by John J. DiIulio, Jr. – Spring 2024 – Claremont Review of Books

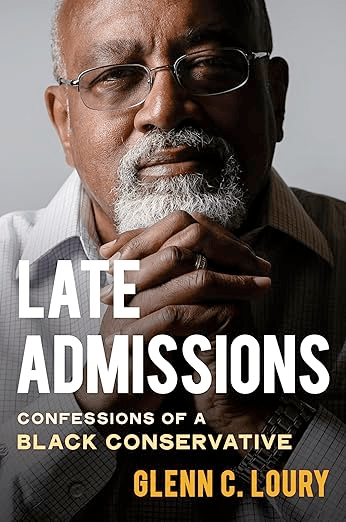

In 1982, Glenn C. Loury—who will turn 76 in September this year – but charmingly refers to himself as “aging”—became Harvard’s first tenured African-American professor of economics. He is a world-class economic theorist, a monumentally impressive public intellectual, and a now-faithful father of five—having overcome decades-long sex and drug addictions. In Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative, Loury looks back at his life and legacy, his tragedies and triumphs.

Loury prefaces this memoir with an emphatic promise to reveal things about himself that “no one would want anybody to think was true of them.” He delivers on that promise, inviting readers to “search out my contradictions and too-convenient narrative contrivances.”

I did, but full disclosure: although I have not seen him in person or spoken to him for a little more than two decades, I knew him personally. In the late 1980s through the early 2000s, we had several friends and acquaintances in common on Harvard’s faculty, among prominent conservative public intellectuals, and within Boston’s black Pentecostal clergy. We published with many of the same magazines and journals and debated each other in print. In 2001, I commissioned him to write the foreword to a Brookings Institution volume on religion in America that I co-edited with E.J. Dionne. That was my last interaction with him, but I always liked, admired, and, at times, prayed for him.

***

Loury tells his story forthrightly, often in the graphic language that is heard regularly on the rough streets of his native South Side Chicago. At one point while he was growing up, he, his mother, and his little half-sister lived in a small apartment beside a six-bedroom, three-car garage home owned by his mother’s sister, Auntie Eloise. The house also accommodated four of Loury’s cousins. Eloise’s husband, Uncle Moonie, owned a barber shop where he also sold a little reefer. Glenn shined shoes and ran errands for him there. The childless couple took Glenn in after he had moved many times and attended five different schools by fifth grade.

Auntie was a quintessential black church lady of her day. She was neither too quick to judge nor too slow to forgive. She had a working-class moral compass and middle- or upper-class aspirations for her nieces and nephews. Eloise fretted that her sister’s failed marriages and other poor choices might pull Glenn to the wrong side of the “line between nascent bourgeois respectability and hopeless poverty.” She offered her heart, her home, her money, and her no-nonsense readiness to “yank” him “back to the right side,” where her prayers were.

Not, mind you, that young Glenn was ever fatherless or penniless. Everett Lowry once had his last name misspelled Loury by a teacher and just left it that way. Everett had an accounting degree; he had been to law school. After divorcing Glenn’s mother, Everett always lived close enough to Auntie Eloise’s house to take his son to White Sox games and on vacations. When Glenn began his “science boot camp” studies at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Everett handed him $1,000 (the equivalent of about $10,000 today).

***

Glenn began high school at age 12, an awkward math whiz nicknamed “Black Walrus” by his cousin Jimmy in mockery of his chubby frame. He graduated as a “valedictorian and a virgin,” but also determined that senior prom night should be the night. Convinced that a car’s backseat was the place but unable to borrow a car, he stole one and got arrested. He got off easy, and the charges were expunged. But he missed the prom. Everett, who preached but did not himself always practice self-discipline, lambasted Glenn for acting like his father’s half-brother, Uncle Gerald—“a drunk and a f-ckup.”

