by Lane Scott – Fall 2024 – Claremont Review of Books

My cmnt: This column is worth the read. The main point of the writer is that certain religious communities (i.e., my Yazidi next door neighbors, Utah Mormons, devout Catholics, conservative Evangelical congregations, etc.) are and have been bucking the trend of small or childless families and these mothers are happier, more fulfilled and at peace than their “career” women counterparts.

Modernity is no place for children. Every advanced civilization on earth is failing to replace itself. As developing nations approach prosperity and freedom, they too begin failing to reproduce. The United States had a total fertility rate of 2.1 in 2007. That number dropped to 1.7 in 2019 and is approaching 1.6 post-pandemic. It’s not unusual for fertility rates to dip momentarily after an economic crisis, but it’s deeply troubling that birth rates in America never recovered after the Great Recession.

One of the best chapters in Family Unfriendly: How Our Culture Made Raising Kids Much Harder Than It Needs to Be highlights a few places, like Israel and Utah, where high fertility has survived advanced development. Author Timothy P. Carney, a columnist for The Washington Examiner and an American Enterprise Institute fellow, observes that parents tend to prioritize having one spouse at home full-time in areas where deep faith and larger families are the norm. This creates a distinctive community ethos and allows a different type of childhood for the kids.

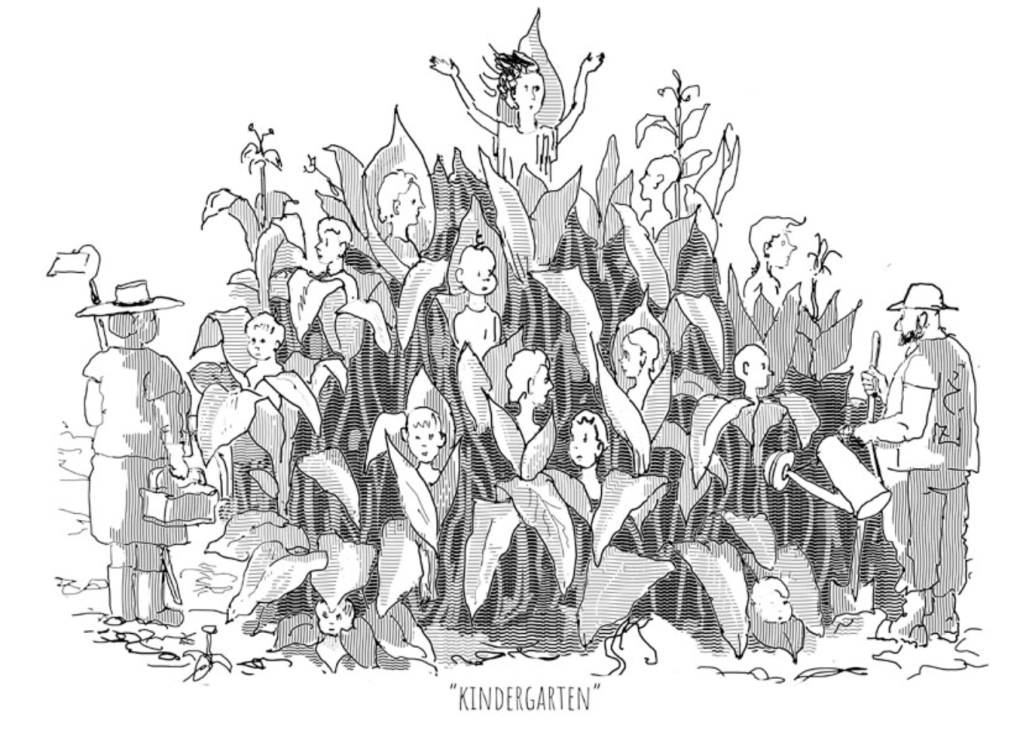

Carney argues that stay-at-home parenting affords children the luxury of relaxed adult supervision. America’s nostalgic ideal of childhood—“Come home when the streetlights come on”—requires a parent to facilitate it. By contrast, childcare institutions instill the expectation that children are to be closely supervised, their activities coordinated and planned, every moment of every day. Family Unfriendly makes a convincing case that the now-standard American childhood is detrimental to kids and downright torturous for adults.

