For the philosopher, unhappiness became not a condition but a vocation.

By Adam Kirsch – May 4, 2020 – The New Yorker

My cmnt: Timothy Keller, in his book The Reason for God, used Soren Kierkegaard’s definition of sin: Sin is: in despair not wanting to be oneself before God … Faith is: the self in being itself and wanting to be itself is grounded transparently in God.” Sin is the despairing refusal to find your deepest identity in your relationship and service to God. Sin is seeking to become oneself, to get an identity, apart from him. (pg 162)

My cmnt: This strikes me as liberal gobbledygook. Like the language of democrat politicians. Camela Harris, ‘”What can be, unburdened by what has been.” -or- “It’s time for us to do what we have been doing and that time is every day.” I would define sin as: Seeking for our needs to be met in unrighteous ways. “Therefore do not be anxious, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’ For the Gentiles seek after all these things, and your heavenly Father knows that you need them all. But seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be added to you.” Matt 6:31-33

My cmnt: I find Kierkegaard a sociopath and possibly or very likely demon possessed. His influence on the Gospel has been devastating to the Protestant Christian world and seems to be a major cause of the rise of Liberalism in biblical interpretation. His interpretation of Abraham’s commission by God to offer his son Isaac (his ONLY son tho’ he had another son, his firstborn whom he loved, Ishmael) is nearly completely garbled up by Kierkegaard. This novel and bizarre interpretation is recorded below so I won’t repeat it here.

My cmnt: The author of Hebrews gives us the true and biblical understanding of this famous story. “By faith Abraham, when he was tested, offered up Isaac, and he who had received the promises was in the act of offering up his only son, of whom it was said, “Through Isaac shall your offspring be named.” He considered that God was able even to raise him from the dead, from which, figuratively speaking, he did receive him back.” Heb 11:17-19. Abraham did not pursue “blind faith” nor a “leap of faith” but rather the faith that understood that God, the author of life, gives life to the dead.

My cmnt: “Therefore, the promise comes by faith, so that it may be by grace and may be guaranteed to all Abraham’s offspring—not only to those who are of the law but also to those who have the faith of Abraham. He is the father of us all. As it is written: “I have made you a father of many nations.” He is our father in the sight of God, in whom he believed—the God who gives life to the dead and calls into being things that were not. Against all hope, Abraham in hope believed and so became the father of many nations, just as it had been said to him, “So shall your offspring be.” Without weakening in his faith, he faced the fact that his body was as good as dead—since he was about a hundred years old—and that Sarah’s womb was also dead. Yet he did not waver through unbelief regarding the promise of God, but was strengthened in his faith and gave glory to God, being fully persuaded that God had power to do what he had promised. This is why “it was credited to him as righteousness.” The words “it was credited to him” were written not for him alone, but also for us, to whom God will credit righteousness—for us who believe in him who raised Jesus our Lord from the dead. He was delivered over to death for our sins and was raised to life for our justification.” Rom 4:16-25

My cmnt: I’ve written elsewhere on this website a sermon about the meaning of the Gospel. The most basic question the Gospel asks is this: Is God good? If God is good then it is only reasonable that we place our trust in Him, both now and forever. But such reasoning, as with Kierkegaard, is beyond dead men. The natural man hates God and runs from Him. That man is dead in his trespasses and sins. God to the natural man produces only fear and loathing. It is only thru God the Holy Spirit raising a dead man to life that a dead man can see and understand his hopelessness outside of Christ and can cry out to God and receive eternal life.

===================================================

Imagine an educated, affluent European in his late twenties, seemingly one of fortune’s favored, who suffers from crippling feelings of despair and guilt. For no apparent reason, he breaks up with the woman everyone thought he was going to marry—not because he loves someone else but out of a sudden conviction that he is incapable of marriage and can only make her miserable. He abandons the career for which he has been studying for ten years and holes up in his apartment, where a kind of graphomania compels him to stay up all night writing at a frantic pace. His activity is so relentless that, in a few short years, he has accumulated many volumes’ worth of manuscripts.

If this happened today—say, in Denmark, the standard example of a rational modern society—the man would sooner or later end up in a psychiatrist’s office, where he would probably be given a diagnosis of depression or bipolar disorder. He would start seeing a therapist and might be prescribed medication. The goal would be to get him back to normal, as the world defines “normal”: able to take pleasure in life, to form relationships, to meet his obligations as a family member, friend, and citizen. The man would seek professional help, because, in the twenty-first century, he would recognize his propensities as symptoms—evidence of a psychological problem.

But when Søren Kierkegaard underwent these experiences in the Denmark of the eighteen-forties they had a different meaning. “At times, there is such a noise in my head that it is as though my cranium were being lifted up, it is exactly like when the hobgoblins lift a mountain up a little and then hold a ball and make merry inside,” he wrote in his journal in February, 1838, when he was twenty-four. But Kierkegaard had learned from Romantic literature that wild emotion was a sign of genius, especially when it was painful. “Real depression, like the ‘vapors,’ is found only in the highest circles, in the former case understood in a spiritual sense,” he wrote two months later. He considered his “melancholy” not a disease but a “close confidant . . . the most faithful mistress I have known.”

