Sculptor’s Model Fleshes Out Ancient Face

L.A. TIMES ARCHIVES – FEB. 15, 1998 12 AM PT –

FROM ASSOCIATED PRESS – KENNEWICK, Wash. —

My cmnt: You will see in the following articles the alarm it caused among the Lib-Left that the Kennewick Man might be European and therefore older than the so-called Native American Indians. Let’s first get real here. The democrat-Lib-Left establishment doesn’t give a damn about facts, truth or even reality. The very idea that “white” Europeans just might be the first Native Americans sent seismic shock waves thru the dominant, mainstream cultural establishment. If this were proved to be true the destruction of one of the Left’s primary talking points would be monumental.

My cmnt: These articles provide a lot of interesting story lines. We must remember that in the field of human anthropology there is so much at stake that the scientists themselves cannot be trusted to reveal the truth about their actual findings. The Darwinist scenario requires certain outcomes to be produced whether or not the data supports it. When the Church of Big Government with its democrat priesthood is funding the research with our tax dollars they are expecting, as with climate research, a certain, favorable (politically) conclusion to be reached – data be damned.

My cmnt: As it turned out the Kennewick Man is neither European nor Native American but rather a sea-faring man from the Ainu people of Japan. By Lib-Left logic (an oxymoron) it now turns out that the Japanese during WWII were simply trying to reclaim America and specifically Hawaii for themselves as the original inhabitants, from whom the American Indians stole their land.

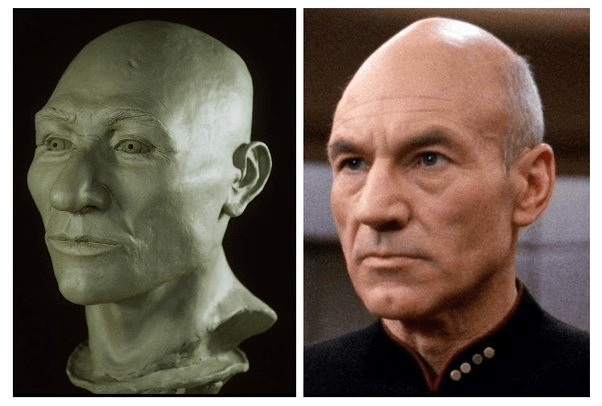

An anthropologist made a clay model of the head of a 9,200-year-old man, only to discover it bears a strong resemblance to someone with links to the distant future.

Anthropologist Jim Chatters and sculptor Tom McClelland produced a clay model of what the so-called Kennewick Man likely looked like when he roamed the Columbia River basin more than 90 centuries ago.

He has a narrow chin, prominent cheekbones, a long face, a prominent nose, a size 15 neck and a forehead that slopes to its apex far to the back of his head.

Without a wig, it resembles Patrick Stewart, the actor who played Capt. Jean-Luc Picard in television’s “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” Chatters said.

The sculpture looks somewhat like the bust of a Roman dictator, but “you could lose him in the streets of most major cities,” Chatters said.

“He’s really kind of an Everyman,” McClelland said.

Kennewick Man’s bones were found in July 1996 in a park along the Columbia River in south-central Washington.

Chatters is one of only a few people to have examined the bones before they were locked away in a dispute between scientists and American Indians.

Eight scientists are suing the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for the right to study the bones, which they believe could reveal much about how people first came to North America. Early study of the bones found indications they had Caucasian features.

Representatives of mid-Columbia Indian tribes contend the bones were uncovered at an ancient burial ground and should be returned under a 1990 federal graves protection law.

Chatters said he thought about reconstructing the skull’s features ever since the bones were found.

“We’re translating the language the bones have to a language that anyone can understand,” Chatters said of the three-dimensional creation.

McClelland, a freelance sculptor and art teacher at Columbia Basin College, said the work helps bring Kennewick Man beyond the politics surrounding his discovery in the river mud.

“We’re creating a tangible object that represents the humanity of the individual,” he said. “It’s a merging of science and art.”

The sculptors said the sculpturing involves some interpretation– especially in the later stages of creating lines in the skin and forming the lips and eyes.

“We’re not trying to make him look like anybody in particular,” McClelland said. “What we wanted to see was what the bones were trying to tell us.”

