By Lord Buckbeak – Feb 11, 2015

As we know a lot depends (as with all things) on definitions. Just what the phrase ‘image of God’ means is subject to some debate.

I have generally given the answer from the Wizard of Oz movie: to be like God is to have a heart, a brain and a will (or courage), or from the Shema:

Deut 6:4-5 “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might.”

This, the greatest commandment, is stated in scripture variously as:

Luke – Heart, soul, strength and mind

Mark – Heart, soul, mind and strength

Matthew – Heart, soul and mind

Deut – Heart, soul and might

Me – Heart, might, mind and will

So one definition of the image of God is for a creature to have a heart to love God, a mind to know God and a will to obey God. This would obviously apply to angels. Angels are also referred to as ‘sons of God’ as is Adam and so this too would imply they bear the image of God. Also the famous ‘Let us make man in our image’ could be God counseling with the hosts of heaven (not by way of advice but by including them in His decision) and scripture says ‘the sons of God rejoiced’ at the creation (Job 38).

From the website wisdomandfollyblog.com we have the following:

Are angels made in the image of God? Some answer negatively on the basis of the fact that Scripture affirms this of human beings (cf. Gen. 1:26-27) but nowhere explicitly says the same of angels. But to conclude from this fact that angels must not be made in God’s image is a case of the ad ignorantium fallacy (appealing to ignorance). In fact, there are many good reasons to believe that angelic beings are divine image bearers:

- The Essence of Divine Imaging—What does it mean to bear the divine image? Presumably this has to do with certain essential “soulish” capacities that a being has in common with the Deity. Three such characteristics come to mind: (a) cognitive capacity—the ability to use reason, form beliefs, perceive things, etc.; (b) conative capacity—the ability to make choices or act intentionally; and (c) moral capacity—being such that one’s choices are susceptible to ethical evaluation (praise and blame) and having duties or obligations. Do angels have such capacities? According to the biblical accounts, angels clearly have cognitive, conative, and moral capacities just as humans do. It would appear, then, that they bear the image of God.

- “A Little Lower than the Angels”—It is said about Jesus that God “made him a little lower than the angels” (Ps. 8:5 and Heb. 2:7). Presumably this refers to the fact that in sending his Son to Earth in human form he was in this way making him “lower than the angels.” But if humans bear God’s image and angels don’t, then surely humans would not properly be considered “lower” than angels. It seems, then, that angels also must be divine image bearers.

- The Glory of Angels—It is clear from many biblical passages that angels are immensely glorious beings, so much so that even righteous people are tempted to worship them (cf. Rev. 19:10). Moreover, angelic beings such as the archangel Gabriel, are given significant cosmic responsibilities. The notion that such beings do not also bear the image of God seems incongruent with these facts.

- Angelic Impersonations of Humans—In some biblical narratives angels appear in human form (e.g., Gen. 18-19, Gen. 32:22-32, Heb. 13:2, etc.) in order to perform certain tasks. And down through history there have been thousands of reports by Christians of encounters with angels in human guise. The fact that such impersonations occur also seems incongruent with the denial that angels are divine image bearers.

However if there is a different definition of image of God we get a different answer. If the word ‘in’ is translated ‘as’ we have:

‘Let us make man as our image.’ This would make men image bearers more than images of God.

The Lexham Bible Dictionary

The Image as a Physical Attribute. The image of God is often defined as an ability dependent on the human brain, including:

• Intelligence

• Rationality

• Emotions

• Volitional will

• Consciousness

• Sentience

• The ability to communicate.

Many of these options are coherent, but defining the image of God in any of these ways fails exegetically and creates a problem for beginning of life and end of life ethics:

• All are not equally present among all human beings.

• All are not present in all human beings at all times.

• Some are not unique to human beings.

For example, the fertilized human embryo does not possess these abilities or attributes. To an embryo, they are potential attributes. If the image of God is said to be any of these things, the human only potentially bears the divine image until those attributes are possessed. This means that one must either deny the human personhood of the embryo or produce a more coherent alternative for defining the image of God. Even after birth, these options would mean that a severely retarded or brain-damaged child does not bear the divine image. Such definitions, if held consistently, would result in the loss of the image for some human beings.