***

In the fall of 2000 I found myself sitting in a garden in Ojai, California. A freshman at Thomas Aquinas College, I was neither Catholic nor interested in having children. But one of my professors had invited several students over for a large dinner party at his home—there must have been well over 70 guests. In his garden that evening, his eleven children hurried around visiting, grabbing extra chairs, making jokes, and laughing with the college students. Their lovely mother, relaxed, sat chatting with guests as her children set out dishes of food. As evening drew to dusk, the warm California temperatures fell swiftly. Approximately two seconds before I realized I was cold, one of the older daughters quietly wrapped her sweater across my bare shoulders.

Modern American life offers wealth, achievement, entertainment, and distraction. But it does not sustain. The kind of sorcery on display that night in the garden—the anticipation and fulfillment of the spiritual, physical, and intellectual needs of so many different humans—was nothing short of counter-cultural. My God, I thought, this is good. This I must have.

Carney’s high-fertility communities are perhaps most remarkable in what they do for outsiders. Even the secular inhabitants who simply live adjacent to these religious communities attain a much higher fertility rate. The pro-child culture appears to rub off on people, resetting the default fertility level higher for nonbelievers, too. If such cross-cultural pollination is possible at scale, then Carney has stumbled upon a real glimmer of hope.

The stakes are high, and public policy attempts to increase fertility have universally failed. Even the most generous cash payments to parents create only a temporary blip in fertility before birth rates plummet back below replacement levels. After decades of pro-growth economic policies in places like Singapore, South Korea, Europe, and Australia, we still do not have any success stories.

Underneath all his facts on modern demographic collapse, one suspects Carney is looking to ask a more pointed question: What happened to the professional mothers? That is, where are the mothers who don’t just try to squeeze in a kid or two before hurrying back to an effectively childfree existence—who instead welcome the change that children bring to their daily lives?

***

It’s an uncomfortable question. In lieu of asking it outright, Carney lays out every fertility statistic known to man in a kind of paint-by-numbers exercise. Thus he reveals, obliquely, the obvious center of the fertility crisis: a big, empty space where a matriarch used to be. America has fewer children and families because we lack the kind of women who cultivated and tilled the kinds of neighborhoods, volunteer associations, and civic life that created suitable ground for families to thrive.

Carney is careful to avoid discussing immigration and the cultural disintegration brought about by exalting diversity above all other social goods. Yet one cannot but notice that the majority of his complaints about modern family life—travel-team sports, the cost of housing and schooling, our unwalkable cities and suburbs, and incessant adult supervision of children—look a lot like parents working overtime to create distance between their kids and much of American society. This seems potentially related to the low social trust and mutual ethnic suspicion fostered by reckless importation of foreign populations without heed to their gradual assimilation.

It is politically unpopular to state that taxpayer money cannot buy the type of community or culture that produces ideal childhoods and therefore makes motherhood attractive. But that’s precisely what the numbers reveal. The majority of American mothers do not want subsidized childcare; they want to do it themselves. People do not want a government simulation of a community; they want communities. The biggest takeaway from Family Unfriendly is that American childhood doesn’t look like it is supposed to anymore, so American women are opting out.

It would help on the margins if those who are already mothers could find it in their hearts to have just one more. But the real deficit is with the “nones.” American mothers actually have slightly larger families on average than they did in the 1980s. The biggest drop in American fertility comes from women who will never have any children at all. From 2007 to 2019, first births dropped by 21%. Only half of American women in their late 20s have children. In 1975, it was 70%.

Carney inadvertently reveals the secret to a family-friendly society by recounting a hilarious conversation he shared with a professional woman of a certain age. Carney—father of six children—finds himself on a week-long escape to the Berkshires to finish writing his book. There he engages in conversation with an older feminist woman, who asks Carney whether his wife will also be getting a week off from family life to pursue her interests? Carney assures us that his wife is given breaks from family life all the time. Upon further review, however, he recalls that his wife only ever uses her “breaks” to babysit her sister’s kids, to nanny for newborn twins, or to soothe and counsel girlfriends who are struggling. In other words, Mrs. Carney spends all her free time building community. Carney assures readers these are simply his wife’s preferences. Yet it’s hard not to chuckle at the thought of this father-of-many on holiday to pen a book which might have been alternatively titled Wow! My Wife Is Wonderful and Yours Should Be Too: How to Solve the Fertility Crisis in America. Carney’s beloved Katie is really doing some heavy lifting off-page.