Side by side with this fashionable style of feeling, Kierkegaard inherited from his ancestors a rigorously introspective Protestantism. His father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, had grown up poor in the countryside, moved to Copenhagen to become a merchant, and ended up as one of the city’s richest men. Michael Pedersen raised his seven children, of whom Søren was the youngest, under strict religious discipline, instilling a sense of fear and guilt that never left them. “Oh, how frightful it is when for a moment I think of the dark background of my life, right from the earliest days!” Kierkegaard recalled. “The anxiety with which my father filled my soul, his own frightful melancholy.”

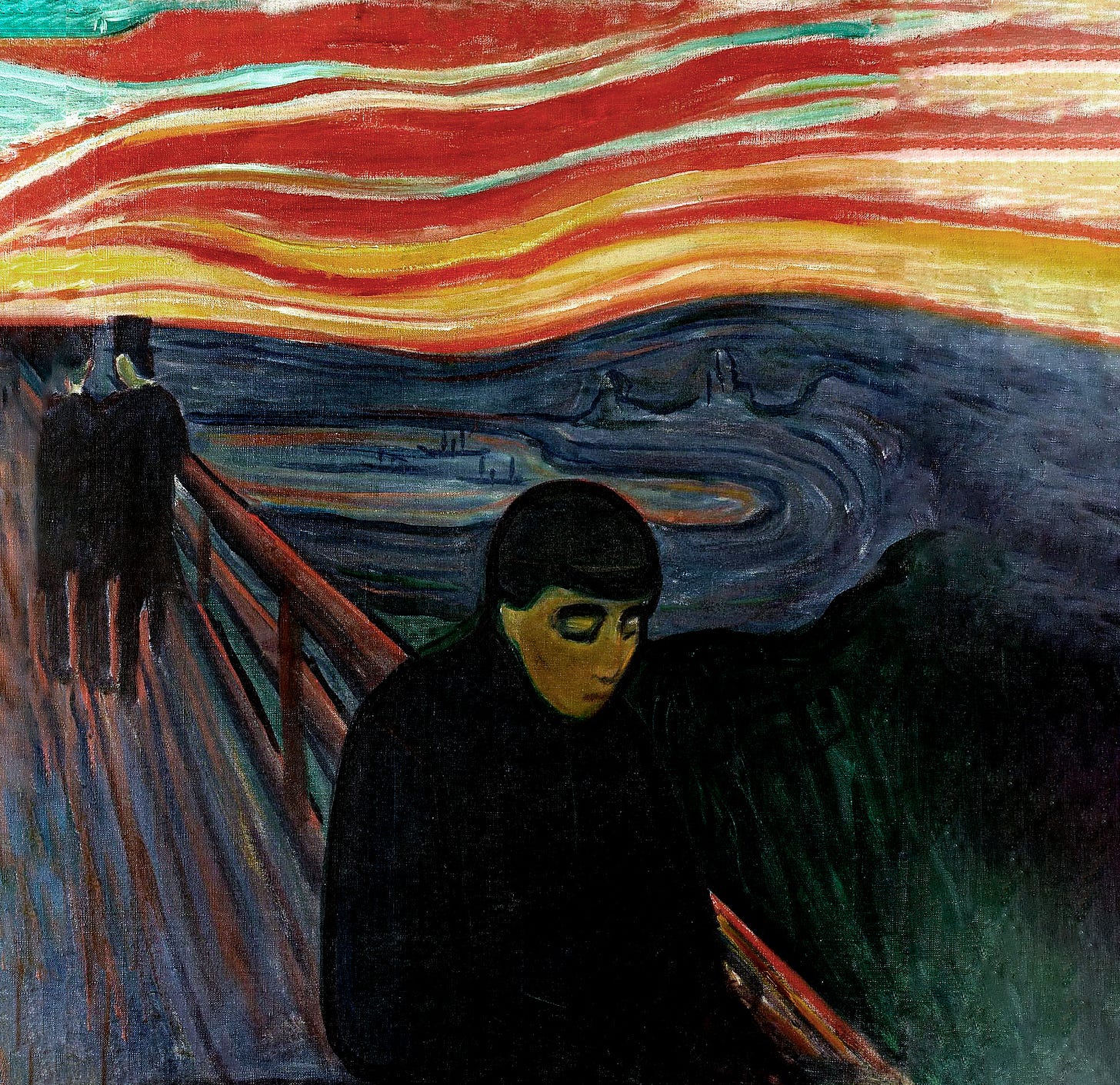

For Kierkegaard, unhappiness became not a condition but a vocation. In a new biography, “Philosopher of the Heart” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), the British scholar Clare Carlisle shows that this calling consumed his life. After leaving school, at the age of seventeen, in 1830, he enrolled as a theology student at the University of Copenhagen, in order to prepare for a career in the church. But it took him ten years to complete his degree, and he never became a pastor or had any other kind of job. He never got married or had children. Other than a few visits to Berlin, then the capital of philosophy, and one trip to Sweden, Kierkegaard never left Denmark. He took no interest in politics. In 1848, the liberal revolutions sweeping Europe reached Denmark, as protests forced the king to promise a new constitution and parliament; but Kierkegaard was indifferent. “So the king flees—and so there is a republic,” he wrote in his journal that year. “Piffle.”

What he did instead was write. Until his death, in 1855, at the age of forty-two, Kierkegaard lived off his inheritance and produced a stream of unclassifiable books—hybrids of philosophy, autobiography, fiction, and sermon. Advancing deeper and deeper into the experience of suffering, he emerged with a profoundly new way of thinking about human existence. The dark exigency of Kierkegaard’s books, which he sometimes published two or even four at a time, is plain from their titles: “Fear and Trembling,” “The Concept of Anxiety,” “The Sickness Unto Death.”