Scientific and psychological research question whether some of these attributes are unique to humans. In regard to intelligence, the field of animal cognition has demonstrated that many animals have intelligence that cannot be assigned merely to instinct (Griffin, Animal Thinking; Pearce, Animal Learning and Cognition). For example, the ability to remember instructions or act contrary to instinct constitutes intelligence. Several species of mammals and birds score higher on simple intelligence tests than human infants or toddlers. Animals have been shown to grieve as well, so human emotion is not unique. Animals also show the ability to communicate (Savage-Rumbaugh, “Language Learning in Two Species of Apes”).

Scripture gives no indication that the divine image is bestowed incrementally or intermittently, and demands that the image must be unique to humans with respect to creation.

The Image of God as the Immaterial Nature of Humans. Humanity’s inner or “spiritual” nature may offer a better strategy for defining the image of God.

Spiritual Abilities. “Spiritual abilities” are “God-directed” abilities or spiritual inclinations of the inner life. Examples include:

• The belief in God

• A desire to know God

• Prayer

• Knowing right from wrong

These abilities require cognition. As with the physical abilities that require brain function, spiritual abilities or desires are not possessed equally by all humans. Furthermore, some animals may possess moral awareness (Putz, “Moral Apes”; Griffin, Animal Minds).

The faculty of knowing right from wrong is specifically denied as being part of the image of God. Scripture is clear that this sort of moral awareness only came about after humanity’s creation in God’s image, not in association with it. As Bray points out: “[C]onferred moral awareness is directly contradicted by the narrative in Genesis itself. It is extraordinary that this was never recognized, yet it is plain for all to see that Adam, though he was created in the image of God, was not allowed to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. When he did so, God said ‘Behold, the man has become like one of us,’ implying that in this particular at least, there had been an important dissimilarity between Himself and His human creature” (Bray, “The Significance of God’s Image in Man,” 207).

The Meaning of the Image of God

A more coherent understanding can be found by appeal to Hebrew syntax with respect to the prepositional phrase בְּצֶלֶם (betselem). The preposition (ב, b) should be understood as what Hebrew grammarians variously refer to as:

• The “beth of essence (beth essentiae) or equivalence” (Joüon and Muraoka, A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew, 2:487).

• The “beth of identity” (Waltke and O’Connor, An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax, 198).

• The “beth of predication” (Gordon, “ ‘In’ of Predication or Equivalence,” 612–13).

The preposition “in” should be understood as meaning “as” or “in the capacity of.” Humanity was created “as” the image of God. The concept can be conveyed if we think of “image” as a verb: Humans are created as God’s imagers—they function in the capacity of God’s representatives. The image of God is not a quality within human beings; it is what humans are. Clines summarizes: “What makes man the image of God is not that corporeal man stands as an analogy of a corporeal God; for the image does not primarily mean similarity, but the representation of the one who is imaged in a place where he is not.… According to Gen 1:26ff, man is set on earth in order to be the representative there of the absent God who is nevertheless present by His image (Clines, “The Image of God in Man,” 87)”

Every human, regardless of the stage of development, is an imager of God. There is no incremental or partial of the image via some ability, physical or spiritual. No member of the animal kingdom, regardless of any cognitive ability it might have, is an imager of God. The same goes for any intelligent life form, artificial or the hypothetical extraterrestrial.

This understanding lends clarity to the Old Testament passages. Being created as God’s imagers means we are His representatives on earth—the only qualification for this is that we are human. This is why the creation of humankind as God’s image in Gen 1:26–27 is immediately followed by the so-called dominion mandate of Gen 1:28. Humanity is tasked with stewarding God’s creation as though God were physically present to undertake the duty himself. Genesis 9:6’s requirement of capital punishment for murder is because the intentional killing of an innocent human was tantamount to killing God in effigy. Clines argument with respect to Gen 5:1–3 is also brought into sharper focus: “Seth is not Adam’s image, but only like Adam’s shape” (Clines, “The Image of God in Man,” 78n117). Seth resembled Adam, but he was not Adam’s representative on earth. The prepositional changes in Gen 5 serve to distinguish the point of Gen 1:26–27 from Gen 5:1–3.