Which is, of course, the point. Katie Carney has dedicated her life to doing what it takes to make childhood lovely again in America for her family and friends. Her husband observes this and wants to pass the secret sauce along to everyone else. In lieu of government-issued Katie Carneys, however, the rest of us have got to figure out how to inspire more women to become cultivators of human society.

***

What inspires women to defy cultural trends and have large families? Catherine Pakaluk, an associate professor of social research and economic thought at the Catholic University of America, has written the perfect book to investigate. Hannah’s Children: The Women Quietly Defying the Birth Dearth features a series of interviews with college-educated women who have five or more children. Pakaluk’s treatise is delightful. It helps to have an economics background, as she does, when leafing through reams of fertility statistics. Her experience as a teacher—and as a mother of eight children—is also a great gift to the reader. Her clarifications and illustrations are so subtle that I found myself nearly fooled into thinking I had retained my stats and probability chops from my grad school days, all by myself.

The most intriguing element of Pakaluk’s study is her application of both rational choice theory and cost-benefit analysis to considerations beyond the bounds of this mortal coil. It’s rarely taken into account quantitatively, but the reality is that religious women do in fact choose to plot the costs and benefits of children on an immortal plane. “Women’s time is the biggest input into childbearing; if that input has become more expensive in terms of opportunity costs, only those with an extraordinarily high demand for children will still have children.” These costs are significantly offset by divine benefits for those who believe in them, as the 55 mothers Pakaluk interviewed universally attest. “If you want to find a policy angle to improve the birth rate,” Pakaluk concludes, “expanding the scope for religion in people’s lives is the most viable path…. Religion is the best family policy.”

***

Pakaluk’s appeal to heaven is a reasonable conclusion for a demographer to reach. The technological and social upheavals of the last hundred years have drastically changed women’s calculus for life decisions. Because they have more career possibilities arrayed before them, they now give up more by raising kids. Meanwhile, affordable and reliable contraception allows young women to place children on equal footing with every other good: something they hope to get around to at some point. What the birth dearth reveals, though, is that children are a jealous good. If deferred too long, they may never come at all. We simply cannot offer financial rewards or government benefits sufficient to erase the career and lifestyle rewards women must forgo to have children in the modern world. But as the mothers in Hannah’s Children explain, the heavy burdens of motherhood are nothing in comparison to the divine joy children offer. Is it crazy to conduct a cost-benefit analysis with a heavenly thumb on the scale?

Hannah’s Children reveals why economic and political incentives to higher fertility are doomed to fail. Children demand sacrifice, of a kind that cannot be repaid with money. It isn’t like a two-year master’s program or a nine-month sabbatical. It is more akin to men offering themselves up for their country in war. It is noble, divine—the most honorable sacrifice anyone can give. Once a woman has a child, she will never again enjoy autonomy. A part of her body—or, really, her soul—is now alive and existing outside of herself. There is no turning back from that moment, no relief from that responsibility. The only commensurate repayment is honor and praise. When we set up petty cash payments and tax credits designed to entice women to have children, all we do is cheapen the nature of their sacrifice in the minds of the public.

Life’s most meaningful relationships have cruel expiration dates. Young people are often confused about how to rank desirable goods, so they end up prioritizing the things they want by default, based on proximity or perceived ease of attainment. This is a profound mistake. Young adulthood is the best time to be courageous in war, to make lifelong friends, to fall in love, and to have children. Youth is a serious business, and we do a disservice to young people by failing to tell them that. Instead of asking ourselves which things we want out of life or would enjoy having, we should try to determine which things we simply cannot live without.

The man I would eventually marry once asked me if I had any hobbies or interests. “Well…tycoonery,” I offered. A poor country kid, I had rarely met with a bauble or passion that didn’t delight. I wanted it all. After that September night in the Ojai garden, however, this calculation changed. I still wanted everything I could get out of life—career, honor, riches. But now I had to have a garden with a large Catholic family of my own. I craved many things. But this one thing, I could not do without.

Lane Scott is a writer living in Angels Camp, California.

Leave a comment