Ah, but his Uncle Adlert would give Glenn an “A” for effort. Adlert had told the boy that “life’s goal” was to “get as much p-ssy as you can,” and Glenn “took his advice quite seriously.” For decades, both when he was single and when he was married, he fed his sex addiction in ways that disrespected and devastated his wives; upset his neglected (and, in one case, barely acknowledged) children; embarrassed and saddened his friends, relatives, and employers; and compounded his drug addiction.

Still, in 1982 Loury arrived at Harvard in silks. Having already done seminal work, he was on the fast track to the pinnacle of the economics profession. But he felt he was “starting to choke” and would soon be found out “for the fraud I was now beginning to suspect I might be.” An old mentor from MIT tried recruiting Loury away from Harvard, but confided: “You wouldn’t be getting this offer if you weren’t black.”

So, when he had the chance to recast himself as more a public intellectual than an economist’s economist, he took it. After meeting Marty Peretz, publisher of The New Republic, he drafted a provocative essay on racial inequality (“A New American Dilemma”) that seemed almost calculated to make conservatives cheer and liberals weep. In fact, it literally did the latter. In the summer of 1984, he gave a presentation based on the draft essay, sharply criticizing the narrow intellectual confines of the black community, at a conference featuring a who’s who of black leaders. Sitting right next to him was Coretta Scott King, wife of the late Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. She cried, and the tears were “her only commentary.” “I want to offer her comfort,” thought Loury, “but…I fear that if we don’t get it right, we will find ourselves dealing with these very same issues two or three generations down the line.”

***

Soon, he was aligned “with the Neocons, the Reaganites,” and others on the right. Many in “black leadership” took his “conservative turn as a betrayal.” His next piece, “The Moral Quandary of the Black Community,” was for the neoconservative flagship journal The Public Interest. “Black people,” he insisted, “needed to take responsibility for their lives…. Real solutions would have to come from inside.”

Yet critics might have instructed the sick physician to heal himself. In 1987, he was caught in the first of several public scandals. While he was being vetted for a position in the U.S. Department of Education, he was arrested by police in Boston after a mistress claimed he had assaulted her. The department’s leader, William J. Bennett, and his aide, Bill Kristol, stood by him. Several Harvard Law School colleagues rallied to him. The woman stopped cooperating with prosecutors, and the charges were dropped. But Loury withdrew his candidacy—not because of the adverse publicity, and not because he suddenly reckoned he was not up to the job. Rather, he reasoned that if he was confirmed and served in government, he “would have to stop f-cking around.” And he had less than no intention of stopping.

A prostitute who introduced him to “little white crystals” lit his road to a crack cocaine addiction. While on a sex binge, he was robbed at gunpoint by a “skinny, desperate looking man” who demanded crack or cash. Disgraces like this were a gift to the left-wing critics who derided him as a token and a tool of white conservatives. They took perverse satisfaction in depicting him as a hypocrite, a “feckless libertine” who “prescribed Victorian morals” for the black underclass while exempting himself. Each time he survived, though, his “insufferable” egotism and narcissism (“the enemy within”) prompted him to take it as proof that he was becoming “Master of the Universe.” Nobody else, said the enemy, could pull off the life of an eminent professor by day while doing what he did at night.

Late Admissions casts light on certain important realities that most life-long members of the upper-middle class can be forgiven for missing or misunderstanding. One of them is that internal divides cut across all races within the lower classes. In neighborhoods like South Side Chicago—or South Philly, where I grew up—being “working-class” means you finished or almost finished high school. You at least gestured toward going to church on Sundays. And you “answered the bell” for work on weekdays, no matter how deep in the hole or how hungover you were.

But alongside these working-class folks, within the same communities, were what in Philly we used to call the “white trash” and “water rats”: the ones who just marked time or quit school, got high, slept around, never got married, and begged relatives, friends, or neighbors for money (or cigarettes, or use of a car, or other things). By the same token, an otherwise solidly working-class black kid like Loury could and did rub shoulders with more troubled kids: a Little League pal who died of a heroin overdose at 18; a cousin who would beg his mother for food, get it, and then steal from her anyway; a “grade-school nemesis” who shot a cop and “caught a life sentence.”

