JOHN CARNEY – 8 Jul 2025 – Breitbart

My cmnt: I have long thought that Superman represented the Jewish idea of who the Messiah should be to its creator Jerry Siegel. Superman comes from another world as a supernatural child to a childless couple who raise him to be the savior of mankind. He comes to a righteous nation America (i.e., Israel) in the throes of the Great Depression and despair due to an evil, democratic president-for-life whose every action results in more poverty and a longer depression. I think that this is a large part of Jerry Seinfeld’s sitcom always having a Superman character in the background of his apartment.

================================================

From Encyclopedia of Cleveland History – Case Western Reserve University

SUPERMAN, the popular comic book superhero, was created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster in 1933 while both attended GLENVILLE High School. Their creation became known worldwide, inspired numerous imitation superheroes, and brought fortune to many, but Siegel and Shuster enjoyed none of that fortune between 1949-75.

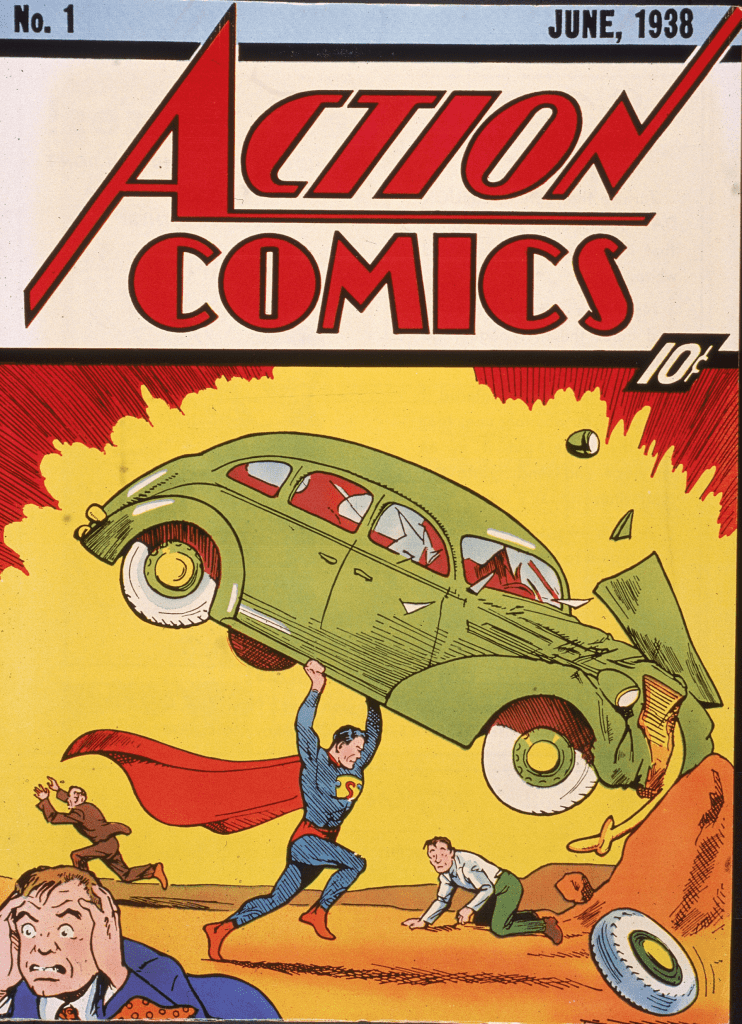

Native Clevelander Jerome “Jerry” Siegel (b. 17 Oct. 1914) was writing for the school newspaper, the Glenville Torch, when he created the Superman character. His collaborator, Toronto native Joe Shuster (10 July 1914-30 July 1992), worked up the initial drawings for the comic. Together they entered the new comic book business in 1936, not with their Superman character but by writing and drawing other adventure strips for New Fun Comics, Inc. In 1938 publisher Harry Donnenfeld paid $135 for their Superman strips, which first appeared in the premier issue of Action Comics in June 1938. The great popularity of the character soon led to Superman magazine, a syndicated newspaper comic strip (1939-67), a show on the Mutual Radio Network, animated cartoons (1941-43 and 1966-67), a 15-episode movie serial (1948), 2 feature films (1951), and a 104-episode television series in the 1950s. Superman also took center stage in the 1966 Broadway musical It’s a Bird . . . It’s a Plane . . . It’s Superman!

With Superman appearing everywhere, his creators slipped into obscurity and poverty. By signing a release form when they sold their strips to Donnenfeld, Siegel and Shuster had lost all rights to their character and perforce agreed to work exclusively for Donnenfeld for 10 years at $35 per page and half the net profit. When their contract ran out in 1948, they sued to recover the copyright; they received a $100,000 settlement but lost the court case, their jobs, and any further involvement with Superman comics. Siegel continued to work on various newspaper comics, but the legally blind Shuster had great difficulty finding work. By 1975, with public support from the Natl. Cartoonists Society and the Cartoonists Guild, they pressured Warner Communications, Inc., owner of Natl. Periodicals, for financial compensation. In Dec. 1975 the corporation agreed to pay each man $20,000 a year for the remainder of his life and to include their bylines on all future productions featuring Superman. Their creation with their names returned to the screen in the highly successful Warner Bros. film Superman (1978) and sequels Superman II (1981), Superman III (1983), and Superman IV (1987).