In that last book, which appeared in 1849, Kierkegaard offers an uncompromising diagnosis of the human condition. “There is not a single human being who does not despair at least a little, in whose innermost being there does not dwell an uneasiness, an unquiet, a discordance, an anxiety in the face of an unknown something,” he writes. If you don’t think you are in despair, you are lying to yourself, which is an even worse form of despair. Only by acknowledging our condition, he says, can we begin to understand that the true name of despair is sin, defiance of God. We are freed from it only when we accept that “a human self is under an obligation to obey God—in its every secret desire and thought.”

This understanding of sin and redemption wasn’t Kierkegaard’s invention. Something like it was preached in Denmark’s Lutheran churches every Sunday. What made his work explosive was his insistence that those very churches had become the chief obstacles to genuine Christian belief. Nineteenth-century Europeans took for granted that they were Christians simply because they were living in “Christendom,” in countries where there were “just as many Christians as there are people,” he wrote. But a Christian, for Kierkegaard, isn’t something you are born; it is something you have to become through terrific inner effort. His “authorship,” as he called it, was meant as an alarm bell to wake the modern world from its spiritual slumber.

Kierkegaard published his books at his own expense, and they initially had a tiny readership: the most popular, “Either/Or,” didn’t sell out its first edition of five hundred and twenty-five copies for three years. Nevertheless, he became a local celebrity, thanks mainly to his eccentricities and his penchant for public feuds. The editor of one Copenhagen paper, the Corsair, observed that, in “Kierkegaard’s entire personal appearance and manner, there was something that verged on the comic.” When the Corsair portrayed him in a series of mocking caricatures, in 1846, he became even more notorious. “Every kitchen boy feels justified in almost insulting me . . . young students titter and grin and are happy to see a prominent person trampled on,” he complained.

When he died—probably of tuberculosis, though the diagnosis remains unclear—Kierkegaard had few if any readers outside Denmark. That didn’t begin to change until he found an influential champion in the Danish literary critic Georg Brandes, who, in 1877, wrote the first book about Kierkegaard and brought him to the attention of a wider European audience. (Later, Brandes did the same for Nietzsche.) The first English translations of Kierkegaard appeared in the nineteen-thirties, and it wasn’t until the sixties, more than a century after his death, that the translators Howard and Edna Hong began to produce a complete English edition of his works.

By that time, the Copenhagen eccentric had become one of the most important influences on twentieth-century theology and philosophy. Although the term “existentialism” wasn’t coined until the nineteen-forties, in retrospect Kierkegaard appears as the first existentialist, thanks to his insistence that life’s most important questions—How should I act? What must I believe?—can’t be resolved by abstract reasoning. They present themselves as urgent problems for each individual, demanding commitment and action. “To be entirely present to oneself is the highest thing and the highest task for the personal life,” he wrote.

The intimate connection between Kierkegaard’s thought and his personal life has made him a compelling subject for biographers. Reading the “Critique of Pure Reason” won’t tell you the first thing about Immanuel Kant, nor do you need to know anything about Kant’s life to understand it. But Kierkegaard’s work emerged, in complex yet unmistakable ways, from his own experiences. Other great thinkers specialize in technical fields such as logic or metaphysics, but Kierkegaard, as Carlisle’s title has it, was a philosopher of the heart, “an expert on love and suffering, humor and anxiety, despair and courage.”

Yet Kierkegaard also resists biography. The genre is inherently opposed to the way he thought about human existence. One of the best-known Kierkegaardian sayings, paraphrased from an entry in his journal, is that life can only be understood backward, but it has to be lived forward. In other words, at every moment, we are making a decision about how to live, one that can’t be made for us by history, society, or even religion—any of the causes that might emerge when we try to analyze the course of our lives in retrospect. My future is no one’s responsibility but my own. This is what Kierkegaard calls “the dizziness of freedom,” which he compares to the vertigo we feel when looking into a “yawning abyss.”

Biography, however, is necessarily written backward. It deals with life as a known quantity, obscuring the reality of contingency and choice. Carlisle, who has published three previous books about Kierkegaard, has tried to avoid this problem by writing what she calls “a Kierkegaardian biography of Kierkegaard,” one that “does not consider Kierkegaard’s life from a remote, knowing perspective, but joins him on his journey and confronts its uncertainties with him.”

In practice, this means that Carlisle tells the story out of chronological order and adds passages of novel-like scene-setting. “Never before has he moved so quickly! And yet he is sitting quite still, not uncomfortably—resting, even—in a ‘marvelous armchair,’ ” the first of the book’s three sections begins. We are with Kierkegaard in 1843 as he takes a train, that new invention, from Berlin to Copenhagen. Carlisle then fills in his story up to 1843, before jumping ahead, in the next section, to 1848 and again filling in the missing years—a cumbersome and sometimes confusing method.

The vignettes feel like packaging that the reader must unwrap to get to what is really excellent in the book: Carlisle’s analysis of Kierkegaard’s intellectual milieu. Copenhagen in the eighteen-forties was a small city of about a hundred and twenty thousand people, but the academic and clerical circles in which Kierkegaard moved were much smaller. His world, Carlisle writes, was “parochial, full of familiar faces”: many of Denmark’s leading clergymen, professors, and writers were his former schoolmates or family friends. And Carlisle shows that Kierkegaard’s books partly emerged out of arguments with these figures—for instance, Bishop Mynster, the head of Denmark’s state church, who became a symbol of everything Kierkegaard detested about official Christianity.