This view means that all human endeavor and enterprise has spiritual meaning—work is a spiritual exercise. Vocation is worship, no matter how mundane. Any task performed to steward creation, to harness its power for God’s glory and the benefit of fellow imagers, and to foster in the harmonious productivity of fellow imagers, is imaging God. This application of the image has been referred to as the “cultural mandate” or the vocational view of the imago Dei (Sands, “The Imago Dei as a Vocation”).

The Plural Language Associated with the Image of God

Problematic Interpretations of the Plurality. The plurality in the expression “let us create humankind in our image” may point to plurality within God. Christians see the Trinity in this language. However, an ancient Israelite or Jew never would have presumed this (Wenham, Genesis 1–15, 27–28; Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, 133–34). This option reads the New Testament back into the Old—the language does not specify (or limit) the plurality to three persons. The Old Testament uses the language of divine plurality in contexts that, were the Trinity to be imported into the passage, would result in its members being corrupt and wicked (Psa 82; Heiser, “Monotheism, Polytheism, Monolatry, or Henotheism?”).

Plurality may be an example of the “plural of majesty,” a grammatical use of the plural to point to “a fullness of attributes and powers” (Wenham, Genesis 1–15, 28). However, the plural of majesty is not used with pronouns or verbal forms, the latter of which is present in Gen 1:26 and 11:7.

In reference to Isaiah 6:8, the plural language in Gen 1:26 may be a self-deliberation or self-encouragement. This perspective is akin to the “editorial we.” The plurality describes how people deliberate with themselves. However, it is difficult to see how this view can work with the meaning of the image as God’s representative. It is also difficult to cohere this view with Psa 8, in which humanity is said to have been created a little lower than elohim (Psa 8:5). That the word elohim is to be taken as a plural is evident from its citation in Heb 2:7, where the writer quotes the passage from the Septuagint, which renders elohim as “angels.”

Some look to humanity as the referent of the plurality. Bray writes, “A more awkward question is raised by the use of the plural in Gen 1:26, implying as it does that man, as the image of God, somehow reflects a plurality in God” (Bray, “The Significance of God’s Image in Man,” 197).

An Announcement to the Heavenly Host. In Genesis 1:26, God, the lone speaker, is probably announcing His intention to create humankind to the members of His heavenly host (Psa 82; 89:5–8). Wenham writes, “From Philo onward, Jewish commentators have generally held that the plural is used because God is addressing his heavenly court” (Wenham, Genesis 1–15, 27).

As humans, we use this sort of language with regularity. A mother could announce to her family, “let’s make dinner”—and then proceed to do so herself, for their benefit, without their involvement in the event. This is more coherent than a mere rhetorical self-reference since it involves the audience, though without necessarily requiring their active participation. This is also the most coherent explanation for the other plurality language we have touched upon (Gen 11:7; Isa 6:8). God among his heavenly host is a familiar biblical description (Deut 33:1–2; Psa 68:17; 1 Kgs 22:19–23).

Bray notes: “More probable is the idea that God is here speaking to the heavenly hosts, though this raises such questions as whether angels are also created in the image of God, whether angels took part in the work of man’s creation” (Bray, “The Significance of God’s Image in Man,” 198). Clines asserts that this view “would imply that man was made in the image of the elohim as well as of God Himself (‘in our image’); it would mean that the elohim shared in the creation of man (‘let us make’)” (Clines, “The Image of God in Man,” 66).

The text is clear that the angels did not participate in the creation of humankind. The singular suffix (“so God created humankind in His image”) makes that point as well. There is no contradiction if “let us create” is taken as an announcement of the single Creator to a group.

