By Ryan Saavedra – Nov 2, 2023 DailyWire.com

My cmnt: I’ve included three stories of democrat greed, avarice and stupidity (i.e., Sam Bankman-Fried, Zachary Horwitz, and Bernard “Bernie” L. Madoff) primarily affecting wealthy, commie/socialist-loving Leftists. Democrat politicians from FDR who prolonged the depression by ten years and turned it into The Great Depression, to Jimmy Carter and his double-digit unemployment, interest rates & inflation (his infamous “malaise”) that nearly ruined America, to Barney Frank’s subprime mortgage debacle, to Barack Obama’s Great Recession, and now to the present disaster of Joe Biden – have been spreading war and financial ruin everywhere they go and to everything they touch since their party was founded to protect and promote slavery.

Chk out this link to read more about democrat racism – past, present and future.

My cmnt: In fact the Republican party was created to oppose slavery and the first Republican President, Abraham Lincoln, was so despised by democrats they shot him. Republican Presidents Reagan and Trump, in peace through strength, created some of the greatest economies ever yet were despised, persecuted and rejected by democrats, the media and the Left.

My cmnt: Why do Hollywood-types (all democrats) fall so hard for these phony get-rich-quick schemes perpetrated by other fellow-traveller democrats? Could it have something to do with their worldviews? When you are oriented towards looking at the world in an imaginary way, like children, rather than as it really is, like mature adults, could that also make you susceptible to fantasy financial schemes as well?

My cmnt: What do democrats believe? The universe is eternal and by chance plus time produced the earth and every living thing on it. Man evolved from ape-like ancestors yet strangely is basically good. All evil is a result of societal oppression of the weak (blacks and browns) by the strong (whites) – and this is not because whites are inherently stronger, more industrious and intelligent (which in their Darvinian worldview should be the most likely reason) but rather because they are more aggressive, malicious, greedy and tricksy than the rest. Whites are inherently racist while blacks and browns are all peaceful, loving and generous. In fact whites are so god-like they can even control the weather (now climate) and can make it hotter, colder, wetter, drier, etc. simply by doing white things. Democrats love, revere and worship Mother Earth while they accuse Republicans of hating her and destroying her pristine, eternal environment and replacing her with a male god of domination, malice, and colonization.

My cmnt: Democrats also believe the military and the police are white institutions created to suppress blacks and browns. Women are better than men. In fact they are so magical they can turn into men. Sex is primarily for fun and games and only marginally, if at all, for procreation. In fact sex is so great it is their religion and must be accepted in all its variety and wonder by everyone or you are a bigot. The one evil by-product of uncontrolled sex is not a vast array of devastating, deadly diseases but rather the possibility of producing a baby who therefore must be aborted (killed) to prevent mental anguish in the birther (not mother, remember men too can menstruate). There are at last count 211 different genders. The purpose of life is to eat, drink and be merry and then you die.

Disgraced crypto mogul Sam Bankman-Fried, one of the top donors to the Democrat Party, was convicted on all felony counts Thursday evening in federal court in New York City.

The 31-year-old former billionaire, who founded the FTX cryptocurrency exchange, was convicted following a months long investigation after the company collapsed over night.

He was found guilty of wire fraud on customers of FTX, conspiracy to commit wire fraud on customers of FTX, wire fraud on Alameda Research lenders, conspiracy to commit wire fraud on lenders to Alameda Research, conspiracy to commit securities fraud on investors in FTX, conspiracy to commit commodities fraud on customers of FTX, and conspiracy to commit money laundering.

Bankman-Fried, whose crimes cost victims $10 billion, will go down as one of the biggest fraudsters in history after his company stole their money and used it to fund his lavish lifestyle and political donations.

“We respect the jury’s decision. But we are very disappointed with the result,” said Bankman-Fried attorney Mark Cohen. “Mr. Bankman Fried maintains his innocence and will continue to vigorously fight the charges against him.”

The Washington Post noted that the most damaging testimony against Bankman-Fried came from Bankman-Fried himself after he “traded the chance to tell his side of the story one final time for a gutting cross examination by prosecutor Danielle Sassoon.”

Sassoon grilled him over his own past statements that he made in interviews as he tried to save face following his company’s collapse. He claimed more than 140 times that he could not recall what he previously said.

“This was a pyramid of deceit built by the defendant on a foundation of lies and false promises, all to get money, and eventually it collapsed, leaving countless victims in its wake,” said prosecutor Nicolas Roos. “It’s clear as day the defendant knows that they’re stealing and committing fraud. And that’s exactly what they do.”

This story has been updated to include additional information.

A rising actor, fake HBO deals and one of Hollywood’s most audacious Ponzi schemes

BY MICHAEL FINNEGAN – STAFF WRITER – Los Angeles Times

APRIL 23, 2021 UPDATED 9:40 AM PT

The promise of easy money brought Jim Russell to a bar at the Four Seasons Hotel in Beverly Hills.