The reconstruction doesn’t resemble modern Northwest Indians, but has some characteristics of Eastern tribes such as the Iroquois, McClelland said.

Chatters and McClelland used a mold of Kennewick Man’s skeleton that Chatters took before the bones were placed in a vault under court order. To gauge the tissue depth on Kennewick Man’s face, they used the average depth found on Asian and American males at 21 spots around the face.

By using that average, they tried to reduce a bias toward European features, Chatters said.

“Most people just use the European [measurements], but I didn’t think that was appropriate in this case because of the issues that have been brought up,” he said.

There are no plans to display the sculpture.

The sculpture looks like a man about 30 years old, and the sculptors plan to age it another 15 or 20 years to make it look as he might have at death.

“There is still quite a bit of aging to be done,” McClelland said. “Because he lived primarily outdoors, there would have been a lot of weathering, a lot of creasing, a lot of aging.”

New DNA Results Show Kennewick Man Was Native American

By Carl Zimmer – June 18, 2015 – The New York Times

In July 1996, two college students were wading in the shallows of the Columbia River near the town of Kennewick, Wash., when they stumbled across a human skull.

At first the police treated the case as a possible murder. But once a nearly complete skeleton emerged from the riverbed and was examined, it became clear that the bones were extremely old — 8,500 years old, it would later turn out.

The skeleton, which came to be known as Kennewick Man or the Ancient One, is one of the oldest and perhaps the most important — and controversial — ever found in North America. Native American tribes said that the bones were the remains of an ancestor and moved to reclaim them in order to provide a ritual burial.

But a group of scientists filed a lawsuit to stop them, arguing that Kennewick Man could not be linked to living Native Americans. Adding to the controversy was the claim from some scientists that Kennewick Man’s skull had unusual “Caucasoid” features. Speculation flew that Kennewick Man was European.

A California pagan group went so far as to file a lawsuit seeking to bury the skeleton in a pre-Christian Norse ceremony.

On Thursday, Danish scientists published an analysis of DNA obtained from the skeleton. Kennewick Man’s genome clearly does not belong to a European, the scientists said.

“It’s very clear that Kennewick Man is most closely related to contemporary Native Americans,” said Eske Willerslev, a geneticist at the University of Copenhagen and lead author of the study, which was published in the journal Nature. “In my view, it’s bone-solid.”

Kennewick Man’s genome also sheds new light on how people first spread throughout the New World, experts said. There was no mysterious intrusion of Europeans thousands of years ago. Instead, several waves spread across the New World, with distinct branches reaching South America, Northern North America, and the Arctic.

“It’s probably a lot more complicated than we had initially envisioned,” said Jennifer A. Raff, a research fellow at the University of Texas, who was not involved in the study.

But the new study has not extinguished the debate over what to do with Kennewick Man.

Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues found that the Colville, one of the tribes that claims Kennewick Man as their own, is closely related to him. But the researchers acknowledge that they can’t say whether he is in fact an ancestor of the tribe.

Nonetheless, James Boyd, the chairman of the governing board of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, said that his tribe and four others still hope to rebury Kennewick Man and that the new study should help in their efforts.

“We’re enjoying this moment,” said Mr. Boyd. “The findings were what we thought all along.”

The scientific study of Kennewick Man began in 2005, after eight years of litigation seeking to prevent repatriation of Kennewick Man to the Native American tribes. A group of scientists led by Douglas W. Owsley, division head of physical anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution, gained permission to study the bones.

Last year, they published a 670-page book laying out their findings.

Kennewick Man stood about 5 foot 7 inches, they reported, and died at about the age of 40. He was probably a right-handed spear-thrower, judging from the oversized bones in his right arm and leg.

Based on the chemical composition of his skeleton, the scientists concluded that he originally lived on a distant coast. However he got to Kennewick, the Ancient One had been embraced by the community there: his body was buried carefully after his death, the scientists noted.

The archaeologist James Chatters initially described the skull as Caucasian, and produced a reconstruction of his face famously suggesting that Kennewick Man looked a bit like the actor Patrick Stewart. But eventually Dr. Chatters decided against the European hypothesis, swayed by the discovery of other old Native American skulls with unusual shapes.