Angelic beings are also divine imagers—representatives of their Creator. While humans image God on earth, angelic beings image God in the spiritual world. They do God’s bidding in their own sphere of influence. The Old Testament and New Testament describe angelic beings with administrative terminology, such as:

• “Prince” (Dan 10:13, 20–21)

• “Thrones” (Col 1:16)

• “Rulers” (Eph 3:10)

• “Authorities” (1 Pet 3:22; Col 1:16)

First Kings 22:19–23 illustrates the heavenly bureaucracy at work. Angelic beings were created before the earth, and therefore before humans (Job 38:7–8). The notion that God decided to make humans to represent Him and His will on earth mirrors what God had already done in the spiritual world. God announces that, as things are in the heavenly realm, so they will be on earth. Humanity is lesser than angelic beings. However, humans are not their representatives, but are destined to rule over angels and to inherit the nations ruled by some of the sons of God (1 Cor 6:3; Rev 2:26).

The Image of God in the New Testament

The functional view of the image described argues that the phrase means humans are created as God’s image. Taking that understanding to the New Testament’s image of God language brings the meaning and importance of the image doctrine in New Testament theology into clear focus.

Paul argues that believers are destined to be conformed to the image of Christ (Rom 8:29). We are to live as God would, to represent him and his character. Paul elsewhere refers to Jesus as the image of God (2 Cor 4:4). The writer of Hebrews uses the same verbiage, calling Jesus “the express image of God” (Heb 1:3). As humans gave visible form to God, so Jesus is the image of the invisible God (Col 1:15). Jesus was truly incarnate, becoming human to atone for humankind, but also an example for humankind (Phil 2:6–10; 1 Pet 2:21).

These New Testament passages convey that Jesus was the imager of God. As Jesus imaged God, we must image Jesus. In so doing, we fulfill the rationale for our creation. This process is gradual: “And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another. For this comes from the Lord who is the Spirit” (2 Cor 3:18). Paul also links our resurrection to Jesus as the image of God in 1 Cor 15:49.

Imago Dei

by Mark Ross

The opening chapter of our Bible is a thrilling story of creation and formation, laying the foundation for all that follows. We are told that “in the beginning” our home in the universe, the earth, was formless and void, covered in water and shrouded in darkness, while the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters (v. 2). As the days of creation unfolded, God gave form to the earth and filled it. He separated the day from the night, the waters above from the waters below, and the dry land from the waters below. God filled these realms by putting lights in the sky to separate the day from the night, creating living creatures to swim in the waters below and birds to fly in the sky above, and causing the earth to bring forth living creatures on the dry land. Finally, as the culminating act, God created another type of living being, man.

The focus of the narrative clearly falls on this creature. Not only was this the final act of creation, but fully one-fourth of the story is centered on it. Something very special and quite important is before us.

The chapter divides the totality of beings into two basic categories: the Creator and the created. God stands alone as the uncreated Lord of all, the maker of the heavens and the earth. Everything else is created and, thus, finite, temporal, dependent, and changeable. Some are living creatures (the plants and the animals). Some have the breath of life in them (v. 30). Among this group is man. Like other members of the group, man is made both male and female, and called to be fruitful, to multiply, and to fill the earth (vv. 22, 28). Other similarities could be noticed (hair on the skin, females give birth to their young and suckle them, and so on). But for all the similarities that may be noted, there is something about man that makes him quite distinct from all the other creatures.

Living things are first mentioned with the vegetation that God causes to sprout on the dry land (v. 11). Then come the creatures that live in the seas and birds that fly in the air (v. 20), livestock, creeping things, and beasts of the earth (v. 24). They are all made according to their kinds. This phrase occurs ten times and leaves a bold imprint on the narrative. It indicates that while there is great diversity among all the living creatures, there are groupings among them that share common features, forming as it were “families” of things, as in the modern distinction between genus and species. But the main purpose of the phrase is not so much to introduce us to the scientific work of taxonomy; rather, it is to provide the background necessary for contrasting human beings with all the other living creatures.