Kierkegaard didn’t seem sure whether he wanted to stand out in this sedate, provincial community or to hide from it. He published under several Latin pseudonyms, which suggests a desire for concealment, but the names were so flamboyantly odd—Johannes de Silentio, Constantin Constantius, Vigilius Haufniensis (that is, “the watchman of Copenhagen”)—that he may well have wanted to draw attention to his authorship.

His identity couldn’t have been concealed for long anyway, since he wrote repeatedly about the one real drama in his life. In October, 1841, when he was twenty-eight, Kierkegaard broke off his year-long engagement to Regine Olsen, a nineteen-year-old from a highly respectable family. His sudden change of heart left her confused and miserable. “So after all, you have played a terrible game with me,” Regine told him when they parted. The public rejection threatened to ruin her future marriage prospects. Carlisle quotes Kierkegaard’s nephew’s recollection of the affair: “It was an insulting break, which not only called forth curiosity and gossip but also absolutely required that every decent person take the side of the injured party. . . . Harsh judgments were unanimously voiced against him.”

Imagine the reaction of local society, then, when, just over a year later, Kierkegaard published “Either/Or,” a long book whose most attention-grabbing section, “The Seducer’s Diary,” is a first-person account of a man’s callous pursuit of a young girl, whom he manipulates into submission and then discards. “Now it is over and I want never to see her again. Once a girl has given away everything, she is weak, she has lost everything,” the seducer writes in his last entry. “I do not wish to be reminded of my relation to her; she has lost her fragrance.”

All this made “Either/Or” a succès de scandale: one reader observed, “I think no book has caused such a stir with the reading public since Rousseau placed his ‘Confessions’ on the altar.” But Kierkegaard’s method was the opposite of the one chosen by Rousseau, who said that when he appeared before God on Judgment Day he would present a copy of his “Confessions” and declare, “Thus have I acted; these were my thoughts; such was I.” For Kierkegaard, straightforward autobiography couldn’t do justice to the truth of his experience, which was full of ambiguity, self-division, and doubt.

Instead, he concocted a series of nested narratives, defying the reader to say where Kierkegaard himself can be found. The introduction to “Either/Or” recounts how the book’s “editor,” Victor Eremita, accidentally discovered a bundle of manuscripts in a secondhand desk. By the handwriting, he could tell that they were the work of two unknown authors; accordingly, the book is divided into two parts, attributed to “A” and “B.” Eremita even says that he is placing the author’s fee in an interest-bearing account for A or B to claim, should they ever appear.

The putative manuscripts encompass critical essays, the seduction diary, aphorisms, letters. Taken together, they illustrate the contrasting “life-views” of A and B, which Kierkegaard describes as the aesthetic versus the ethical. For A, life should be nothing but a series of interesting sensations. “How terrible is tedium—how terribly tedious,” he muses. The seducer’s diary shows how love is deformed when it is treated as just another trick for avoiding boredom. B is an older, married man who writes a series of letters to A chastising his frivolity. B argues that marriage represents not the death of romantic love but its fulfillment on a higher, more serious plane. “You talk so much of the erotic embrace, but what is it compared with the matrimonial!” he proclaims.

The title “Either/Or” implies that one must choose between these two ways of life, but that is just what Kierkegaard did not do. Whatever his readers may have imagined, he was not a cynical sensualist like A. He had courted Regine with the utmost propriety and was devastated by the end of their relationship. He never loved another woman, and when “Either/Or” was published he had two copies printed on vellum—“one for her, and one for me”—which he kept in a specially made cupboard.

But Kierkegaard could not become a contented husband like B. He left Regine, Carlisle argues, because marriage would mean sacrificing the freedom, the open-endedness, that he saw as the essence of an authentic life. “His life would be understood—it would be measured and judged—according to a well-established way of being in the world, shaped by a precise configuration of duties, customs, expectations,” Carlisle writes. Kierkegaard preferred to remain dizzily suspended over the abyss of his own freedom, the only position that allowed him to keep writing.

In a typically dialectical fashion—“dialectical” is one of Kierkegaard’s favorite words—he used this freedom to think about the nature of commitment. He believed that the most important commitment we can make is to God, and his work grew increasingly concerned with religious faith. Eight months after “Either/Or” appeared, Kierkegaard published “Fear and Trembling,” probably his best-known book today, which begins with the proposition that a human being becomes great “in proportion to the greatness of that which he loved.” There is no greater object of love than God, Kierkegaard writes, and the Bible’s most powerful example of what it means to love God is the story of Abraham’s attempted sacrifice of Isaac, which he subjects to a powerful and dramatic analysis.

When God commanded Abraham to take Isaac—“your son, your only son, whom you love,” the text emphasizes in Genesis 22—and slaughter him with a knife on top of Mt. Moriah, it was contrary to every natural feeling and ethical principle. It was even contrary to God’s own earlier promise that Abraham would become, through Isaac, the father of a great nation. Yet Abraham obeyed—and his reward was to see Isaac saved at the last minute, when an angel appeared and told him he had passed God’s test.