Russell, a steel company executive from Las Vegas, had come to meet Zachary Horwitz, a low-level actor seeking investors for his film company.

Horwitz made it sound simple: He would use Russell’s money to buy the rights to cheap movies — “Slasher Party,” “Satanic Panic” and the like — and then resell them to HBO for distribution in Latin America. He’d pay Russell back in six months with a 15% profit.

Russell had already wired Horwitz more than half a million dollars after a friend vouched for the 30-year-old actor.

Now, Horwitz was offering a chance to invest much more.

At dinner that night in 2017, Russell was intrigued but nervous. What would happen if HBO declined to buy the rights to a film, he asked.

“HBO has never backed out,” Horwitz replied, according to Russell.

Over the next two years, Russell and his partners made $80 million in loans to the actor’s company. They thought they were financing scores of deals to buy and sell film rights.

In reality, they’d been lured into what federal investigators describe as one of the most audacious Ponzi schemes in Hollywood history.

Horwitz collected $690 million from investors for movie deals authorities say were fictitious. The HBO and Netflix contracts he used to convince Russell and others that his business was legitimate were forgeries, the government says.

For years, Horwitz kept the con going by using loans from one group of investors to repay what he’d borrowed from another, according to a federal criminal complaint. The investors are now trying to recover $235 million that he never repaid.

The alleged scam opened a money spigot that enabled the actor to live like a studio boss in a lavish Westside home with a screening room, prosecutors say. Horwitz traveled by private jet.

His April 6 arrest on a fraud charge followed a century-old Hollywood tradition of accused swindlers running get-rich-quick schemes that exploit investors’ attraction to the glamour of a movie business they know little about.

Hundreds of emails, text messages and other documents filed in court in Los Angeles and Chicago reveal the vast scale of Horwitz’s operation and show how it ultimately spun out of control. Lawyers for Horwitz, 34, did not respond to requests for comment.

His alleged victims include three of his close friends from college, who roped in parents, grandparents, siblings, in-laws and others, some of whom lost their retirement savings, said Brian Michael, the friends’ attorney.

“It’s been financially catastrophic and emotionally devastating,” he said.

The financial collapse came just as Horwitz’s acting career — under the screen name Zach Avery — was taking off. He starred last year in “Last Moment of Clarity” with Brian Cox, who plays the patriarch Logan Roy on the HBO series “Succession.” He also has a leading role in the upcoming thriller “Gateway,” a feature film with Olivia Munn and Bruce Dern.

Two filmmakers said producers sometimes “attached” Horwitz to a cast regardless of talent.

In a scene from “Trespassers,” a 2018 horror film shot in Malibu, Horwitz writhes on the deck of a swimming pool with a thick dagger plunged into his belly. The director, Orson Oblowitz, was unimpressed by his acting, but he also said he wondered whether the actor’s arrest might bestow “a new cult status” on the movie.

“It’s mind-blowing,” he said. “This dude does not strike me as a criminal mastermind. I am amazed.”

Hundreds of emails, text messages and other documents filed in court in Los Angeles and Chicago reveal the vast scale of Horwitz’s operation and show how it ultimately spun out of control. Lawyers for Horwitz, 34, did not respond to requests for comment.

His alleged victims include three of his close friends from college, who roped in parents, grandparents, siblings, in-laws and others, some of whom lost their retirement savings, said Brian Michael, the friends’ attorney.

“It’s been financially catastrophic and emotionally devastating,” he said.

The financial collapse came just as Horwitz’s acting career — under the screen name Zach Avery — was taking off. He starred last year in “Last Moment of Clarity” with Brian Cox, who plays the patriarch Logan Roy on the HBO series “Succession.” He also has a leading role in the upcoming thriller “Gateway,” a feature film with Olivia Munn and Bruce Dern.

Two filmmakers said producers sometimes “attached” Horwitz to a cast regardless of talent.

In a scene from “Trespassers,” a 2018 horror film shot in Malibu, Horwitz writhes on the deck of a swimming pool with a thick dagger plunged into his belly. The director, Orson Oblowitz, was unimpressed by his acting, but he also said he wondered whether the actor’s arrest might bestow “a new cult status” on the movie.

“It’s mind-blowing,” he said. “This dude does not strike me as a criminal mastermind. I am amazed.”

Horwitz was a psychology major and football jock at Indiana University in Bloomington, Ind., when he befriended fellow undergraduates Jacob Wunderlin, Joseph deAlteris and Matthew Schweinzger. Horwitz stayed close with them after graduating in 2009, attending each of their weddings.

Wunderlin and DeAlteris got finance jobs at J.P. Morgan and settled in Chicago. Schweinzger went to work for Morgan Stanley in New York.

Horwitz also moved to Chicago, where he launched FÜL, a short-lived “fast casual restaurant with a healthy twist,” as he put it.