Dooley, Dennis and Gary Engle, eds. Superman at Fifty: The Persistence of a Legend (1987).

=====================================================

Superman: An American Raised in Kansas

When Superman first appeared in Action Comics #1 in 1938, America wasn’t grappling with border policy or multiculturalism. It was staring down something more existential: a collapse in fertility.

The Great Depression had driven the U.S. birthrate to historic lows. Total fertility had fallen to barely replacement level. Millions of American families had delayed marriage, postponed childbirth, or quietly resigned themselves to childlessness. In economic terms, the United States was confronting the early signs of a demographic recession—slower household formation, sagging demand for schools, and fears that a graying nation might not sustain its economic dynamism.

The decline in fertility had started decades earlier and continued through boom and bust, peacetime and war. By 1938, the trend appeared irreversible. Economists warned of stagnation. Schools were half-empty. America was getting older, slower, and less vigorous.

At the time, social scientists assumed the decline would continue indefinitely. The prevailing wisdom held that fertility would keep falling as societies modernized. Even leading economists and demographers believed America had entered a new phase of slow decline—aging, depopulating, and gradually surrendering its dynamism. Yet within a decade, the unexpected happened: birthrates surged. The Baby Boom rewrote America’s demographic future. And in retrospect, Superman looked less like a symbol of despair and more like a herald of rebirth.

Into this landscape fell a baby from the sky.

Cover illustration of the comic book Action Comics No. 1 featuring the first appearance of the character Superman in June 1938. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

A Childless Country Finds Its Hero

Superman’s origin story has been framed in recent decades as a tale of immigration. He came from another world, embraced American values, and found his place in a new society. And that’s the way James Gunn, the director of the latest Superman film, is spinning the story.

“We support ‘our people,’ we love our immigrants, and yes, Superman is an immigrant… if you don’t like that, then you are not American,” Gunn said.

But this is a retrospective overlay—a way of projecting contemporary cultural debates onto a much older and more intimate myth. A retcon, as they say in the comic book world.

Director James Gunn attends the “Superman” Fan Event on July 2, 2025, in London, England. (Jeff Spicer/Getty Images for Warner Bros)

In the original 1938 telling, Clark Kent wasn’t an outsider trying to assimilate. He was a boy raised from infancy by a childless American couple, the Kents, who lived in the moral center of the country. His powers were alien, but his values were thoroughly local. He didn’t adopt American ideals later in life—he was shaped by them from his very first step.

He arrives as a baby—a foundling in the heart of Kansas. The Kents didn’t take him in to make a point about migration. They took him in because they had no children of their own—and suddenly, one was given to them. They raised him right. They taught him restraint, justice, humility. And because of their love and discipline, he became the protector of the American way of life.

This matters, because it places Superman in a different symbolic category. He is not a metaphor for migration. He is an emblem of providential arrival, of unexpected parenthood, and of the power of family formation to preserve civilization. He appears at the very moment when many Americans were quietly beginning to wonder whether the future had room for children at all.

His story is simple: a boy is found in a field by people who thought they’d never be parents. They take him in. They raise him right. And because of their love and discipline and faith in this strange child, he becomes the protector of the world.

And he arrives just when Americans were beginning to fear they might run out of children—just as they feared their economy had run out of steam. He resonated with readers as a symbol of hope reborn at a time of economic and demographic despair. Just a decade later, American prosperity and fertility were literally reborn as the Baby Boomignited the sort of heroic population growth that had been written off as impossible.

Superman: A Hero for Our Demographically Challenged Times

This resonates more than ever today. Fertility in the United States has fallen again—below 1.6 children per woman, far beneath the level needed to sustain population without immigration. Economists worry about shrinking workforces, collapsing entitlement ratios, and the long-term stagnation of innovation and consumption. Countries like Japan and South Korea have already entered demographic death spirals. Europe is not far behind.

America, too, is running out of children.

That’s why it’s worth recovering the original meaning of Superman. In a time when biological parenthood was slipping out of reach for many, his arrival was not political—it was redemptive.

The old phrase says children are a gift. Superman’s story doesn’t just affirm that. It embodies it. He isn’t the product of national policy or social theory. He is what happens when two ordinary people say yes to the child in front of them.

If there’s a lesson here for policymakers, it’s not to double down on slogans or symbolism. It’s to recognize that the real path to national renewal begins, as it did in that Kansas cornfield, with the courage to raise a child.