Because the story is so familiar, it is easy to glide past its transgressive implications. Imagine, Kierkegaard writes, that a Danish pastor in the nineteenth century made the sacrifice of Isaac the subject of a Sunday sermon, and one of his congregants was inspired to go home and murder his own son for the sake of God. If the pastor found out, he would surely go to the man’s house and exhort him not to do it—and this exhortation would be far more earnest and passionate than the original sermon, showing where his real conviction lay. Abraham had a kind of faith that even the most religious people lack: he believed that God had the power to suspend morality. More, he trusted that somehow God would make it possible for him to kill Isaac and still keep him, which is logically impossible. True faith, Kierkegaard insists, believes “by virtue of the absurd”—which is why almost no one has it.

The only reason we are able to praise Abraham for doing something that would horrify us in actuality is that we make excuses: Abraham was a great man, he lived a long time ago, things were somehow different for him than they would be for us. But Kierkegaard insists that there is no difference between the past and the present, between Abraham and you. The responsibility of choice—to believe or not to believe, to act or not to act—is always individual. “It is repugnant to me to do as so often is done, namely, to speak inhumanly about a great deed, as though some thousands of years were an immense distance,” he writes in “Fear and Trembling.” “I would rather speak humanly about it, as though it had occurred yesterday.”

During the next six years, Kierkegaard pursued the dialectic of belief through thousands of pages. His collected work in Danish fills twenty-eight volumes, almost all of it produced between 1843, the year of “Either/Or” and “Fear and Trembling,” and 1849, when “The Sickness Unto Death” appeared. Then he mostly stopped writing. The final part of “Philosopher of the Heart,” covering his last six years, reads almost like a coda. By the age of forty, Carlisle writes, Kierkegaard had become “a frail figure: more stooped and slender than ever, his hair thin, his face tired.”

He didn’t seem to miss his life of feverish productivity. In one of his last major books, the posthumously published “The Point of View for My Work as an Author,” Kierkegaard summarized the “movement” of his authorship as a journey away from cleverness and complexity. “Christianly, one does not proceed from the simple in order then to become interesting, witty, profound, a poet, a philosopher,” he writes. “No, it is just the opposite; here one begins and then becomes more and more simple.” The final simplicity is silence, and in his last years Kierkegaard truly earned the pseudonym under which he had published “Fear and Trembling,” Johannes de Silentio—John of the Silence.

When he became seriously ill, in 1855, he seemed content to die, even though he was only forty-two. The money he had inherited from his father was about to run out—he had spent much of it on the publication of his books—and he might well have felt that the timing was providential. Kierkegaard’s niece visited him in the hospital shortly before he died, and observed that “a feeling of victory was mixed in with the pain and the sadness.” One of the last things he wrote was a letter to his brother about the disposition of his estate: everything he owned was to go to Regine, “exactly as if I had been married to her.” ♦Published in the print edition of the May 11, 2020, issue, with the headline “The Abyss of Freedom.”

Adam Kirsch is a poet, a critic, and the author of, most recently, “Who Wants to Be a Jewish Writer?

==================================================

My cmnt: the following is from google Ai when asked if Kierkegaard was a Christian:

Yes, Søren Kierkegaard was a Christian, specifically a Lutheran Protestant. He was raised in a Pietist Lutheran family and his writings frequently engaged with Christian themes, ethics, and the nature of faith. While he was critical of organized religion, particularly the Danish Church of his time, his work was deeply rooted in Christian theology and focused on the individual’s subjective relationship with God.

Here’s a more detailed explanation:

- Religious Background:Kierkegaard was born into a deeply religious household. His father, Michael Pederson Kierkegaard, was a Lutheran Pietist, a religious movement that emphasized personal experience and devotion.

- Influence of his Father:Kierkegaard’s father instilled in him a profound sense of religious seriousness, though also a deep-seated melancholy due to personal experiences and a belief in a family curse.

- Key Theological Themes:Kierkegaard’s theological work explored Christian ethics, the relationship between the individual and God, and the nature of faith. He famously contrasted objective proofs of Christianity with the subjective, passionate nature of faith.

- Critique of the Church:While a Christian, Kierkegaard was a sharp critic of the established Danish Church, which he believed had become too formal and removed from genuine religious experience.

- Existentialist Philosophy:Kierkegaard is considered the first existentialist philosopher. His focus on individual existence, choice, and responsibility in the face of an absurd world is deeply intertwined with his Christian worldview.

My cmnt: the following is from google Ai when asked with Kierkegaard was an existentialist:

Yes, Søren Kierkegaard is widely regarded as the first existentialist philosopher. While the term “existentialism” wasn’t coined until the 20th century, his philosophical ideas laid the groundwork for the movement. He focused on individual existence, freedom, responsibility, and the subjective experience of life, all core tenets of existentialist thought.

Here’s why he’s considered an existentialist:

- Emphasis on Individual Existence:Kierkegaard’s philosophy centers on the individual’s experience and their unique relationship with the world, rather than abstract systems or universal truths.

- Freedom and Choice:He explored the concept of human freedom and the responsibility that comes with making choices, even in the face of uncertainty and anxiety.

- Subjectivity:Kierkegaard emphasized the importance of subjective experience and personal truth, contrasting this with objective, detached ways of knowing.

- Theistic Existentialism:While some existentialists are atheists, Kierkegaard’s existentialism was rooted in his Christian faith, exploring the individual’s relationship with God and the challenges of faith.

- Key Existentialist Themes:Kierkegaard’s works explore concepts like anxiety, despair, and the “leap of faith,” which are central to existentialist thought.