But Horwitz, who had grown up in Tampa, Fla., and Fort Wayne, Ind., aspired to be a film actor. After two years in Chicago, he and his girlfriend, Mallory Hagedorn, drove to Los Angeles with their Rottweiler, Lucy, for a fresh start.

This dude does not strike me as a criminal mastermind. I am amazed.

— ‘Trespassers’ director Orson Oblowitz

“Feet on the dashboard, cruising with my best friend to a new place to call home,” Hagedorn tweeted on the way to California in January 2012.

They found an apartment in the city’s Miracle Mile neighborhood. Hagedorn enrolled in cosmetology school and became a hair stylist at a West Hollywood salon.

Horwitz hired an acting coach and went on the audition circuit. He had trouble winning parts but made friends with two brothers who helped him break into show business: producer Julio Hallivis and his brother Diego, a director.

With Julio Hallivis, Horwitz co-founded 1inMM Productions, short for One in a Million. It would finance low-budget horror and science fiction films with increasingly prominent roles for “Zach Avery.” Diego Hallivis directed some of them.

In 2013, the company announced a partnership with Miami producer Gustavo Montaudon to distribute films in Latin America. Montaudon was a seasoned player in the field — a former 20th Century Fox vice president who had overseen licensing of the studio’s TV shows in the region.

As Horwitz began soliciting investors, he told them Montaudon and Julio Hallivis were key players in the deals that are now alleged to be fake, according to court papers filed by the government. He called them “principals” in 1inMM Capital, his new film rights company.

Montaudon was responsible for “deal relations” with HBO, Netflix and Sony, Horwitz claimed in a report to investors. He identified Hallivis as chief of the company’s Latin America distribution arm, in charge of content acquisition and relations with foreign sales agents.

Both Montaudon and Hallivis denied participating in the alleged Ponzi scheme.

Montaudon, in a quick phone interview that he cut short, called Horwitz “just a guy I met a long time ago.” “I don’t have a relationship with him,” he said. “I don’t know what he was doing. I have no idea.”

Hallivis’ attorney, Marshall A. Camp, said in an email that the producer was “shocked by the allegations against Zach Horwitz and did not have any role in the criminal scheme alleged.”

The FBI complaint charging Horwitz with wire fraud accused no one else of wrongdoing.

The first college friend Horwitz approached for money was Wunderlin, who — with a partner — lent $37,000 to 1inMM Capital in 2014. Horwitz personally guaranteed the loan and repaid it with interest on time.

Wunderlin and his wife flew to Los Angeles a few months later for the wedding of Horwitz and Hagedorn at the Four Seasons.

Over the next six months, Wunderlin, DeAlteris and Schweinzger got family, friends and associates to join them in lending $1 million more to 1inMM Capital to buy rights to seven movies supposedly licensed to HBO and Sony. Those loans were also promptly repaid, Wunderlin said.

To keep the money flowing, Horwitz talked up his connections. He told his friends that he’d worked for the Seattle venture capital firm Maveron and had financial backing from its co-founders Dan Levitan and Howard Schultz, the former Starbucks chief executive, according to Wunderlin. He claimed Levitan and Schultz had opened doors for him at Netflix, HBO and Sony.

Levitan denied Horwitz worked for Maveron.

“I’ve never met him,” Levitan told The Times. “I’ve never introduced him to anybody.” Schultz could not be reached.

Emboldened by Horwitz’s repayments, the Chicago group formed a company to invest in more movie deals. For five years, the group’s network of “downstream investors” kept growing beyond the original trio, their family and friends. By the end, the Chicago group would put up $490 million in loans.

The deals came with extensive documentation that made them look real.

In one case, the Chicago group lent $1.4 million for Horwitz to buy the rights to an Italian film, “Lucia’s Grace,” and resell them to Netflix for distribution in Chile, Argentina, Brazil and a few dozen other countries. Horwitz promised to repay them $2 million a year later.

Horwitz sent his three friends a 20-page “license agreement” purportedly signed by a Netflix executive to authenticate the deal — a counterfeit, according to prosecutors. How Horwitz obtained model Netflix contracts to copy — with requirements as specific as the minimum screen resolution — is unclear.

Horwitz was sending similar documents to Russell and the others in the Las Vegas group. To them, the Chicago investors’ booming business with Horwitz looked like a threat in the weeks after they met him at the Four Seasons.

Romik Yeghnazary, a Las Vegas home loan officer, told Russell, his friend and tennis partner, that they were competing with people in Chicago for scarce and lucrative film loans.

Yeghnazary — from the start more eager than Russell to lend Horwitz money — said he was trying to “swat those guys away and to get us first right of refusal on all deals that come in.”

In emails full of typos in 2017, Yeghnazary urged his partners to finance deals for four more films — among them a slasher-in-the-woods flick called “Ruin Me.”

“This is the goose that lays the golden egg guys, lets just hope they keep coming month after month,” Yeghnazary wrote, suggesting they “ride this baby out as long as we can.” He brushed off Russell’s annoyance at Horwitz for refusing to let them see his business records.