When God makes man, He breaks the pattern that He has set by creating living things according to their kinds. The tenfold mention of this pattern causes us to expect it with each new living creature to appear, but something quite different happens when man is made; he is not made “according to [his] kind.” Neither is man created according to any other kind among the living creatures. Man does not, therefore, belong to their kinds, whatever similarities there may be between him and the other creatures. To put it in modern scientific language, he is not a particular species within a given genus of living creatures. Man is unlike any of the other living creatures (v. 26). Surprising as it is, man is made according to God’s “kind,” made in the image of God (imago Dei). Man, like God, is a personal being. God Himself, as the Bible later reveals, is three persons all sharing one divine essence. Human persons are created beings, and in that regard (as in others) they are similar to and share characteristics with other created beings. But what is most important about human persons is their likeness to God. This likeness is so very special that it sets them apart from all the other creatures God made. Man is not made according to their kinds; he is made according to God’s “kind.” In other words, man is made as the image and likeness of God.

Bearing the imago Dei, the human persons are given a measure of sovereignty over all the earth, with dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, the livestock, and every creeping thing (v. 28). They are also charged to subdue the earth (v. 28). The language suggests a ruling, even conquering position, as Psalm 8 makes plain (see vv. 5–8). All things are placed under man’s feet, but tyranny and exploitation are not in view. Genesis 2:4–25 shows that man is to follow the example of God in his stewardship of the earth. God plants a garden in Eden, and He puts the man there to work it and keep it (2:8, 15). What God initiates, man is to sustain and cultivate. God names the light day and the darkness night; He calls the expanse heaven and the waters seas (1:5, 8, 10). Now God commissions man to name all of the living creatures that He has made (2:19).

Though not using the vocabulary of image and likeness, Genesis 2 has its own way of underscoring the uniqueness of human persons among all the living creatures. When God formed the man from the dust and placed him in the garden, He declared that it was not good for the man to be alone. So, God determined to make a helper fit for him (2:18). Following this solemn declaration, God presented all the animals that He had made to the man, in order that the man might name them. Why this parade of animals before the man? Why did God not immediately create the woman? What looks like an interruption in the story is actually driving home the motivation for the story: “But for Adam there was not found a helper fit for him” (v. 20). The point is that human beings do not really belong to the animals, whatever characteristics they might share with them. There was not found among all the animals a helper fit for Adam, a created being of the same kind as he, with whom he could fulfill his calling from God. Thus, God made a woman, who was “bone of [his] bones and flesh of [his] flesh” (v. 23). Like Adam, she was made in the image and likeness of God (1:28). Together they were to labor in fulfilling the work of God to be fruitful, to multiply, and to fill the earth and subdue it. God made the first male and female, but all other humans would come into existence through them. What God did, the man and woman now were to continue, having been made in the image and likeness of God.

Tragically, the man and the woman turned away from God and fell into sin, seeking to become yet more like God (3:5); to choose for themselves what is good and evil. The image of God was defaced. Though made upright, they sought out many schemes (Eccl. 7:29). Their descendants would likewise bear this defaced image (Rom. 5:12–21).

Yet the image of God was not entirely lost, and what remains is still sufficient to sustain the sanctity of human life that is grounded in the imago Dei. Genesis 9:6 shows that taking innocent human life is an attack on the image of God, so it must be punished by death. Man as the image of God is to be a giver of life, not a taker of innocent life. When we become murderers, we contradict our purpose in life and forfeit the divine protection that ordinarily covers us. So special is our life to God that even a beast is put to death if it takes the life of a human being (Gen. 9:5, Ex. 21:28–32).