His influence on 20th-century existentialist thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger is widely acknowledged.

==========================================================

Soren Kierkegaard — The Father of Existentialism

A deep dive into the philosophy of the Christian father of Existentialism

The Living Philosophy – Nov 02, 2022 – website

Kierkegaard was by far the most profound thinker of the last century. Kierkegaard was a saint.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein

For all its critical analysis philosophy has not yet managed to root out its psychopaths. What do we have psychiatric diagnosis for? That grizzler Kierkegaard also belongs in this galere.

— Carl Jung, Personal letter to Arnold Kiinzli, 28 February 1943

Søren Kierkegaard is best known as the “Father of Existentialism”. But unlike many of his Existentialist peers from Nietzsche to Camus, Kierkegaard was not an atheist. He was a devout Christian.

But it was precisely in this faith that Kierkegaard’s Existentialism expressed itself. His attitude towards Christianity was surprisingly similar to Nietzsche’s. Like Nietzsche he had much love for Jesus and little respect for the Church with its priest-led herd. Disillusioned with this all-too-human institution there are two choices: atheism and mysticism. Kierkegaard chose the mystical path.

Across his career the core theme of Kierkegaard’s work is faith. And faith for Kierkegaard is above all a personal relationship with a personal God. Another central element of Kierkegaard’s philosophy is a preference for passion over reason. He saw faith as the “highest passion”. It was something you lived. It was something that required action rather than logic and reason.

The Church disgusted him by keeping its congregation like children. His works were all dedicated to “that single individual,” because it was only in the individual that the intense passion of faith could work itself out.

Kierkegaard’s work as a philosopher was to ignite the same passion for living faith in his readers. He designed an elaborate stylistic method he called “Indirect Communication”. This method used pseudonyms, and various stylistic devices to force readers to think for themselves. The many narrators in a single work contradicted each other. And so this style forced the responsibility back on the reader to think things through.

Kierkegaard’s philosophical model was Socrates. In his Master’s dissertation, Kierkegaard examined the Ancient Athenian philosopher’s use of ironic questioning. This Socratic irony forced his fellow citizens to think for themselves. Kierkegaard designed his Indirect Communication to do the same.

Like Socrates Kierkegaard wanted to awaken a passion for living philosophy in his readers. Both thinkers wanted their reader/listener to go beyond the shallow ways of “The Crowd”. They wanted them to become true individuals.

Kierkegaard saw himself as a Christian missionary in Christendom. His task was to convert members of “The Crowd” into true individuals of faith. This work of Kierkegaard is usually divided into three key phases: the First Authorship, the Second Authorship and his direct attack on the Church in the last year of his life.

The Making of a Philosopher

There have been few philosophers as fertile as Soren Kierkegaard. After finishing university in 1841 at the age of 28, Kierkegaard started his writing career in a very deliberate way. This first set of works — published between 1843 and 1846 — he called his “Authorship” (or in hindsight his First Authorship).

It began with his greatest masterpiece Either/Or in February 1843. Eight months later he published three books in one day. One of these books was Fear and Trembling — another one of his great masterpieces. The next June he published four books in a month. In total he wrote sixteen books in the space of three years.

Like Alexander Hamilton, Kierkegaard wrote like he was running out of time. And this is no coincidence. We can trace the origins of this prodigious writing career all the way back to the youth of his father. When Søren’s father Michael was a starving shepherd boy on the Jutland heath he cursed God.

And for the rest of his life, Kierkegaard Snr. was wracked with guilt. He passed this guilt onto his children. And he came to believe that because of his blasphemy, he would lose all his kids before the age of Jesus’s death at 33.

Søren grew up in the oppressive gloom of his father’s melancholy and he inherited his father’s guilt. The fact that his father had lost two wives and five children before Søren turned 21 didn’t help matters. On his 34th birthday Kierkegaard expressed his shock at being alive in his journal:

How strange that I have turned 34. It is utterly inconceivable to me. I was so sure that I would die before or on this birthday that I could actually be tempted to suppose that my birthday was erroneously recorded and that I will still die on my 34th

This shadow of impending death was the fire driving Kierkegaard’s creative output. But it was not the only one. The other major influence was his broken engagement to Regine Olsen. They first met in 1837 when Olsen was 15 and Kierkegaard 25. They were engaged in 1839 but within a year Søren called off the marriage.

The reason for this abrupt break was never explained.

In his journals we find mention of a terrible secret he was harbouring and couldn’t face telling her. Olsen put it down to his religious vocation. We could also put it down to an avoidant attachment style. Or if we were feeling more cynical we could pin it down to a question of money. Michael Kierkegaard had left his son an inheritance. This inheritance was enough to support Kierkegaard alone but not a wife and kids. And so it may have been then that Kierkegaard’s need for freedom and his writing aspirations tipped the scales towards going solo. The Either/Or may have been between the life of a writer and the life of a family man.

We don’t know the cause. But the combination of this failed engagement and death’s shadow proved to be a powerful cocktail for creativity.

The First Authorship

This first stage of Kierkegaard’s writing career saw the Dane write sixteen books in three years. This phase ended with the book Concluding Unscientific Postscript in 1846, just over two months shy of his 34th birthday.

The essence of this phase is best illustrated by Kierkegaard’s stages of life. This First Authorship explores three different value systems — three ways of being. Kierkegaard calls them the Aesthetic, the Ethical and the Religious stages.