“If anything not sending us financials proves to me even more that they are not desperate, they don’t need our money,” Yeghnazary wrote.

“It is absolutely ridiculous that he does not want to share his financials as we are currently lending 5mil,” Russell replied. “This is a very common practice to ensure the company is making money, has sales, and has the ability to pay. Sorry, I am not risking millions based upon someone’s word, who I don’t know.”

The next day, Yeghnazary tried to calm his partner. He sent Russell a corporate registration he’d found for 1inMM Capital on the internet.

“Keep in mind please that our HBO contracts we are getting show that they will always have enough money for us, since HBO is sending them the minimum guarantee funds,” he told Russell. “Also keep in mind I verifies those contracts diresctlu with HBO.”

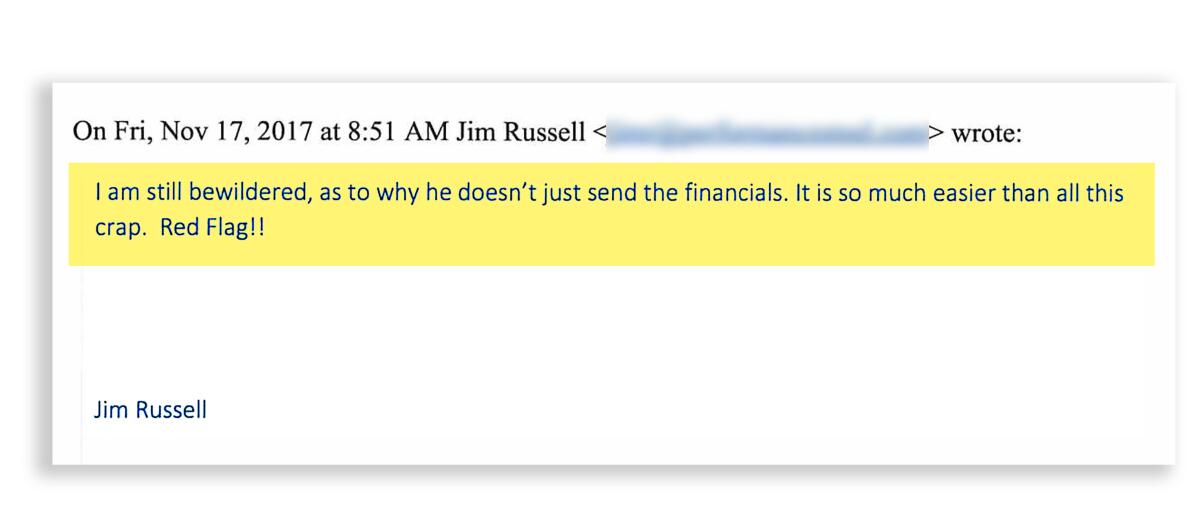

“I am still bewildered, as to why he doesn’t just send the financials,” Russell wrote back. “It is so much easier than all this crap. Red Flag!!”

The Las Vegas group nonetheless kept wiring money to Horwitz.

::

Horwitz abruptly stopped paying back his investors in late 2019; the reason is not yet clear. By then, Horwitz and his wife were well settled with a toddler son in their six-bedroom Beverlywood house with a pool, gym and 1,000-bottle wine cellar. Horwitz liked to play the grand piano.

Their lifestyle had improved dramatically. Horwitz spent $5.7 million on the house, $165,000 on high-end cars, $137,000 on private-jet trips, $125,000 on jaunts to Las Vegas and $55,000 on a luxury watch subscription, the government says. In 2018, his American Express charges hit $1.8 million.

As payment demands and lawsuit threats piled up, Horwitz tried to keep investors at bay by insisting Netflix and HBO were late in paying what they owed. The back-and-forth was detailed in federal court filings by the government.

“Zach, please give us an update,” Russell texted him in March 2020.

He wanted to know whether HBO had set any dates for payment.

“Don’t have any exact info on dates,” Horwitz told him.

Money from HBO was mired in “multiple layers of red tape” due to a corporate merger, Horwitz claimed, but “Gustavo” had been “a huge help.”

“Don’t you think it’s strange that no one’s paying you?” Russell asked.

Horwitz said many HBO vendors, not just 1inMM Capital, were having trouble getting paid. The next day, he refused Russell’s request for a copy of a purported email from HBO. He urged Russell not to contact HBO.

“Not trying to cause any more headaches — just need to be smart about where we are in the process and cannot jeopardize everyone’s deal if HBO decides there has been a confidentiality breach,” Horwitz texted.

Russell told him that “this new hide-the-ball position that you have taken raises a lot of suspicion.”

“There should be absolutely no suspicion,” Horwitz replied, “as I clearly am working diligently to resolve the issue every single day.”

For the rest of 2020, Russell dogged him for payment of $22 million in overdue loans— to no avail.