Other scientists, including Dr. Owsley and his colleagues, suggested the skull resembled those of the Moriori people, who live on the Chatham Islands 420 miles southeast of New Zealand, or the Ainu, a group of people who live in northern Japan. They speculated that the ancestors of the Ainu might have paddled canoes to the New World.

In 2013, one of the scientists examining the skeleton, Thomas W. Stafford of the University of Aarhus in Denmark, provided Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues with part of a hand bone. Dr. Willerslev and other researchers have developed powerful methods for gathering ancient DNA.

Once they had assembled the DNA into its original sequence, the scientists compared it with genomes from a number of individuals selected from around the world. They also examined genomes from living New World people, as well as the genome Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues found in a 12,600-year-old skeleton in Montana known as the Anzick child.

This analysis clearly established that Kennewick Man’s DNA is Native American. But the result is at odds with the shape of his skull, which seemed to be very different from living Native Americans.

To explore that paradox, Dr. Willerslev collaborated with Christoph P. E. Zollikofer and Marcia S. Ponce de Leon, experts on skull shapes at the University of Zurich.

In the new research, Dr. Zollikofer and Dr. Ponce de Leon demonstrated that living Native Americans include a wide range of head shapes, and Kennewick Man doesn’t lie outside that range.

Still, it would take many skulls of Kennewick Man’s contemporaries to figure out if they were distinct from living Native Americans. A single skull isn’t enough.

“If I take my own skull and print it out with a 3-D printer, many people would see a Neanderthal,” said Dr. Zollikofer.

After determining that Kennewick Man was a Native American, Dr. Willerslev approached the five tribes that had fought in court to repatriate the skeleton. He asked if they would be interested in joining the study.

“We were hesitant,” said Mr. Boyd, of the Colville Tribes. “Science hasn’t been good to us.” Eventually, the Colville agreed to join the study; the other four tribes did not.

The Colville Tribes and the scientists worked out an arrangement that suited them all. Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues sent equipment for collecting saliva to the reservation. Colville tribe members gathered samples and sent them back.

In exchange for permission to sequence the DNA, Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues agreed that they would share the data with other scientists only for confirmation of the findings in the Nature study.

Dr. Willerslev also invited representatives of the five tribes to Copenhagen, where they observed the research in his lab. They donned body suits to enter a clean room in the lab in order to perform a ceremony in honor of the Ancient One.

Kim M. TallBear, a cultural anthropologist at the University of Texas, praised the way the scientists worked with the Native Americans. “There’s progress there, and I’m happy about that,” she said.

When Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues looked at the Colville DNA, they found that it was the closest match to Kennewick Man among all the samples from Native Americans in the study.

But other scientists stressed that the new study didn’t have enough data to establish a tight link between Kennewick Man and any of the tribes in the region where he was found.

Unlike in Canada or Latin America, scientists in the United States do not have many genomes of Native Americans. Dr. TallBear saw this gap as a legacy of the distrust between Native Americans and scientists.

In addition to the conflict over Kennewick Man, the Havasupai Indians of Arizona won a court case in 2010 to take back blood samples that they argued were being used for genetic tests to which they didn’t consent. Some scientists may be reluctant to get into a similar conflict.

“People are scared post-Havasupai,” Dr. TallBear said.

As a result, said Dr. Raff, scientists can’t rule out the possibility that Kennewick Man is an ancestor of another tribe, or that he is the ancestor of many Native Americans. “It’s impossible to say without additional data from other tribes,” she said.

To Dr. Raff and other researchers, the most significant result of the new study is how Kennewick Man is related to other people of the New World.

The new study points to two major branches of Native Americans. One branch, to which Kennewick Man and the Colville belong, spread out across the northern stretch of the New World, giving rise to tribes such as the Ojibwe and Athabaskan.

The Anzick child, on the other hand, appears to belong to a separate branch of Native Americans who spread down into Central and South America. Given the ages of the Kennewick Man and the Anzick Child, the split between these branches must have been early in the peopling of the New World — perhaps even before their ancestors spread east from Asia.