The Aesthetic stage

The Aesthetic stage is the first of Kierkegaard’s three Stages on Life’s Way. The Aesthetic individual is one of the quintessential types of modernity. And it is probably more recognisable to us today than it was in Kierkegaard’s time.

The Aesthetic stage is associated with the nihilism of hedonism. If this is all there is then we’d best be making the most of it. This isn’t just the sensual hedonism of a Don Juan but the intellectual and cultural hedonism of the dandy or the bohemian.

There is an intellectual distance to the Aesthetic way of being. And this , as Kierkegaard tells us in Either/Or, is because for the Aesthete, “boredom is the root of all evil”. The motivation of the Aesthete is not a positive moving-towards pleasure. It’s a negative moving-away from boredom.

The life of the Aesthete is one distraction after another — another exhibition, another movie, another party, another rave. Whatever it is that keeps things moving. Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote that when “skating over thin ice, our safety is in our speed”.

This person has not yet committed to life. They value possibility over actual reality. They use irony, sarcasm and scepticism to keep life at a distance. It is a fundamentally egotistical way of being. By filling life with distraction — and keeping an ironic distance even from these distractions — the Aesthetic individual keeps life at bay.

The Ethical Stage

The Ethical is the second stage in Kierkegaard’s threefold Stages on Life’s Way. The self-centring Aesthetical stage of being gives way to the Ethical. This new stage connects into society. In Either/Or Kierkegaard uses marriage as the archetypal idea of this Ethical stage. Marriage demands that we relate to another individual in an open, intimate and honest way. And it also demands commitment. We have to enter into the world. No more staying aloof in the space of infinite opportunity. Marriage is a definitive step into life.

This is emblematic of the Ethical stage in general which is a call for us to enter into the world. The word Ethical in Kierkegaard is connected to Hegel’s idea of Sittlichkeit. These are the traditional morals of the society — basically the social norms. To be Ethical is to be good; it means following society’s tablets of good and evil.

These social norms justify our actions within the society. The measure of an action in the Ethical stage is how well it conforms to this tablet of values. These values are easily communicated and offer us clear ways of deciding whether an act is right or wrong.

The Ethical individual sees the Aesthetical life as selfish. The Aesthetical individual fails to acknowledge their social debt and their communal existence. They are living in a narcissistic fantasy land rather than living in the real world.

Nowhere is the Ethical ideal more unmistakable than in the advice of Jordan Peterson. He tells us to make our bed, to pick up a heavy burden, to carry our cross. Peterson’s brand of self-help is a bridge between the Aesthetical and the Ethical.

Thousands and thousands of people who have been shunted by the brunt of life’s meaningless and absurdity have found a new lease on life, a new tablet of values thanks to Jordan Peterson. In more ways than one, Peterson is a Kierkegaard for the 21st century.

The psychologist Peterson (in stark contrast to the culture warrior Peterson) encourages people to become responsible. He encourages them to take steps to improve their life and the lives of those around them. In short he encourages them to enter the Ethical Stage.

The Religious Stage

The final stage on Kierkegaard’s hierarchy is the Religious stage. The best way of illustrating this stage is the Biblical example of Abraham and Isaac which Kierkegaard explores in-depth in his second masterpiece Fear and Trembling.

For Kierkegaard, being religious is not about joining a local congregation. Faith is a central element of Kierkegaard’s thought. It is something we must live. The Bible was not the last word on faith. It’s not something that’s all worked out for us and we can set aside — that’s the prejudice for reason and logic speaking. Kierkegaard says that every individual must do the work of faith for themselves. And not just once but again and again throughout their life.

Faith is a choice we make as individuals and it is an excruciating choice. This choice is a massive burden of responsibility. On this choice hangs the individual’s eternal salvation or damnation. And this is where Kierkegaard talks about his famous idea of Anxiety.

Anxiety is the awareness of the titanic magnitude of this choice of faith. It’s a double-sided emotion. On the one hand you have the dreadful responsibility of choosing for eternity; on the flip side you have the exhilarating freedom of choosing for yourself. This choice happens in time — in a single moment. This moment is where time and eternity intersect as the individual through the choice creates a self that will be judged for eternity.

The Religious stage is beyond the Ethical stage. It transcends the Ethical stage. What we see in the story of Abraham is that faith requires us to go beyond the ethical and go straight to the source — to God. God for Kierkegaard is the ultimate source of ethics. And so when it comes down to deciding what is good and what is evil God has the final word.

And if he so chooses, God can suspend the ethical. This is what happens in the story of Abraham. God without any explanation, asks Abraham to kill his son Isaac. It’s an impossible, horrible choice for a father. It is also, as Kierkegaard tells us, an inexcusable action from the point of view of ethics and the Ethical stage. There is no sensible justification for Abraham’s action.

Now the obvious question is how do you know the voice in your head is God? How do you know you aren’t another deluded nutcase killing their child because of some voices in their head? Because there is no rational explanation that can justify faith, Kierkegaard says we cannot know. We must take a “leap of faith”. And that is why the title of the book on Abraham is Fear and Trembling. Because this is exactly what we are going to be feeling in a moment of faith. It is a cataclysmic crisis and this is the impossible choice that Kierkegaard is speaking to.

God cannot be held accountable to logic. The path of faith is antagonistic to the path of reason. They do not point the same way as Hegel claimed. They cannot be synthesised. We must choose. Kierkegaard says that we cannot believe by virtue of reason; the only way to believe is by virtue of the absurd. The belief of faith is an affront to reason.