For the group in Chicago, the stakes were even higher. Not only did they have a bigger portfolio of delinquent loans, but they were also facing payment demands from their “downstream investors.”

Among them was Marty Kaplan, a Chicago finance executive whose family, with partners, stood to lose $10 million.

Kaplan had recently met with DeAlteris — one of Horwitz’s college friends — and discussed the investment risks. DeAlteris told him that “99% of his and his family’s money” was invested in Horwitz’s deals with HBO and Netflix, according to court papers filed by a Kaplan attorney.

“I wouldn’t be able to pay rent if something went wrong,” DeAlteris told Kaplan, according to the attorney.

Once everything started going wrong, the Kaplans were the first investors to sue.

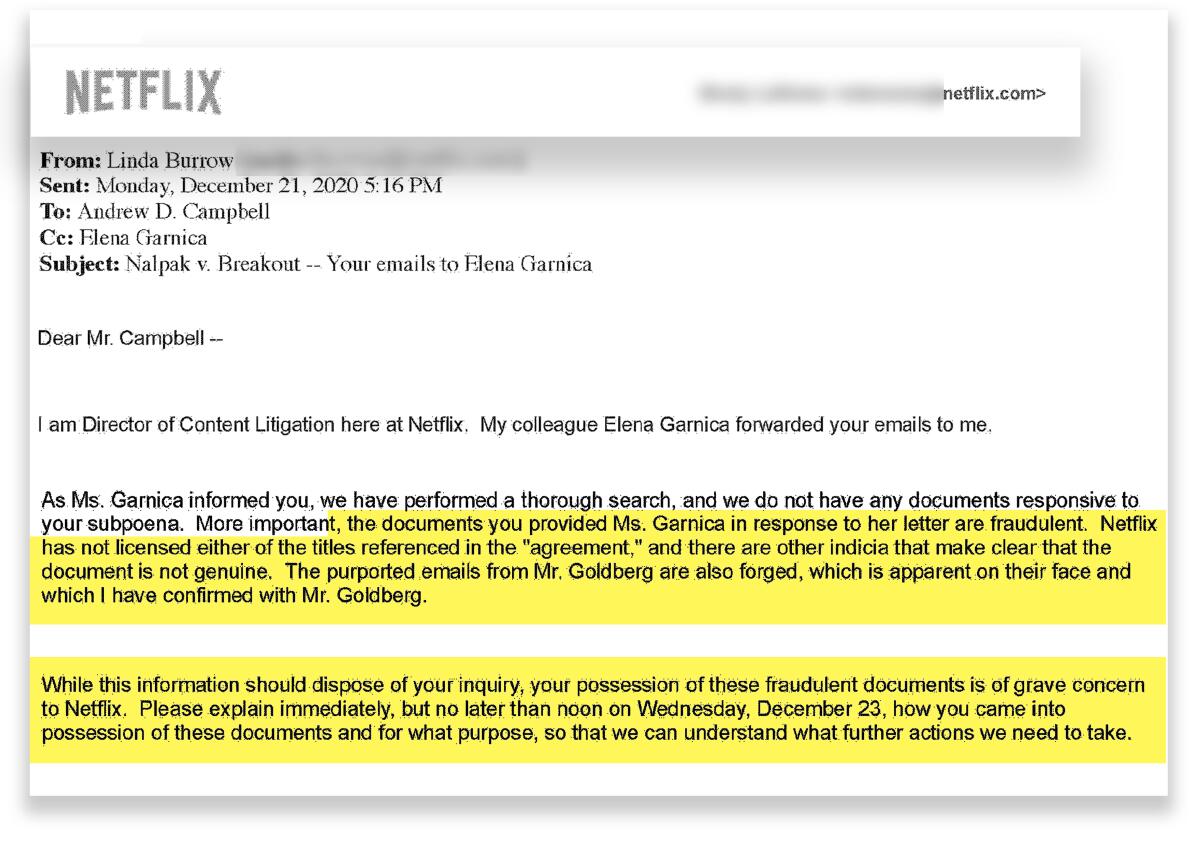

The family’s attorney subpoenaed Netflix in December 2020 for records on its payments to 1inMM Capital for distribution rights on “Tulip Fever” and 18 other movies.

The response was puzzling: Netflix claimed to have no record of doing business with Horwitz’s company, federal court records show.

“While we appreciate your response,” the Kaplans’ lawyer wrote back, “we do not believe that Netflix has performed a reasonably diligent search of its files.”

To prove his point, the lawyer attached a license agreement between Netflix and 1inMM Capital for the documentaries “Active Measures” and “Divide and Conquer: The Story of Roger Ailes.” The next day, he forwarded an email exchange between Horwitz and a Netflix lawyer.

The documents tripped a cascade of alarms. Once the Netflix legal team understood what Horwitz was up to, it was only a matter of time before investors and federal investigators would find out too.

The contract was “fraudulent,” a Netflix attorney told the Kaplans’ lawyer. The email was “forged.”