About 4,000 years ago, two more waves of people spread across the Arctic. One lineage, known as the Paleo-Eskimos disappeared several centuries ago, while the other gave rise to today’s Inuit peoples.

The DNA of the Colville tribe contains Asian-like pieces of DNA not found in Kennewick Man. They may have gained that genetic material by having children with the Arctic peoples.

Testing these possibilities will require more Native American DNA, and a better understanding of Native American culture, said Dr. Raff. New programs, such as the Summer Internship for Native Americans in Genomics at the University of Illinois, are giving Native Americans training that they can use to study their own history.

“They’ll have valuable insights to bring into this work themselves,” said Dr. Raff. “It really only strengthens the science to learn from Native Americans about their own history.”

“It doesn’t have to go the way Kennewick Man went at all,” said Dr. TallBear.

A correction was made on – June 18, 2015 – An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of a 12,600-year-old skeleton discovered in Montana. It is known as the Anzick child, not the Anzik child.

The Kennewick Man Finally Freed to Share His Secrets

He’s the most important human skeleton ever found in North America—and here, for the first time, is his story

Douglas Preston September 2014 – The Smithsonian magazine

In the summer of 1996, two college students in Kennewick, Washington, stumbled on a human skull while wading in the shallows along the Columbia River. They called the police. The police brought in the Benton County coroner, Floyd Johnson, who was puzzled by the skull, and he in turn contacted James Chatters, a local archaeologist. Chatters and the coroner returned to the site and, in the dying light of evening, plucked almost an entire skeleton from the mud and sand. They carried the bones back to Chatters’ lab and spread them out on a table.

The skull, while clearly old, did not look Native American. At first glance, Chatters thought it might belong to an early pioneer or trapper. But the teeth were cavity-free (signaling a diet low in sugar and starch) and worn down to the roots—a combination characteristic of prehistoric teeth. Chatters then noted something embedded in the hipbone. It proved to be a stone spearpoint, which seemed to clinch that the remains were prehistoric. He sent a bone sample off for carbon dating. The results: It was more than 9,000 years old.

Thus began the saga of Kennewick Man, one of the oldest skeletons ever found in the Americas and an object of deep fascination from the moment it was discovered. It is among the most contested set of remains on the continents as well. Now, though, after two decades, the dappled, pale brown bones are at last about to come into sharp focus, thanks to a long-awaited, monumental scientific publication next month co-edited by the physical anthropologist Douglas Owsley, of the Smithsonian Institution. No fewer than 48 authors and another 17 researchers, photographers and editors contributed to the 680-page Kennewick Man: The Scientific Investigation of an Ancient American Skeleton (Texas A&M University Press), the most complete analysis of a Paleo-American skeleton ever done.

The storm of controversy erupted when the Army Corps of Engineers, which managed the land where the bones had been found, learned of the radiocarbon date. The corps immediately claimed authority—officials there would make all decisions related to handling and access—and demanded that all scientific study cease. Floyd Johnson protested, saying that as county coroner he believed he had legal jurisdiction. The dispute escalated, and the bones were sealed in an evidence locker at the sheriff’s office pending a resolution.

“At that point,” Chatters recalled to me in a recent interview, “I knew trouble was coming.” It was then that he called Owsley, a curator at the National Museum of Natural History and a legend in the community of physical anthropologists. He has examined well over 10,000 sets of human remains during his long career. He had helped identify human remains for the CIA, the FBI, the State Department and various police departments, and he had worked on mass graves in Croatia and elsewhere. He helped reassemble and identify the dismembered and burned bodies from the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas. Later, he did the same with the Pentagon victims of the 9/11 terrorist attack. Owsley is also a specialist in ancient American remains.

“You can count on your fingers the number of ancient, well-preserved skeletons there are” in North America, he told me, remembering his excitement at first hearing from Chatters. Owsley and Dennis Stanford, at that time chairman of the Smithsonian’s anthropology department, decided to pull together a team to study the bones. But corps attorneys showed that federal law did, in fact, give them jurisdiction over the remains. So the corps seized the bones and locked them up at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, often called Battelle for the organization that operates the lab.