When working-class-bred boys, whether black or white, go on to become upper-class men, they often look back with nostalgia on their old family, friends, and acquaintances. They want, at least occasionally, to mingle again with the “white trash” or “black underclass” folks who still remain somewhere in their lives’ outer orbits. In Loury’s case, this craving for connection careened into existential questioning. Did he make the right choice by climbing up to middle- and upper-class respectability? Can a newcomer ever really be anything other than an impostor? These cascading self-doubts metastasized into destructive behavior, leaving Loury, a Harvard professor by day, courting casual sexual encounters and smoking crack by night.

***

As Loury explains, he could fittingly be called “conservative” from about the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, and again from roughly 2013 to the present. But from 1997 to 2012, “anti-conservative” would be a more apt descriptor. He synopsizes his break with the Right by recounting his reaction to each of three books: The Bell Curve (1994) by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The End of Racism (1995) by Dinesh D’Souza, and America in Black and White (1997) by Abigail and Stephan Thernstrom.

As Loury tells it, in The Bell Curve Murray and Herrnstein reckoned that “it was the fate of black Americans, due to a low average level of cognitive ability, to remain at the bottom of the heap.” Loury was incensed when neither Commentary magazine nor the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) would serve as platforms on which he could debate Murray (Herrnstein having died). For years thereafter, Loury took “potshots” at Murray and “mocked what I took to be his lack of technical facility.”

Today he admits that Murray, whom he considers a friend, was wrongly “pilloried as a racist and a eugenicist.” Still, what troubled Loury most was how many conservatives took the book’s core findings at face value but came away without long faces. Here, after all, was a book claiming that no conceivable mix of public policy responses can improve substantially the life prospects of tens of millions of your fellow citizens—certainly not anytime soon, and maybe never. Yet, as Loury experienced it, “the mood on the right was one of triumph.” I felt it at the time, too: the Right was delighted, and the Left was in denial.

Likewise, in a review for The Weekly Standard, Loury argued that The End of Racism mangled the history of slavery, overdramatized the (already sufficiently dramatic) dysfunctions of black life in the inner cities, and evinced little interest in solving rather than condemning black people’s social problems. To protest AEI’s support for the book, Loury and black conservative civil rights leader Robert Woodson resigned from its board. But the most personally painful book of the three was America in Black and White, by Loury’s dear friends the Thernstroms. Writing in The Atlantic, a liberal-leaning publication then as now, he condemned the book’s “figment of the pigment” thesis: the notion that extreme rates of black poverty and other socioeconomic ills had zero to do with racism.

***

Many conservatives reacted with scorn and horror to Loury’s leftward swerve. But there was one notable exception. James Q. Wilson—the most eminent political scientist and influential conservative public intellectual of his era—continued to treat Loury as a friend, albeit one who had taken to spouting “arrant nonsense” (as he described it to me) on incarceration and some other matters. Wilson’s message about Loury to other conservatives was, “Don’t pile on.” He himself never did.

For example, in 2008 Loury’s Tanner Lectures, which he had delivered at Stanford University the year before, were published as a slim MIT Press book, Race, Incarceration, and American Values on “the brutal facts about punishment in today’s America.” In truth the book was more rhetorical than analytical. As he confesses in Late Admissions, Loury “went all in on incarceration” because there was “no blacker project than criticizing America’s prisons,” and it was easy for him to become “a voice of alarm and protest.” Wilson and I, along with several black thinkers, were entreated by certain conservative think tanks and publications to seize the moment and crush Loury beneath a fact-based, take-no-prisoners tome. Wilson declined. He was too busy, it wasn’t his style, and, as he confided to me, he felt sure Loury would one day come around.

My own reasons for refraining were somewhat different. Unlike Wilson, I agreed strongly with parts of Loury’s “arrant nonsense.” I found lots more to laud in books like America in Black and White than he did. But as I wrote in National Review, the reason that “so many blacks experience everything from white slights to white flight as evidence of racial prejudice” is because “from ex-offenders on the streets of Trenton…to graduate students” on Princeton’s campus, they sometimes “actually do experience such things when dealing with whites.”