“While this information should dispose of your inquiry, your possession of these fraudulent documents is of grave concern to Netflix,” she wrote. “Please explain immediately … how you came into possession of these documents and for what purpose, so that we can understand what further actions we need to take.”

With his financial standing deteriorating, Horwitz and his wife put their house on the market in January. The asking price was $6.5 million.

A few weeks later, Netflix sent a cease-and-desist letter to a lawyer for 1inMM Capital, Luke Steinberger of K&L Gates. It demanded that Horwitz stop circulating fabricated Netflix emails and contracts as if they were authentic.

The response was terse. “This is to inform you that K&L Gates is no longer representing 1inMM,” Steinberger wrote.

Horwitz followed up with his own email to Netflix on Feb. 23.

“First and foremost, apologize for any delay in response and the fact that these unfortunate allegations are being discussed at all,” he told the company’s content litigation director. “I am looking into the matter and have informed any/all parties that may have been involved of the situation. Thank you.”

The next day, Irvine businessman Scott Cohen emailed the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission about a feared $15-million loss in “what appears to be a Ponzi scheme” run by Horwitz.

“I have a group of investors that includes around 35 people that have been waiting for nearly 13 months for payment,” Cohen told SEC lawyer Lance Jasper. “People are beyond the point of me managing them and they are really in need of answers.”

The SEC subpoenaed Horwitz that day for his personal financial records and those of 1inMM Capital.

The SEC had been combing through Horwitz’s bank records for weeks. His former Chicago friends had reported him to the FBI and were cooperating in the criminal investigation. They were also threatening to sue Horwitz over $165 million in overdue loans.

Undeterred, Horwitz kept telling them he was working on securing payments from Netflix and HBO. In a March 12 email to Wunderlin, DeAlteris and Schweinzger, he said investors’ accusations of wrongdoing were causing “massive issues for 1inMM and myself personally.”

“I am complying with every single thing that is being asked of me and doing absolutely everything I can to assist, facilitate and explain whatever is needed but right now — it is a problem,” he wrote.

Horwitz’s film company soon lost another marquee law firm. A spokesman for Kendall Brill & Kelly said it severed ties with 1inMM Capital in March, “when we were unable to verify information about several of its purported transactions.”

On April 1, the FBI secured a warrant to track Horwitz’s whereabouts with location data from his mobile phone. Four days later, the FBI got another warrant to search his house for evidence of suspected securities, mail and wire fraud; aggravated identity theft; and money laundering.

FBI agents raided the house, by then in escrow, and arrested Horwitz at dawn the next day.

The SEC got a court order to seize his assets. Its initial look at his bank balances showed his personal account had dwindled to $3,297.

An SEC fraud examiner reported finding four “1inMM” accounts. There was $3,224 in one of them, $306 in another. The third was down to $5. The fourth was empty.

Michael Finnegan is a former Los Angeles Times crime and politics reporter. He covered federal courts in California and state and national election campaigns, including every presidential race from 2000 to 2020. He was previously a City Hall and statehouse reporter at the New York Daily News.

Bernard Madoff, Architect of Largest Ponzi Scheme in History, Is Dead at 82

His enormous fraud left behind a devastating human toll and paper losses totaling $64.8 billion.

Bernie Madoff leaving a Manhattan court in January 2009. The victims of his fraud numbered in the thousands and were scattered from Palm Beach to the Persian Gulf.Credit…Hiroko Masuike/Getty Images

By Diana B. Henriques – Published April 14, 2021Updated April 15, 2021 – The New York Times

Bernard L. Madoff, the onetime senior statesman of Wall Street who in 2008 became the human face of an era of financial misdeeds and missteps for running the largest and possibly most devastating Ponzi scheme in financial history, died on Wednesday in a federal prison hospital in Butner, N.C. He was 82.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons confirmed the death, at the Federal Medical Center, part of the Butner Federal Correctional Complex.

Mr. Madoff, who was serving a 150-year prison sentence, had asked for early release in February 2020, saying in a court filing that he had less than 18 months to live after entering the final stages of kidney disease and that he had been admitted to palliative care.

In phone interviews with The Washington Post at the time, Mr. Madoff expressed remorse for his misdeeds, saying he had “made a terrible mistake.”

“I’m terminally ill,” he said. “There’s no cure for my type of disease. So, you know, I’ve served. I’ve served 11 years already, and, quite frankly, I’ve suffered through it.”

Mr. Madoff’s enormous fraud began among friends, relatives and country club acquaintances in Manhattan and on Long Island — a population that shared his professed interest in Jewish philanthropy — but it ultimately grew to encompass major charities like Hadassah, universities like Tufts and Yeshiva, institutional investors and wealthy families in Europe, Latin America and Asia.

