died in childhood), some of the greatest novels in world literature, and a partnership so complex it’s impossible to categorize as simply good or bad.

Sofia became everything Tolstoy needed to create his masterpieces.

When he wrote War and Peace, he produced chaotic drafts—pages covered in nearly illegible handwriting, crossed-out sections, marginal notes, inserts written on scraps of paper. Sofia deciphered his handwriting (which few others could read), organized the chaos, and copied the entire massive manuscript by hand. Multiple times. Some sources say seven full copies, though the exact number is disputed—what’s certain is that she spent years copying and recopying as Tolstoy revised endlessly.

She didn’t just copy mechanically. She edited. She made suggestions. She caught inconsistencies. She functioned as his first reader and collaborator. And she did this while pregnant, while nursing infants, while managing a household with eight surviving children.

Then came Anna Karenina. Again, Sofia copied the manuscript by hand through multiple drafts. Again, she managed the household while Tolstoy wrote.

But she was more than a copyist. She negotiated with publishers. She managed the family finances. She protected Tolstoy’s copyright and ensured his work was properly compensated. She made him wealthy. She made him possible.

Tolstoy’s genius was real—but it existed within a structure Sofia built and maintained. Then, around 1880, Tolstoy had a spiritual crisis. He became obsessed with Christianity, poverty, simplicity. He renounced his noble title. He dressed in peasant clothes. He made his own boots. And he decided the family should give away their wealth. Including the copyright to all his works.

Sofia was horrified. They had eight children to support and educate. The estate required income to maintain. The family’s financial security depended on Tolstoy’s literary earnings—earnings that existed because of her labor.

Tolstoy insisted material wealth was sinful. Sofia insisted their children needed to eat.

The conflict consumed their later years. Tolstoy’s followers—disciples who worshipped his philosophy of poverty and simplicity—sided with him. They saw Sofia as materialistic, as standing between Tolstoy and his spiritual ideals.

Sofia saw herself as protecting her family from her husband’s increasingly impractical philosophy. The tension destroyed what remained of their marriage.

Tolstoy wrote in his diary that marriage was a mistake, that family life prevented spiritual enlightenment. Sofia read these entries (they’d long since abandoned any pretense of privacy) and wrote her own furious responses in her diary.

She attempted suicide multiple times—once by lying on train tracks, once by jumping in a frozen pond. Each time she survived, and the marriage continued.

By 1910, Tolstoy was eighty-two and Sofia was sixty-six. Their home had become a battleground between Sofia fighting to maintain the family finances and Tolstoy’s followers encouraging him to abandon his family entirely.

On October 28, 1910, at 5 AM, Tolstoy fled. He left a letter for Sofia: he was leaving to live his final days in solitude, away from family conflict, pursuing the simple life his philosophy demanded.

Sofia was devastated. Destroyed. The man she’d spent fifty-eight years supporting, whose genius she’d enabled with her labor—he’d abandoned her. She pursued him. She tracked his movements through railway stations. Within days, Tolstoy fell ill with pneumonia at Astapovo railway station. He was dying.

Sofia arrived at the station. She begged to see her husband.

Tolstoy’s followers, led by their daughter Alexandra and his secretary Vladimir Chertkov, refused. They physically barred Sofia from entering the stationmaster’s house where Tolstoy lay dying. They told her she was too emotional, that seeing her would upset him, that she’d caused him enough suffering. For days, Sofia waited outside in the November cold while her husband died inside. Only when he was unconscious, when he could no longer know she was there, were they finally allowed to let her into the room.

Leo Tolstoy died on November 7, 1910. Sofia sat beside him, having been kept from him in his final conscious moments by the people who’d spent years telling him to abandon her.

