My cmnt: When I read his book several decades ago this is what I remember taking away. Penrose maintains that an actual infinite cannot exist in the physical universe. He uses the illustration of a library with an infinite number of both red and black books. If someone removed one red book from this library would there now be more black books than red? Physically and logically there must be but mathematically there cannot be as both sets of books are infinite and therefore can neither be added to nor taken from in anyway that will affect the total number of books. His point being that an actual infinite is physically impossible. And what he derives from this understanding is that our minds can easily conceive of infinity and eternality which must in fact exist for anything to exist at all (i.e., God or an eternal particle) and given what we actually observe in the universe God is the more reasonable answer. Therefore our minds are not mere machines contained within a finite universe because they need infinities or at least the concept of infinity in order to perform higher mathematics and to understand the universe and therefore our minds transcend the physical brains they inhabit and are not mere computers made of meat.

For the past two years, Stephen Hawking’s A Short History of Time has been ensconced on the best-seller list, a…

by Jeffrey Marsh – June 1990 – Science, nature and technology

… rather unusual place for a serious work that deals with a scientific topic. Recently it was joined for a bit by a considerably longer book by Roger Penrose, the equally eminent mathematical physicist whose work on black holes provided the original inspiration for Hawking’s Ph.D. thesis. And although it might seem that no subject could range farther than Hawking’s—the creation and ultimate fate of the universe—Penrose has chosen one even more ambitious. He addresses here nothing less than the question of the nature of the human mind, approaching it by way of a broad array of scientific disciplines, among them, surprisingly, cosmology.

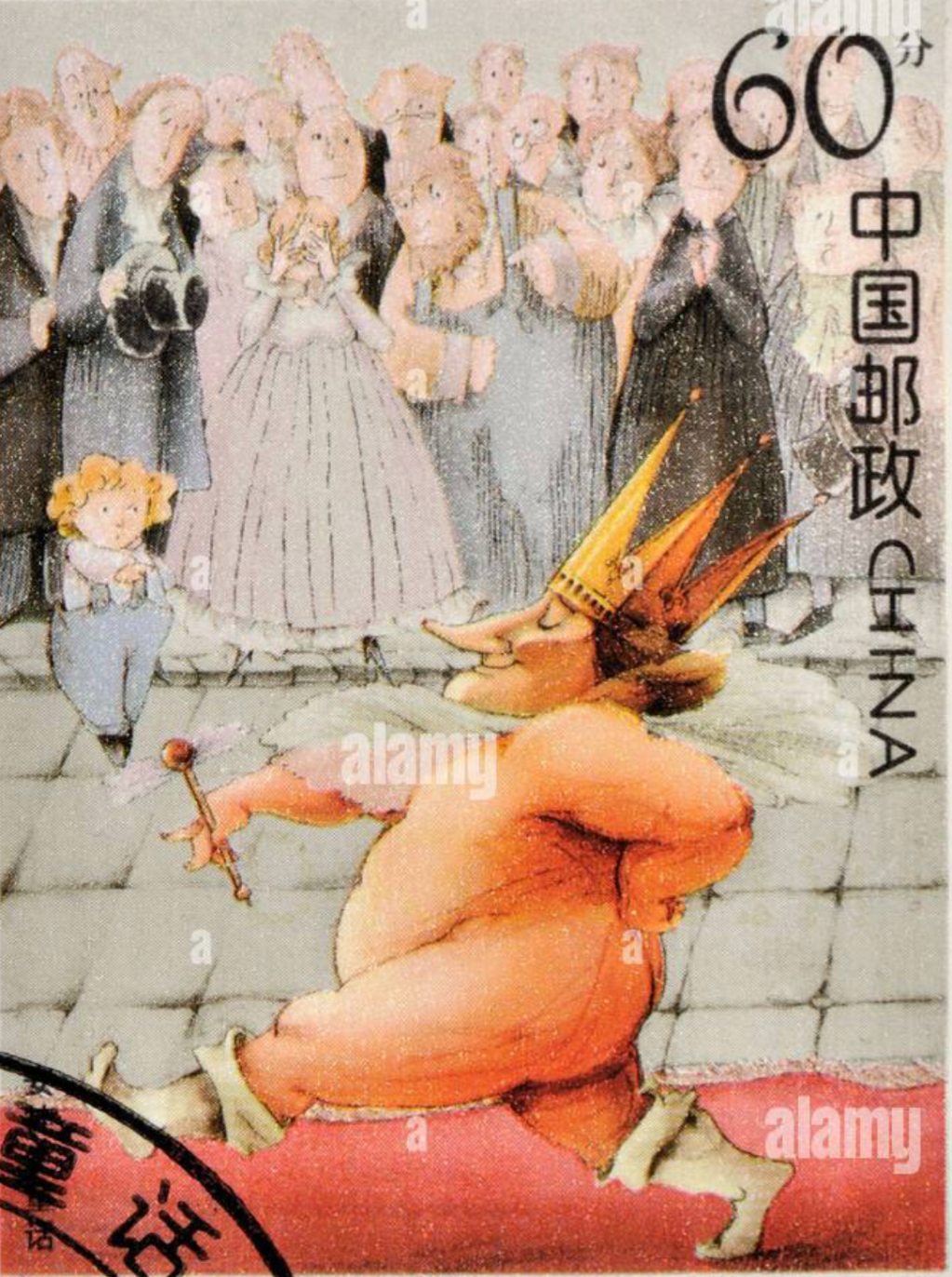

The central issue of The Emperor’s New Mind is whether the human mind is simply a highly complex computer. If that is the case, then it should be possible in principle, as Alan Turing suggested some forty years ago, to construct a computer whose workings so closely resemble human thought that it will respond to any question put to it with an answer indistinguishable from one that might be given by a human. Yet, while some computers have indeed been programmed to mimic quite convincingly certain kinds of dialogue—in particular, and rather bizarrely, conversations between psychotherapists and their disturbed patients—no machine constructed to date has shown anything approaching the capability to pass the Turing intelligence test. Still, computers have been around for only forty or fifty years, and many physical scientists and not a few philosophers believe that eventually it will be possible to construct (or, more precisely, to program) one that will do so.