Buttressed by elaborate account statements and a deep reservoir of trust from his investors and regulators, Mr. Madoff steered his fraud scheme safely through a severe recession in the early 1990s, a global financial crisis in 1998 and the anxious aftermath of the terrorist attacks in September 2001. But the financial meltdown that began in the mortgage market in mid-2007 and reached a climax with the failure of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 was his undoing.

Hedge funds and other institutional investors, pressured by demands from their own clients, began to take hundreds of millions of dollars from their Madoff accounts. By December 2008, more than $12 billion had been withdrawn, and little fresh cash was coming in to cover redemptions.

Faced with ruin, Mr. Madoff confessed to his two sons that his supposedly profitable money-management operation was actually “one big lie.” They reported his confession to law enforcement, and the next day, Dec. 11, 2008, he was arrested at his Manhattan penthouse.

The victims of his fraud, some of whom went overnight from comfortable wealth to frantic desperation, numbered in the thousands and were scattered from Palm Beach, Fla., to the Persian Gulf. The paper losses totaled $64.8 billion, including the fictional profits he had credited to customer accounts over at least two decades.

More than money was lost. At least two people, in despair over their losses, died by suicide. A major Madoff investor suffered a fatal heart attack after months of contentious litigation over his role in the scheme. Some investors lost their homes. Others lost the trust and friendship of relatives and friends they had inadvertently steered into harm’s way.

Mr. Madoff was not spared in these tragic aftershocks. His older son, Mark, died by suicide in his Manhattan apartment early on the morning of Dec. 11, 2010, the second anniversary of his father’s arrest. He was characterized by his lawyer, Martin Flumenbaum, as “an innocent victim of his father’s monstrous crime who succumbed to two years of unrelenting pressure from false accusations and innuendo.” One of Mark Madoff’s last messages before his death was to Mr. Flumenbaum: “Nobody wants to believe the truth. Please take care of my family.”

In June 2012, Bernard Madoff’s brother, Peter, a lawyer by training, pleaded guilty to federal tax and securities fraud charges related to his role as the chief compliance officer at his older brother’s firm, but he was not accused of knowingly participating in the Ponzi scheme.

In December 2012, Peter Madoff forfeited all his personal property to the government to compensate his brother’s victims; he was sentenced to a 10-year prison term. And on Sept. 3, 2014, Mr. Madoff’s younger son, Andrew, died of cancer at the age of 48. He had blamed the stress of the scandal for the return of the cancer he had fought off in 2003.

Besides the human toll, professional reputations were destroyed. More than a dozen prominent hedge funds and money managers, including J. Ezra Merkin and the Fairfield Greenwich Group, had to admit that they had forwarded their clients’ money to Mr. Madoff without detecting that he was running a fraud. Swiss private bankers, global commercial banks and major accounting firms were dragged into court by clients who had relied on them to monitor their Madoff investments.

The Securities Investor Protection Corporation, the industry-financed organization set up in 1970 to provide limited protection to brokerage customers, spent more on the Madoff bankruptcy than on all its earlier liquidations combined — and was fiercely attacked by victims, who felt they had been wrongly denied compensation.

And for the Securities and Exchange Commission, which unsuccessfully investigated more than a half-dozen credible tips about Mr. Madoff’s fraud scheme since at least 1992, it was the most humiliating failure in its 75-year history.

The Market Maven

Bernard Lawrence Madoff was born in Brooklyn on April 29, 1938, to Ralph and Sylvia (Muntner) Madoff, both the children of working-class immigrants from Eastern Europe.

He grew up in Laurelton, at the southern edge of Queens near what is now John F. Kennedy International Airport. It was in Laurelton that he met and, in 1959, married Ruth Alpern, whose father had a small but thriving accounting practice in Manhattan.

Before graduating from Hofstra University on Long Island in 1960, Mr. Madoff had already registered his own brokerage firm with the S.E.C., Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities, which he founded partly with money saved from summer lifeguard duty and a lawn-sprinkler installation business that he had run in school.

After an uninspired year in law school, he devoted himself full-time to the business of trading over-the-counter stocks — an enormous market in an era when only the most seasoned American companies could win listings on the New York Stock Exchange and the smaller American Stock Exchange.

His business prospered in the boom years of the 1960s and weathered the downturns of the ’70s by catering to the expanding world of institutional investors, who were rapidly replacing retail investors as the dominant players on Wall Street.

After his brother, Peter, joined the Madoff firm in 1970, it began to build a reputation for harnessing cutting-edge computer technology to the traditional business of trading securities. It was one of the early participants in the fledgling electronic market that ultimately became the modern Nasdaq, and was involved as an investor in several other platforms for computerized trading.

Mr. Madoff’s market leadership and his firm’s willingness to challenge Wall Street traditions made him a trusted adviser as federal regulators struggled to modernize the nation’s marketplace without jeopardizing its international stature. By age 70, he had become an influential spokesman for the traders, the hidden gears of the marketplace.

But it later became clear that he had started engaging in questionable practices soon after he arrived on Wall Street.