Looking at the progression of the stages we can see a clear evolution. The Aesthetical stage focuses on the individual. The Ethical stage focuses on the community. And finally the Religious stage focuses on God. Each layer is nested in the greater reality of the next stage. We are connecting with higher and higher spheres in the hierarchy of Being.

Second Authorship

Kierkegaard had always intended to become a pastor after finishing his First Authorship. With the writing done he could knuckle down to the real work of his religious life.

But for some bizarre reason he picked a fight with a Copenhagen newspaper. Its name was “The Corsair” and it was famous for literary satire. Kierkegaard insulted the reputation of the paper and dared them to satirise him. And satirise him they did. For the next year Kierkegaard was the subject of vicious ridicule. They didn’t go after the works but after the man portraying him as the centre of the world, as a hunched man and this hunched figure on a woman’s back presumably Regine Olsen with a stick in his hand.

This attack devastated Kierkegaard. Wherever he went he was ruthlessly mocked. He gave up on his beloved walks through the city streets where he used to talk with people from all walks of life.

Because of all this, Kierkegaard postponed his quiet religious life a little longer and renewed his creative efforts. The attack by The Corsair was the impetus behind the Second Authorship as Regine Olsen and his father’s curse had driven the first.

This Second Authorship dropped the satire and parody (though not the pseudonyms). And with it Kierkegaard focused on the creation of positive Christian discourses.

Kierkegaard wrote the works of his Second Authorship between 1846 and 1855. It was different from the First Authorship in many ways. Unlike the first phase of his work, the contours of this second stage were not mapped out in advance. It was a far less prodigious phase. In two of these years 1852 and 1853 Kierkegaard produced nothing at all.

The shadow of The Corsair affair is everywhere in these later works. The isolated personal faith of the individual was the First Authorship’s centrepiece. But with this new phase Kierkegaard is thinking of the relationship between the true individual and the broader society. And he is also considering the nature of this broader society.

It began with a review of a novel called “The Two Ages”. Kierkegaard used this review to critique the Modern age and its steamrolling of the individual. This “sensible age, devoid of passion” was creating an indifferent and abstract public he called “The Crowd”.

Following this review was Works of Love. This book highlights the distinction between two Greek words for love: eros and agape. Eros or desire is a selfish form of love. Even if it isn’t self-centred it is still directed at an exclusionary We. This “We” is the collection of people we have a personal inclination towards whether they are lovers, friends or family.

In contrast to this selfish love there is agape. This form of love isn’t an inclination but a duty. It’s not a preferential love of the people we are fond of but a universal love. It is the love of the neighbour regardless of who they are. This is the love that Christ exemplified in the Gospels. This love is a spiritual duty rather than a psychological inclination. And it can only come to be as a gift from God rather than from the attraction between human beings.

Sickness Unto Death approaches the same theme of the individual and the society from a different angle. This masterpiece of the Second Authorship is about Despair. Despair is the opposite of faith. It is when we are faced with the Anxious choice and choose wrong. It’s choosing an inauthentic life rather than the life of the self (a theme that Jean-Paul Sartre picks up a century later with his idea of “Bad Faith”). Despair is the way of those who gain the world and lose their soul. Kierkegaard says the people who give in to despair “pawn themselves to the world” and he writes that:

“if you have lived in despair, then whatever else you won or lost, for you everything is lost, eternity does not acknowledge you”

The Kierkegaard of the Second Authorship sounds more and more like an Old Testament prophet. Like these ancient prophets he tries to call people back to true faith. He criticises the established religion as having lost its way. He warns the people about the wickedness of their society. He encourages them to align their lives with God and to change their ways.

From the review of The Two Ages and Works of Love to Sickness Unto Death and Practice of Christianity, Kierkegaard’s intensity gears up.

This increasingly sharp criticism reaches a shrill peak in the last year of Kierkegaard’s life. In this final phase Kierkegaard sets aside his elaborate method of Indirect Communication. And with the gloves off his attack on the Church and on Christendom reaches a fever pitch.

One of the bones Kierkegaard had to pick was political. He attacked the Church for being too connected to the State. He argued that this was creating perverse incentives that had nothing to do with being Christian in the Kierkegaardian sense.

On the religious side, Kierkegaard had many things to say. He believed that the popular conception of Christianity demanded too little of its adherents. He argued that congregations keep individuals like children since the individuals were disinclined to take initiative for their own relationship to God.

This soft Christianity clashed with Kierkegaard’s Old Testament prophet vibe. He wanted a more “offensive” Christianity. He wanted to address “the problem of becoming a Christian” head-on. This task of the individual stood in stark contrast to the “monstrous illusion we call Christendom”. Kierkegaard painted himself as a Christian missionary in Christendom.

And Christianity for the Existentialist Kierkegaard had always been “the individual, here, the single individual”. Christianity was being reduced to a fashionable tradition that the herd dipped into once a week. This stood in stark contrast to the Herculean struggle with eternity at stake in Kierkegaard’s Christianity.

This last phase of Kierkegaard’s work was published in various newspapers and a series of his own self-published pamphlets called The Moment. Before publishing the tenth issue of this pamphlet, Kierkegaard collapsed in the street. A few days later he was in hospital where just over a month later on the 11th of November 1855 he died from a form of tuberculosis.