Penrose is emphatically not an adherent of that school of thought. In The Emperor’s New Mind, he explains why he believes that the principles governing the operations of computers cannot adequately model the workings of the mind. Instead, he proposes the more sweeping and controversial thesis that human thought processes transcend the laws of physics and chemistry currently known. In the course of advancing this proposition, he explores the theories of computer science as well as mathematical logic, classical physics and relativity, quantum mechanics and neurophysiology.

_____________

Penrose begins with a discussion of the nature of computers and the way they work, summarizing the ideas of Turing, who in the 1930’s and 40’s described an idealized computer, the so-called Turing machine. Such a machine tackles complex mathematical problems by following a systematic set of instructions (or algorithms), performing one step at a time until the answer emerges and the machine stops. As a mathematician, Turing was interested in the fundamental question of whether there existed in theory a universal algorithm—a recipe by which a computer could solve any mathematical problem. He answered his question in the negative, in an elegant argument that used reasoning similar to that introduced earlier by Kurt Gödel in his famous theorem about the unprovability of some mathematical statements whose truth might nevertheless be apparent to an observer outside the closed logical system. So, asks Penrose, how could the human brain be simply a computer, programmed to follow set algorithms, if it can answer questions unsolvable by following a prescribed set of rules?

As an especially gifted and creative mathematician, Penrose is well aware of the reality of intuition, and of the fact that the systematic logical structure of theorems and proofs that mathematicians use to present their results is far removed from the creative flash of insight by which those results are actually derived. He suggests that there is a real world of mathematical truth that is not captured by formalism, and that is the world in which the human mind is at home.

To Penrose, moreover, the ideas that mathematicians create as they extend previously existing concepts seem to bear an uncanny relation to the realest of real worlds, namely, the physical universe. For example, over the course of millennia mathematicians have expanded the concept of number, to which children are introduced in the most primitive sense when they are taught to count. Seeking to generalize the concept so that every arithmetical problem has a meaningful solution, mathematical thinkers have broadened it to include negative, rational, irrational, and transcendental numbers, eventually making the system complete by inventing complex numbers. These are strange hybrids that pair real numbers, in all their prosaic solidity, with imaginary numbers based on the invented and apparently absurd idea of taking the square root of a negative number. Yet it turns out that complex numbers are needed to describe the behavior of real objects in the world.

They are especially needed for the theory of relativity, which completed classical physics by uniting space with time and matter with energy, and they are absolutely essential to quantum mechanics. The paradoxical results of quantum mechanics, far from what would be predicted by the common sense instilled by experience in the everyday world, are nevertheless well proved by experiments in the world of submicroscopic particles and are utilized in the amazing electronic devices that have proliferated during the 20th century.

_____________

The theory of quantum mechanics is fully established. Penrose himself assigns it, along with Euclidean geometry, to the category he terms SUPERB (the eccentric use of capitalization is his own). But he is troubled by some fundamental gaps in our understanding of it—in particular, the famous question of how an isolated physical system which goes along quite happily on its own as a mixture of mutually exclusive possible states is somehow reduced to one definite but unpredictable state when someone observes it, and then how repeated observation produces a distribution of states that occur with a predictable probability. Perhaps even more puzzling, it appears that objects far too distant from each other to communicate in the manner prescribed by relativity (another SUPERB theory) seem to have instantaneous knowledge of each other’s state.

Many attempts have been made to explain these paradoxes, the most imaginative being that the world is continuously splitting into an ever-growing series of different parallel worlds, but Penrose finds none of them logically satisfactory. He is also troubled by the problem of cosmology. The current state of the universe implies that creation occurred by means of a “big bang,” but on the basis of the second law of thermodynamics the probability of that incredibly hot and dense state ever occurring is inconceivably minute.

The solution to this problem, as well as to those raised by quantum mechanics, Penrose feels, must come from a synthesis of quantum mechanics and gravitation. In particular, such a synthesis would explain how localized phenomena somehow carry within themselves some “knowledge” of the state of the universe at large. It would also, he hopes, show how the mind is able to think creatively, jumping from isolated thoughts dealing with disparate matters to a more general understanding. And finally such a synthesis would help to explain the phenomenon of consciousness that enables a mind to decide what to do and to communicate with other minds.

_____________

In slightly over 450 pages Penrose covers a wide range of exceedingly difficult topics. These are frequently mathematical in nature, and many of the points he makes are subtle, but the book is written in a conversational and highly individualistic style. Penrose’s enthusiasm leads him into lengthy digressions that illustrate many of his particular interests and original contributions to a variety of scientific and technical fields. While he sometimes goes into considerably more detail than some readers may be prepared for, the exercise serves as an excellent demonstration of his thesis that the mind is far more than a computing device. As a thoroughgoing scientist, Penrose never refers to the concept of revelation; but as he describes the relationship between the human mind and the underlying reality of the universe, that is inevitably the word that springs to mind.

Leave a comment