At the same time, a coalition of Columbia River Basin Indian tribes and bands claimed the skeleton under a 1990 law known as the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA. The tribes demanded the bones for reburial. “Scientists have dug up and studied Native Americans for decades,” a spokesman for the Umatilla tribe, Armand Minthorn, wrote in 1996. “We view this practice as desecration of the body and a violation of our most deeply-held religious beliefs.” The remains, the tribe said, were those of a direct tribal ancestor. “From our oral histories, we know that our people have been part of this land since the beginning of time. We do not believe that our people migrated here from another continent, as the scientists do.” The coalition announced that as soon as the corps turned the skeleton over to them, they would bury it in a secret location where it would never be available to science. The corps made it clear that, after a monthlong public comment period, the tribal coalition would receive the bones.

The tribes had good reason to be sensitive. The early history of museum collecting of Native American remains is replete with horror stories. In the 19th century, anthropologists and collectors looted fresh Native American graves and burial platforms, dug up corpses and even decapitated dead Indians lying on the field of battle and shipped the heads to Washington for study. Until NAGPRA, museums were filled with American Indian remains acquired without regard for the feelings and religious beliefs of native people. NAGPRA was passed to redress this history and allow tribes to reclaim their ancestors’ remains and some artifacts. The Smithsonian, under the National Museum of the American Indian Act, and other museums under NAGPRA, have returned (and continue to return) many thousands of remains to tribes. This is being done with the crucial help of anthropologists and archaeologists—including Owsley, who has been instrumental in repatriating remains from the Smithsonian’s collection. But in the case of Kennewick, Owsley argued, there was no evidence of a relationship with any existing tribes. The skeleton lacked physical features characteristic of Native Americans.

In the weeks after the Army engineers announced they would return Kennewick Man to the tribes, Owsley went to work. “I called and others called the corps. They would never return a phone call. I kept expressing an interest in the skeleton to study it—at our expense. All we needed was an afternoon.” Others contacted the corps, including members of Congress, saying the remains should be studied, if only briefly, before reburial. This was what NAGPRA in fact required: The remains had to be studied to determine affiliation. If the bones showed no affiliation with a present-day tribe, NAGPRA didn’t apply.

But the corps indicated it had made up its mind. Owsley began telephoning his colleagues. “I think they’re going to rebury this,” he said, “and if that happens, there’s no going back. It’s gone.”

So Owsley and several of his colleagues found an attorney, Alan Schneider. Schneider contacted the corps and was also rebuffed. Owsley suggested they file a lawsuit and get an injunction. Schneider warned him: “If you’re going to sue the government, you better be in it for the long haul.”

Owsley assembled a group of eight plaintiffs, prominent physical anthropologists and archaeologists connected to leading universities and museums. But no institution wanted anything to do with the lawsuit, which promised to attract negative attention and be hugely expensive. They would have to litigate as private citizens. “These were people,” Schneider said to me later, “who had to be strong enough to stand the heat, knowing that efforts might be made to destroy their careers. And efforts were made.”

When Owsley told his wife, Susan, that he was going to sue the government of the United States, her first response was: “Are we going to lose our home?” He said he didn’t know. “I just felt,” Owsley told me in a recent interview, “this was one of those extremely rare and important discoveries that come once in a lifetime. If we lost it”—he paused. “Unthinkable.”

Working like mad, Schneider and litigating partner Paula Barran filed a lawsuit. With literally hours to go, a judge ordered the corps to hold the bones until the case was resolved.

When word got out that the eight scientists had sued the government, criticism poured in, even from colleagues. The head of the Society for American Archaeology tried to get them to drop the lawsuit. Some felt it would interfere with the relationships they had built with Native American tribes. But the biggest threat came from the Justice Department itself. Its lawyers contacted the Smithsonian Institution warning that Owsley and Stanford might be violating “criminal conflict of interest statutes which prohibit employees of the United States” from making claims against the government.

“I operate on a philosophy,” Owsley told me, “that if they don’t like it, I’m sorry: I’m going to do what I believe in.” He had wrestled in high school and, even though he often lost, he earned the nickname “Scrapper” because he never quit. Stanford, a husky man with a full beard and suspenders, had roped in rodeos in New Mexico and put himself through graduate school by farming alfalfa. They were no pushovers. “The Justice Department squeezed us really, really hard,” Owsley recalled. But both anthropologists refused to withdraw, and the director of the National Museum of Natural History at the time, Robert W. Fri, strongly supported them even over the objections of the Smithsonian’s general counsel. The Justice Department backed off.