In defense against the Left’s tendency to racialize everything about American life, American conservatives often acted as if racial prejudice simply did not exist, or at least played no appreciable role in aggravating the problems of black communities. In umbrage at this willful indifference and eager for approval among the smart set, Loury veered too far leftward. But in the midst of it all he was saying something conservatives in the mid-’90s truly needed to hear. Few seemed willing to listen.

***

Even including his “arrant nonsense” period, Loury has batted at least .750 overall on policy-relevant analyses, diagnoses, and prescriptions. For instance, in 1976, based on his dissertation research, he coined the term “social capital” to bring the complex math behind that concept down to earth. He is responsible for explaining the basic principle that “it is easier for people to acquire productive traits when they are socially linked with others who have been successful.”

It is effectively impossible for honest analysts of whatever ideological stripe to discuss racial inequality without discussing Loury’s ideas. He has published many papers that top economists consider to be indispensable. His podcast, The Glenn Show—launched in 2012 right as he was coming back around to more conservative views—offers lucid discussion of myriad issues, from the mundane to the controversial. Still filled even now with self-doubt, he wonders in Late Admissions whether he has “made any lasting contribution to the field of applied economic theory.” He adds that “time will serve as the arbiter.” Yet there is little doubt that time will be kind to his work.

All the same, there were some genuine blunders during his anti-conservative phase. For example, not long after James Q. Wilson died in 2012, Loury set about “demonizing” him in Boston Review—a man who had defended him at considerable cost, “a man I knew to be honorable.” Loury caricatured Wilson’s corpus on crime as being all about tough enforcement, aggressive policing, and harsh policies. As Brandon Welsh and David Farrington documented in a 2013 Journal of Criminal Justice article (“Preventing Crime is Hard Work”), Wilson was the major force both in public and behind the scenes in getting crime prevention research funded and crime prevention policies high on the public agenda. But Loury damned Wilson because he knew that would win him another “chorus of amens” from his left-wing fellow travelers. Wilson would have been surprised by Loury’s attack, but not by his belated yet sincere apology. He never doubted Glenn’s smarts or his heart.

***

Throughout Late Admissions, Loury distinguishes between his “cover story” and his “real story.” For example, when he quit the charismatic black Christian church in Boston that aided his first attempts to break his addictions, his cover story was that he was questioning his faith in Jesus Christ’s divinity. Like Loury’s other cover stories, this one was not all baloney. In public talks, he has said that he came to consider the spiritual convictions that helped free him temporarily from his addictions to be a “benevolent delusion.”

But, of course, Loury was too smart not to know that Christianity of various forms has claimed many among the world’s leading minds, scientific and otherwise. He was too learned not to know that everyone from Saint Augustine to Mother Teresa has struggled to believe. A mentor, the late editor of First Things Father Richard John Neuhaus, told him as much. The real story was that his “infidelity” had “started up again,” and he loved straight-laced church life far less than he loved the “life of infidelity and sexual indulgence.”

But the ultimate “real story” in Late Admissions is that Loury’s life has been a nonstop search for truth. He sought to be true to his South Side Chicago upbringing, and to his “blackness.” He sought abstract truth in economic theories. He sought spiritual clarity first in the church, then in the more secular fervor of eschatological politics. Even when immersing himself in sex and drugs, he was motivated by the craving for a kind of sensual honesty.

The search led him down plenty of blind alleys, plenty of dead ends. But there was always the hunger, deeper even than all his other addictions and insecurities, for real truth—not the passing satisfactions of yet another one-night stand, but the kind of raw sincerity we encounter in this book and in Loury’s best work. In the end, he could never deny the truth when he met it. And when he meets the Maker in whom he no longer believes (God grant that it not be for many years yet), Black Walrus, the boy who grew up to be a truth addict, will be deeply and duly mourned by the many people who love him—and by all people of good will.

John J. DiIulio, Jr. is the Frederic Fox Leadership Professor of Politics, Religion, and Civil Society at the University of Pennsylvania.

Leave a comment