Further, as we are to respect God and bless Him by our words, so we must never curse those made in the likeness of God (James 3:9). The whole of human ethics is grounded in the imago Dei. Husbands must love their wives as Christ loved the church (Eph. 5:25–27). Fathers must discipline and instruct their children as the Lord does His children (6:4). The comforting love of a mother is the image and likeness of the comforting love of God (Isa. 66:13). Earthly masters should reflect the justice and fairness found in the heavenly Master (Eph. 6:9; Col. 4:1). Though sin has greatly defaced God’s image in us, by God’s grace in Christ that image is renewed (Eph. 4:24; Col. 3:10). Living by that grace, people see our good works and give glory to our Father who is in heaven (Matt. 5:16). When our restoration is complete, we shall forever live in the presence of God, clothed with His glory (Rev. 21–22), having truly become His “kind” of people. Thanks be to God.

First published in Tabletalk Magazine, an outreach of Ligonier. For permissions, view our Copyright Policy.

The following is a very well reasoned answer defining the image of God as ‘doing what God does’.

From the website www.preachitteachit.org we have:

Man and Angels: Are Both in God’s Image?

04/08/11

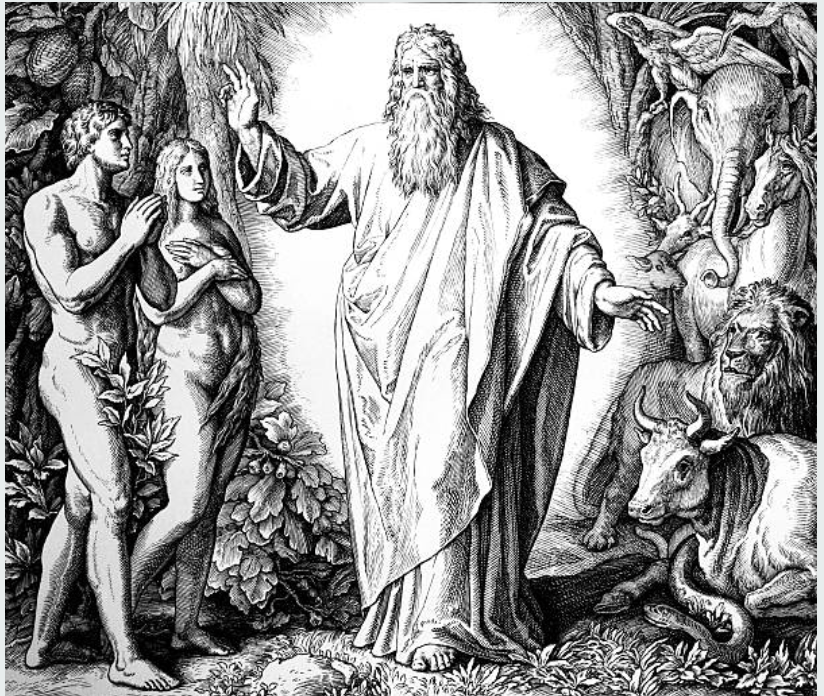

Have you ever read Genesis 1:26 and wondered what in the world God was talking about when he decided to make man in God’s image? The passage reads, “Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness; and let them rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over the cattle and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.”

Many people have speculated about the image of God, thinking that it refers to man’s intellectual capacity, or his ability to make moral judgments. Many have wondered if angels are made in God’s image since they would seem to be above us in the current created order (Psalm 8:5; Hebrews 2:7). Angels seem to be able to have intellectual capacity and make moral judgments. So how can man, being lower than the angels be created in God’s image and the angels being higher than man not be in God’s image? These are interesting speculations. However, the scripture does not seem to refer to such characteristics as being the reason why man is categorized as being in God’s image.

I believe that the answer to the issue of what it means to be in God’s image is easily found in the scripture. I believe the answer is found right in the text of Genesis 1 for all to see. In fact, from what we know about the angels I think that in Genesis 1 we have the answer as to why man is in God’s image and the angels are not.

This can be a complex issue and I don’t want to treat it in a cavalier manner. Yet space is limited so I encourage you to study and think on this issue after you read what I have to say.

The answer to our inquiry about God’s image is found by combining what we know about the Adamic covenant with God’s creative acts. Let’s first outline the command that God gives concerning Adam. God says in Genesis 1:26 that man is to rule over the earth. He repeats this idea in verses 27 and 28 when he said to Adam, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it; and rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over every living thing that moves on the earth.”