Red Flags

By the early 1960s, Mr. Madoff had started accepting money raised for him by his father-in-law, Saul Alpern, and two young accountants who worked in the Alpern firm. At some point the two accountants began to sustain this flow of Madoff-bound cash through the issuance of notes that they failed to register with the S.E.C., as required by law. The commission shut down that hidden money-management business in 1992, after Mr. Madoff had received almost $500 million from the accountants’ clients, who believed he was investing it for them.

Regulators filed civil charges against the two accountants, forcing them to shut down their note-sale operation, but they failed to follow the money beyond Mr. Madoff’s doorstep. And on the S.E.C.’s order, all the money was returned to customers — with cash that Mr. Madoff had taken from one of his largest investor’s accounts, according to testimony in federal court cases related to the fraud.

The regulators later found, however, that most of the money had almost immediately been returned to Mr. Madoff by customers, who had become accustomed to a steady, reliable rate of return on their supposedly conservative Madoff accounts.

By then, hedge funds, pension plans and university endowments were entrusting hundreds of millions of dollars to Mr. Madoff — despite a business operation that was cloaked in secrecy, account statements that were suspiciously antiquated and independent audits that were signed by a one-man firm in a suburban storefront office.

Financial scholars later theorized that Mr. Madoff’s Ponzi scheme lasted so long because it had appealed more to his clients’ fears than to their greed: He promised them consistency in an increasingly volatile market, not eye-popping returns. And he always delivered, never failing to honor a redemption request, and never falling short of the profits he had forecast.

By the 1990s, a cottage industry of hedge funds and private partnerships had grown up to serve as supposedly exclusive portals through which investors could benefit from Mr. Madoff’s investment genius. These funds collected billions of dollars that he used to pay promised profits to his early clients and cover withdrawals when necessary.

Meanwhile, the profits of his legitimate business — which at one time was one of the largest participants in the Nasdaq market — were being squeezed by the same technological advances he had helped bring about. By 2005, prosecutors later said, he was subsidizing his Wall Street firm with money siphoned from his fraud victims.

But there was no sign of distress in the Madoff family lifestyle. While not conspicuously ostentatious by Wall Street standards, the Madoffs lived well. Besides a duplex penthouse on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, they owned a handsome beach house on Long Island, a vintage mansion in Palm Beach and an apartment near the Mediterranean in the south of France; several large powerboats; and a share in a corporate jet.

They were respected philanthropists as well, contributing to cancer research and making major gifts to Yeshiva University, where Mr. Madoff was a trustee and the chairman of the Sy Syms School of Business. He had also served on the boards of several Wall Street organizations, including the National Association of Securities Dealers, now known as Finra.

‘A Legacy of Shame’

Never an effusive man, Mr. Madoff became even more impassive as he and his family were caught up in the media storm that followed his arrest. One tabloid labeled him the most hated man in New York City. On at least one excursion to the courthouse before his guilty plea, a security consultant insisted that he wear a bulletproof vest.

Before being sentenced on June 29, 2009, in a Manhattan federal courtroom packed with spectators and victims, he read from a statement he had prepared with his defense lawyer, Ira Lee Sorkin.

“I am responsible for a great deal of suffering and pain, I understand that,” he told the court. “I live in a tormented state now, knowing of all the pain and suffering that I have created. I have left a legacy of shame, as some of my victims have pointed out, to my family and my grandchildren.”

Mr. Madoff is survived by his wife, Ruth; his brother, Peter; his sister, Sondra M. Wiener; and several grandchildren.

He leaves nothing of his former wealth behind. As part of its criminal case, the government sought more than $170 billion in forfeited assets, a figure that apparently includes all the money that moved through Madoff bank accounts — for whatever purpose — during the years of the fraud.

Both Mr. Madoff’s lawyers and the court-appointed trustee liquidating his firm said that the forfeiture amount included money flowing into the legitimate business operations of the firm as well as the billions paid out to investors as part of the Ponzi scheme. The actual cash losses from his fraud, not counting fictional profits, were most recently estimated at between $17 billion and $20 billion — one of the largest financial frauds on record, and certainly the largest Ponzi scheme ever.

Through the bankruptcy process, some victims were able to recover all or part of the cash principal they invested with Mr. Madoff. Irving Picard, the court appointed trustee who has spent the last decade trying to recoup most of the money for Mr. Madoff’s investors, has, to date, recovered $14.4 billion from lawsuits and settlements — roughly covering all the money investors gave to Mr. Madoff. The recovered sums, of course, do not make up for the billions that investors thought they had made over the years investing with him.

On July 14, 2009, Mr. Madoff began serving his 150-year sentence in a medium-security facility at the Butner correctional complex, about 45 minutes northwest of Raleigh, N.C.

The victims who attended his sentencing in New York had insisted that he should pay for the devastation he had inflicted on those who had trusted him by spending the rest of his life behind bars — and he did.

Maria Cramer and Matthew Goldstein contributed reporting.

Leave a comment