Owsley and his group were eventually forced to litigate not just against the corps, but also the Department of the Army, the Department of the Interior and a number of individual government officials. As scientists on modest salaries, they could not begin to afford the astronomical legal bills. Schneider and Barran agreed to work for free, with the faint hope that they might, someday, recover their fees. In order to do that they would have to win the case and prove the government had acted in “bad faith”—a nearly impossible hurdle. The lawsuit dragged on for years. “We never expected them to fight so hard,” Owsley says. Schneider says he once counted 93 government attorneys directly involved in the case or cc’ed on documents.

Meanwhile, the skeleton, which was being held in trust by the corps, first at Battelle and later at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Washington in Seattle, was badly mishandled and stored in “substandard, unsafe conditions,” according to the scientists. In the storage area where the bones were (and are) being kept at the Burke Museum, records show there have been wide swings in temperature and humidity that, the scientists say, have damaged the specimen. When Smithsonian asked about the scientists’ concerns, the corps disputed that the environment is unstable, pointing out that expert conservators and museum personnel say that “gradual changes are to be expected through the seasons and do not adversely affect the collection.”

Somewhere in the move to Battelle, large portions of both femurs disappeared. The FBI launched an investigation, focusing on James Chatters and Floyd Johnson. It even went so far as to give Johnson a lie detector test; after several hours of accusatory questioning, Johnson, disgusted, pulled off the wires and walked out. Years later, the femur bones were found in the county coroner’s office. The mystery of how they got there has never been solved.

The scientists asked the corps for permission to examine the stratigraphy of the site where the skeleton had been found and to look for grave goods. Even as Congress was readying a bill to require the corps to preserve the site, the corps dumped a million pounds of rock and fill over the area for erosion control, ending any chance of research.

I asked Schneider why the corps so adamantly resisted the scientists. He speculated that the corps was involved in tense negotiations with the tribes over a number of thorny issues, including salmon fishing rights along the Columbia River, the tribes’ demand that the corps remove dams and the ongoing, hundred-billion-dollar cleanup of the vastly polluted Hanford nuclear site. Schneider says that a corps archaeologist told him “they weren’t going to let a bag of old bones get in the way of resolving other issues with the tribes.”

Asked about its actions in the Kennewick Man case, the corps told Smithsonian: “The United States acted in accordance with its interpretation of NAGPRA and its concerns about the safety and security of the fragile, ancient human remains.”

Ultimately, the scientists won the lawsuit. The court ruled in 2002 that the bones were not related to any living tribe: thus NAGPRA did not apply. The judge ordered the corps to make the specimen available to the plaintiffs for study. The government appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which in 2004 again ruled resoundingly in favor of the scientists, writing:

because Kennewick Man’s remains are so old and the information about his era is so limited, the record does not permit the Secretary [of the Interior] to conclude reasonably that Kennewick Man shares special and significant genetic or cultural features with presently existing indigenous tribes, people, or cultures.

During the trial, the presiding magistrate judge, John Jelderks, had noted for the record that the corps on multiple occasions misled or deceived the court. He found that the government had indeed acted in “bad faith” and awarded attorney’s fees of $2,379,000 to Schneider and his team.

“At the bare minimum,” Schneider told me, “this lawsuit cost the taxpayers $5 million.”

Owsley and the collaborating scientists presented a plan of study to the corps, which was approved after several years. And so, almost ten years after the skeleton was found, the scientists were given 16 days to examine it. They did so in July of 2005 and February of 2006.

From these studies, presented in superabundant detail in the new book, we now have an idea who Kennewick Man was, how he lived, what he did and where he traveled. We know how he was buried and then came to light. Kennewick Man, Owsley believes, belongs to an ancient population of seafarers who were America’s original settlers. They did not look like Native Americans. The few remains we have of these early people show they had longer, narrower skulls with smaller faces. These mysterious people have long since disappeared.

Leave a comment