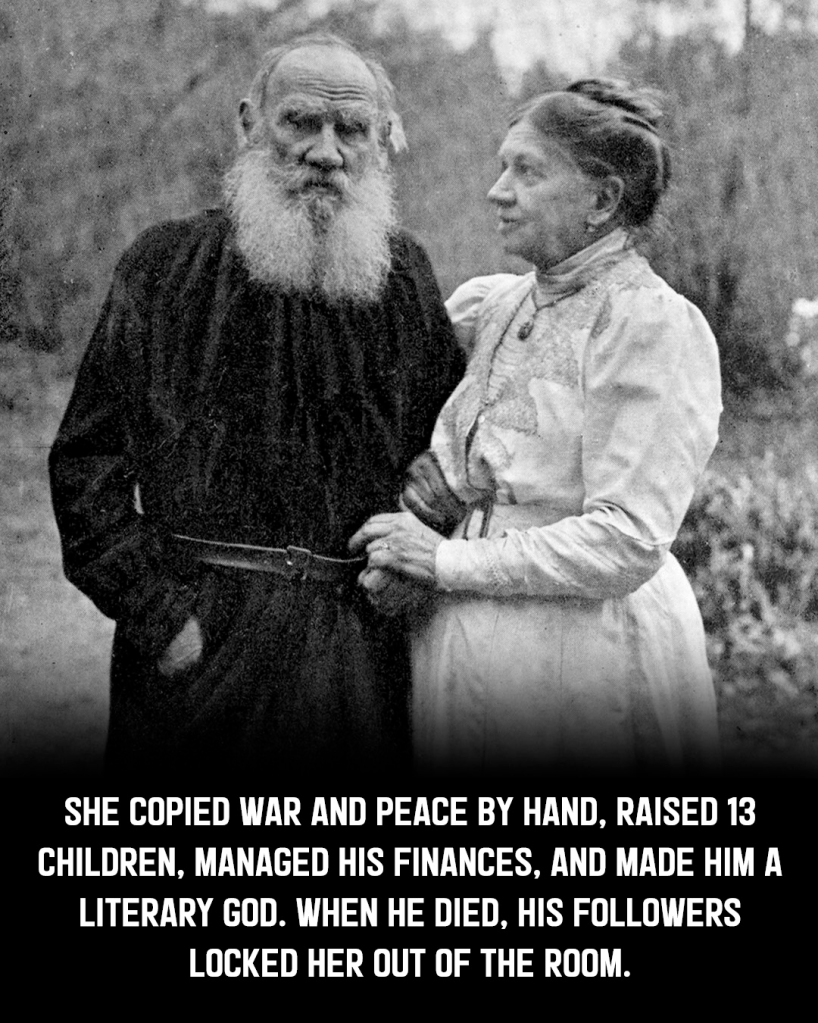

The image became symbolic: Sofia Tolstaya, locked out of the room where her husband died, just as history has so often locked her out of his story.

After Tolstoy’s death, Sofia dedicated herself to preserving his legacy. She organized his papers. She prepared editions of his work. She turned their estate into a museum. She lived nine more years, dying in 1919 at age seventy-five, having outlived Tolstoy and outlived the Russian Revolution that destroyed the world they’d known.

Today, everyone knows Leo Tolstoy. His novels are taught in schools worldwide. He’s considered one of the greatest writers in history. Sofia Tolstaya is a footnote. The wife. The woman who copied manuscripts.

But the truth is more complex and more profound.

War and Peace and Anna Karenina exist because Sofia made them possible. She deciphered chaos and turned it into legible manuscripts. She managed the household that gave Tolstoy the space to create. She negotiated the publishing deals that made his work reach millions.

She was his partner in the truest sense—not just emotionally, but practically, intellectually, economically.

And when Tolstoy’s philosophy demanded he give away everything, Sofia fought to protect the family and the legacy she’d helped build.

Was their marriage happy? No. It was often miserable, especially in later years. But was Sofia essential to Tolstoy’s work? Absolutely. Without her labor, War and Peace might have remained an illegible manuscript in a drawer. Without her financial management, the Tolstoy family would have been destitute. Without her defense of his copyright, his works might not have reached the audiences they did.

Sofia Tolstaya wasn’t just behind the great man. She was the foundation he stood on. History remembers the author. But the masterpieces were written by two people—one with a pen, one with patience, precision, and the invisible labor that makes genius possible.

When Leo Tolstoy died, locked in that railway station room, Sofia stood outside in the cold. She’d stood outside his glory for fifty-eight years—working, copying, managing, enabling.

It’s time we let her in. Not as a footnote to his genius, but as a partner in creating it. Sofia Tolstaya: the woman who turned scribbles into War and Peace. The woman who made Tolstoy possible.

===================================================

A very good and even handed approach to understanding “War and Peace” can be found in Sparknotes.

From Google’s Ai overview:

Ah, the shared struggle of high schoolers tackling Tolstoy’s epic, War and Peace! It’s a rite of passage, often marked by massive page counts, endless Russian names (with multiple versions!), and philosophical detours, but also rewarded with deep insights into life, history, and human nature, with many finding it an incredible, albeit challenging, journey worth taking with a good character list and patience.

Common High School Experiences & Tips:

- The Name Game: Keeping track of the many characters (Pierre, Andrei, Natasha, etc.) and their complex Russian names (and nicknames!) is a classic hurdle.

- Pacing is Key: It’s a marathon, not a sprint; reading slowly, taking breaks, and sometimes using an audiobook alongside the text helps.

- Embrace the Slog (and the Philosophy): Don’t expect a fast-paced thriller; it demands focus but rewards with profound reflections on life, war, and consciousness.

- Tools Help: A character list (often printed or online) and a basic understanding of Napoleonic history make it much smoother.

Why It’s Worth It (Even if it’s a Slog):

- Masterpiece Status: It’s considered one of the greatest novels ever, offering deep insights.

- Realistic & Deep: Tolstoy doesn’t sugarcoat life, presenting blunt, realistic portrayals of people and events.

- A Rewarding Challenge: It’s a fulfilling experience that builds a stronger understanding, making it a rewarding, if difficult, read.

So, to all who survived it, you’ve conquered a literary giant, and many who revisit it later find even more joy in its depth.

Leave a comment