These are very important commands, and they form the first part of the covenant God made with Adam. That covenant is still in place today for you and I. It is God’s covenant with man—regardless of whether man is a believer or not. What did God command man to do?

• Be Fruitful

• Multiply

• Fill the earth

• Subdue

• Rule

Have you ever wondered why God issued these five commands to man? He did so because in the preceding verse (26) he declared man to be made in his image. These two ideas are inseparably linked.

What is an image? An image is a representation of something else. It bears the characteristics of, or performs a function, which is similar to the original thing it represents. Since the Bible is an ancient book written to an Ancient Near East (ANE) culture, we should look to the popular images of that day to help us interpret what an image’s purpose was during that time. Probably the best example is that popular god images of the ANE we’re used to establish and extend the rule of the supposed god the image represented. In fact, even in the New Testament era with the empire of Rome, images of the ruling Caesar were spread throughout the kingdom as a sign that Roman authority extended to other lands, signified by the presence of these false images.

This is what the concept of an image represents in Genesis. By making man in God’s image, God’s intent is to demonstrate his rule and authority over his territory. Man is, essentially, his regent. But there is much more to the concept of man as God’s image than simple rulership.

When God declares that we are in his likeness he is essentially saying that we are to be like him. But how are we supposed to be like him? Look at the list:

• Be Fruitful

• Multiply

• Fill the earth

• Subdue

• Rule

If we are to be like him, and if these things are the visible sign that we are like God then we must ask the question, when did God do these things? The answer is found in God’s creative acts.

When was God fruitful? When he created all things, particularly, man.

When did God multiply? He did not multiply himself rather he multiplied by creating man who was designed to be like God.

When did God fill the earth? When he created all life in the seas and on the earth.

When did he subdue? When he brought the undefined mass of the earth under his control to form the earth’s habitation.

When did he rule? When he issued his first command to man to do these very same things that God himself did.

But what about the angels? If the angels are higher than man aren’t they also in God’s image?

If we define God’s image according to what we’ve discovered in scripture then it would seem that angels, though powerful and intelligent, are not made in God’s image. Why?

Are angels fruitful and multiply? We have no record in the scripture that angels function in this way. Angels, it would seem, don’t have children or create disciples. But man is specifically equipped and commanded to do these things as also God did.

Do angels fill the earth in the sense of spreading themselves over the earth to extend their rule? No. Earth is the realm that God has given in trust to man. Angels serve man’s needs on earth according to God’s instructions, but they do not extend a rule they have been given as man has been given.

Do angels subdue, that is, create things and bring things under their control? We might note that angels are spiritual warriors to fight against the demonic to bring things under God’s influence. But we have no record that angels do this in a creative fashion as man does.

What about rule? Do angels rule? Certainly there are angels that have authority. But do they rule in the same way that man is commanded to rule in Genesis? We have no indication that this is so.

In one sense we are making an argument regarding angels from what the Bible does not say. That can be a bit tricky. Yet what the Bible does reveal about angels would seem to support these conclusions.

So, what is God’s image? Let’s put it this way: God was essentially telling Adam, “Adam, do what I do.” It’s just that simple. Man is made to experience life in a similar, though limited way, as God does. Man is to be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue and rule because that is what God did when he created all things. By doing these things God was acting out of his character and he has enabled us to do the same thing. We are his image therefore, we must do what God does.

This realization of the high station that God has given us should encourage us. The worth you and I have before God is higher than any other created thing. We are designed to think what he thinks, feel what he feels, and do what he does. What higher place for a person can there be but that? You and I have inestimable value before God because we were created to be like him. It’s that simple.

In the Mosaic Law God commanded that Israel was not to make any images of God or false gods. Why? Because the image of God had already been established in man. And it was established a second time in Christ, whose function as God’s image, unlike Adam, was never corrupted. We are therefore unique in all of creation.

Leave a comment